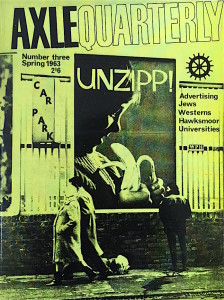

Found in the short-lived early 1960s London cultural magazine Axle Quarterly (Spring 1963) in their column of complaints , rants and broadsides (‘Axle grindings’) this mild attack on the British satirical magazine Private Eye (still going strong with a circulation of 225,000). Axle is almost forgotten, it is occasionally seen being traded for modest sums on eBay, abebooks etc., It survived for 4 issues – contributors included Gavin Millar, Paul R. Joyce, David Benedictus, Michael Wolfers, Paul Overy, Roger Beardwood, Mark Beeson, Ray Gosling, Simon Raven, Tony Tanner, Richard Boston, Melvyn Bragg and Yvor Winters. This piece was anonymous.

Found in the short-lived early 1960s London cultural magazine Axle Quarterly (Spring 1963) in their column of complaints , rants and broadsides (‘Axle grindings’) this mild attack on the British satirical magazine Private Eye (still going strong with a circulation of 225,000). Axle is almost forgotten, it is occasionally seen being traded for modest sums on eBay, abebooks etc., It survived for 4 issues – contributors included Gavin Millar, Paul R. Joyce, David Benedictus, Michael Wolfers, Paul Overy, Roger Beardwood, Mark Beeson, Ray Gosling, Simon Raven, Tony Tanner, Richard Boston, Melvyn Bragg and Yvor Winters. This piece was anonymous.

Millions can’t be wrong aided by The Observer’s unerring flair for pursuing fads of its own creation, Private Eye’s achievement of a 65,000 circulation in just over a year is an interesting phenomenon. This is a figure comparable to that which, say, The Spectator has had to build up gradually over many decades. That Was The Week That Was has been even more successful. It is estimated that it is watched by approximately 11 and a half million people, or nearly a quarter of the population.

First of all why has Private Eye been so successful? It’s easy to read, of course, or rather, easy to skip through. Few read the extended written pieces like Mr. Logue’s boring True Stories. And what most people do read requires about as much effort as a Daily Express cartoon. It’s funnier, and cleverer, and more sophisticated, but all it demands is that one has skimmed the headlines and watched TV occasionally. It doesn’t require any mental effort to take it in (although it may stimulate it).

This is not necessarily a bad thing… There is a very real danger that the New Satire will create a substitute for thinking for the lazy mind. If you can giggle at an important political question or moral dilemma why bother to think about it? Private Eye will provide you with a pat, smart reaction that dispense with thought. It’s much easier to snigger than to think.

It is not a lapse into bad taste that invalidates so much of the New Satire, but its ‘Good Taste’, its complete adoption of the current fashion in cynicism: the refusal to think out a question and commit oneself to a point of view. Good stature is either profoundly reactionary and conservative, or profoundly revolutionary (usually reactionary: Aristophanes, Juvenal, Dryden, Pope, Johnson). The New Satire is neither; the New Satirists seem to have no strongly held values or beliefs. If discernible in their satire. They apparently feel strongly about nothing except their right to laugh at other people’s opinions, beliefs or behaviour.

They might reply that they were not aiming at satire but at lampoon: a virulent or scurrilous attack upon an individual. Here is where the real value of the new satire might lie: in clearing public life of the dreary grey blanket of tact that surrounds it. When Aneurin Bevan called the Tories ‘lower than vermin’ his colleagues emitted horrified gasps; his opponents and the Press bloodthirsty howls. It just wasn’t cricket (or politics – the two had become indistinguishable). Yet Bevan’s remark was in a great parliamentary tradition wherein Churchill at the start of his career had referred to the Liberals as ‘black toads’ and Gladstone and Disraeli had heaped obscene insults on each others’ heads across the floor of the House of Commons. This sort of public slanging match is considered indecent in the polite bourgeois world of the Welfare State.

What is lacking today is an essential dichotomy between public and private life. There used to be an understood convention that men could say the most scandalous things about each other in public and yet often remain on friendly, or at least polite, terms when they met in private. This convention was good because it separated a man’s professional from his personal life. Nowadays if a man’s professional integrity or competence is questioned he considers it s slight not only on his professional capacity but also on himself as a private individual. Strict enforcement of the libel laws has increased this touchiness about public comment on public persons. If Private Eye is likely to stimulate a return to less tactful and hypocritical public life it is doing a useful job. But is it? It lacks real savagery. Compare it with what was being produced in Germany in the twenties, with the plays of Brecht to the drawings of George Grocz. Beside these Private Eye seems what it is, a clever Oxbridge prank. Even its back page figures lampoon on well-known public figures says no more than is said at bitchy cocktail parties.

The pleasant shock of surprise is only in seeing what we all think and say in private made public in print. The same goes for That Was The Week That Was except that it is less barbed, not so funny and its joke far too extended…

Finally, satire that appeals to 11 and a half million people cannot be satire; satire must shock and outrage: it can only have a minority audience, for it must discredit and spit upon the values and aspirations of the age.

Without reading the copies of Private Eye on which the critic bases his judgement it is hard to assess the validity of the views expressed, but one word is entirely missing from this piece—-irony. The majority of the satire produced by the present day Eye is based on irony, which remains the most sophisticated and destructive type of satire, as Swift showed 3 centuries ago. The rest of the satire in the modern Eye is created by parody–usually the work of our greatest living parodist, Craig Brown.

It would be interesting to compare copies of the 1964 Eye with those from the last 20 years. Such an exercise would , I think, reveal how far what lazy journalists still call ‘ Oxbridge ‘ satire has come since 1964, especially in really inventive irony and brilliantly accurate parody. Incidentally, Craig Brown didn’t even attend Oxbridge, but, I think studied drama at Bristol.