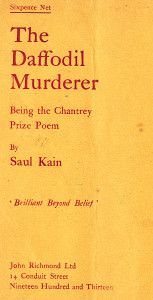

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

[Sassoon (Siegfried)], “Saul Kain”.

The Daffodil Murderer

First edition of the author’s first book not to be privately printed, pseudonymous prefatory note by “William Butler” [the poet/publisher T.W.H.Crosland], original orange-yellow wrappers printed in red, light dust-soiling and rubbing, otherwise very good, housed in an envelope with inscription in Sydney Cockerell’s autograph: “The Daffodil Murderer by Siegfried Sassoon Very Rare”, 8vo, John Richmond Ltd, 1913.

Scarce. Sassoon’s parody of The Everlasting Mercy by John Masefield, apparently written during a moment of tedium, then sent off to Edmund Gosse who in turn forwarded it to Edward Marsh, editor of the Georgian Poetry anthologies. Masefield was as impressed by the work that he hailed the then 26-year-old Sassoon as “one of England’s most brilliant rising stars”. £150

The publisher’s name ‘John Richmond’ was itself a pseudonym for the great contrarian T WH Crosland, whose sardonic introduction, under the name ‘William Butler’ we publish here. It is so far unknown to any digital medium. The Everlasting Mercy, the poem parodied (with some skill) can be found here.

Preface by William Butler.

I have read ‘The Daffodil Murderer’ nineteen times. It is with our doubt the finest literature we have had since Christmas. The fact that it has won the Chantrey Prize for Poetry speaks for itself. Of course, readers of this noble poem will, after wiping their eyes, wish to know something of the personality of the author. I may say at once that he resembles Shakespeare in at least one respect: that is to say, no account of him is yet to be found in ‘Who’s Who’. It is possible that in early life he was a soldier, and fought for his country on many a bloody field; but becoming tired of the military life, he retired to the country on a meagre pension and there interested himself in the rural sights and sounds and bucolic workings of the human bosom which are so admirably portrayed for us in the present pathetic ‘chef d’oeuvre’.

Though a life-long abstainer, Mr. Saul Kain is well acquainted with the insides of various rustic public-houses, and anybody who knows the dear old ‘Barley Mow’, by Langham Lanes, and the genial host and hostess of that quaint hostelry (where the beer is so good and the language so bad) will recognise the fidelity of our poet’s picture of the place. I should also like to say that in an interview which he was lately kind enough to vouchsafe me, Mr. Kain explained that while he has a certain sympathy for murderers, he is no believer in murder as a business. At the same time he thinks that the Poets of our own day have been a little too neglectful of this department of intellectual endeavour and have been too apt to miss it out of their poems. Shakespeare delighted in a real good homicide. As we all know, his tragedies reek with blood and everybody kills everybody else in the last acts. This I submit is as it should be. Mr. Kain confessed to me, however, that he does not really approve of Shakespeare’s methods. He has accordingly made his murderer talk rhyme rather than blank verse, and in order that the severest taste might not be offended the murderer dictates what he has to say to the Prison Chaplain. By this thoughtful expedient a clear flow of unobjectionable language is secured and the reader will doubles appreciate the comfortable result.

I have only to add that Mr. Kain is still a young man, between four and six feet in height, very slim and shy, with eyes which may be blue or brown when you come to examine them closely. He loves poetry better than pipeclay. His War Office pension suffices for his material needs, though the Chantrey Prize of seventy guineas has lately enabled him to augment his dietary with many little extras. He trusts that when this sum is expended he will win another prize. For myself, I think that when the Home Secretary reads ‘The Daffodil Murderer’ (as he undoubtedly will if he has any sense) an effort will be made to secure for Mr. Kain a Civil List allocation of at least 50l. per annum, whereby he may be removed from the poet’s terror which walks in the darkness, namely, the anticipation of hunger, and be at ease to pursue his art for the continued benefit of mankind without fear of the usual consequences. In conclusion, I will say once again that I have read ‘The Daffodil Murderer’ nineteen times, and that on each occasion it made me weep more copiously than I have ever wept before.