Found- an anonymous article in Pearson’s Magazine (London 1898) on the artist and Royal Academician Arthur Hacker. Of note because there is not much about him – a short Wikipedia entry and this piece from Art Magick. He mainly painted genre and historical scenes,mythological and allegorical subjects (some verging on kitsch) and for the middle part of his career was a successful portrait painter. He studied in Paris under Leon Bonnet, renowned portrait painter and life long friend of Degas. The article, chatty and light in tone, sees the artist in his successful mid career.

Pictures and their Painter – Arthur Hacker

Born in London in 1858, Arthur Hacker. became a student at the Royal Academy when he was seventeen.. As Millais said when he presided for

the first and only time at the annual banquet, so soon to be followed by his death: “I received here a free education as an artist – an advantage many a lad may enjoy who can pass a qualifying examination, and I owe the Academy a debt of gratitude I can never repay.” The qualifying examination is a full-length drawing from a Greek statue carefully shaded, with another drawing showing the anatomy of the figure. It is a matter of three or four month’s hard grind, and brings out the faculty for taking pains, for not only has the drawing to be very accurate, but the modelling must be intelligently and delicately rendered, and to do this the drawing must be stippled very finely, a trick which can only be acquired by practice.

Many clever students have had to try two and even three times before they have sent in a drawing acceptable to the Academician. Arthur Hacker was successful at the first attempt.

Many clever students have had to try two and even three times before they have sent in a drawing acceptable to the Academician. Arthur Hacker was successful at the first attempt.

He was a student at a time when attention was directed to the training given in the Paris studios, and thither he went at the end of the three years spent in the Academy Schools to the atelier Bonnat, where he worked hard for two years. And students do work hard in Paris, for they begin at eight in the morning, working to twelve. Then comes the breakfast-lunch, which is taken in some cheap cafe, where you get four or five course for a franc, including a glass of vin ordinaire.

Work goes on again from two till five, and again in the evening, and though there are students’ balls and parties, and outings to Fontainebleau, a Paris studentship is a time of unremitting hard work, with the added problem of making both ends meet.

Many a student has starved in an apartment at the top of one of those large houses which in Paris house so many families, in order to take advantage of the training offered by the Beaux Arts or Julien’s, and though, when you look back upon those days from the standpoint of success they seem bathed in the colour of romance, the hard work, neglect, poverty, and unsatisfied longing of frustrated ambition is bitter indeed at the time.

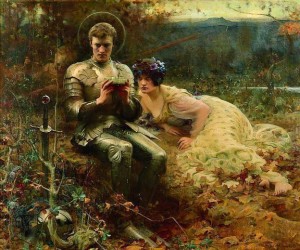

Mr. Hacker has lived to work out some of the ideas which came to him doubtless in his student days, and from dreaming of fame to winning the guerdon the time had been very short, for at the early age of thirty-five the Academy elected him to an Associateship; and, furthermore, two years ago purchased his large picture (now in the Tate Gallery) under the terms of the Chantrey Bequest. Between two and three thousand pounds is spent annually in pictures and sculpture, interest on the money left to the Academy by the sculptor, Sir Francis Chantrey.

Mr. Hacker is much sought after for portraits, and this year’s Academy will see no subject-picture from his hands. We shall give in a subsequent number a reproduction of his most charming portrait of that clever artists, Miss Ethel Wright. This picture hangs in Mr. Hacker’s studio. The sitter gave him as many as fifty sittings, and the result is that the portrait has subtle charm about it which is not always found in all great portraits.

Mr. Hacker ought to be a happy man, for he has found customers for all his important pictures, and this is a great stimulus to ever increasing effort. It takes away one’s belief in oneself to find one’s work returning time after time to adorn the studio walls or little the place, the frames having been used for newer works. The painter who can make a collection of his own pictures, as did Corot and our own Linnell, must have an abundance of belief in himself, for painting for posterity is a poor business. Recognition is so stimulating.