J. H. Slater, a lawyer by training, who became the doyen of late Victorian writers on rare books, deserves to be far better known than he is. It is scandalous, for instance, that someone with so much influence and practical discernment has no Wikipedia page ). He often comes across as a grumpy, somewhat world-weary and cynical guide to the world he knew so well. Though occasionally inspirational ( particularly on incunabula ), his observations on the second hand book trade in general were often shocking when he made them, and continue to be distressing to many collectors today. Take some of the comments in his chapter entitled ‘ books to buy ‘.

‘ Few collectors, who are not specialists, care very much for the utility of their libraries; in many cases, indeed, it is not a question of utility at all, but of extent, though I apprehend that no one would wish to crowd his shelves with rubbish merely for the sake of filling them. As an immense proportion of the books which have been published during the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries clearly come under that category, the collector has much to avoid, and stands in need of considerable experience to enable him to make a selection…’

Such a statement might be regarded as sacrilegious to many collectors who feel that any writing that has reached the stage of publication must, ipso facto, be worthy of respect. The fact that a book printed in the sixteenth century has survived into the twenty-first doesn’t mean that it is worth collecting. The often argument that such a book reflects the morals, taste or intellectual climate of the time is not a valid one. Discernment must be another factor and that can only be acquired through knowledge and scholarship, or ‘experience ‘,as Slater goes on to argue.

Slater cites the example of Naude, the seventeenth century bibliophile whose method of purchasing, was ‘ if not unique, was at any rate, uncommon’.

‘His favourite plan was to buy up entire libraries, and sort them at his leisure; or when these were not available in the bulk , he would, as Rossi relates, enter a shop with a yard measure in his hand, and buy his books by the ell. Wherever he went, paper and print became scarce: ‘ “ the stalls he encounters were like the towns through which Attila had swept with ruin in his train”

Then there was the notorious bibliomaniac Rev. Richard Heber (1773 – 1833 whose great wealth was spent on a vast library that occupied eight houses in Britain and the Continent. His dictum was ‘ no gentleman can be without three copies of a book, one for show, one for use and one for borrowers ‘. In 1834, after his death, the sale of his books occupied 202 days, and in the words of Slater, ‘ flooded the market with rubbish —a worthy termination to a life of sweeping and gigantic purchases, made in the hope of acquiring single grains of wheat among his tons of worthless chaff’.

Continue reading

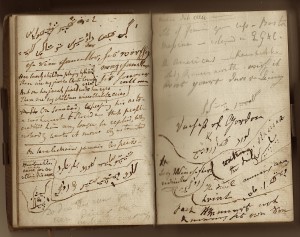

The front part is a short record of travels in Germany and Belgium in which the anonymous male diarist, who is accompanying his mother, at one point tells us that he was born in 1802, is very scathing about the appearance of most of his travelling companions. In one instance he remarks that the young son of the parson in the party ‘seemed to be as ugly as his father and as vulgar as his cousin’. He is singularly unimpressed by most of the foreigners he encounters along the way. For instance, he notes that his fellow diners at the Table d’Hote, were ‘12 disgusting looking Germans who luckily eat enormously & spoke little ‘. The following evening diners at the same table were’ rather more disgusting in their appearance & manner of eating than the day before ‘. Predictably, he is also critical of the meals he is obliged to eat and the inns that serve and accommodate him. In one inn he accuses the landlord of serving him a dish of greyhound puppy. Our diarist certainly places himself above the common lot. He seems knowledgeable about art and is a little snooty regarding the collections he views, suspecting that most of the paintings were copies from the masters. More positively, he is often ecstatic about the scenery and buildings he encounters and he particularly praises cathedrals and castles. We yearn for more, but unfortunately, the diary stops abruptly after thirty pages.

The front part is a short record of travels in Germany and Belgium in which the anonymous male diarist, who is accompanying his mother, at one point tells us that he was born in 1802, is very scathing about the appearance of most of his travelling companions. In one instance he remarks that the young son of the parson in the party ‘seemed to be as ugly as his father and as vulgar as his cousin’. He is singularly unimpressed by most of the foreigners he encounters along the way. For instance, he notes that his fellow diners at the Table d’Hote, were ‘12 disgusting looking Germans who luckily eat enormously & spoke little ‘. The following evening diners at the same table were’ rather more disgusting in their appearance & manner of eating than the day before ‘. Predictably, he is also critical of the meals he is obliged to eat and the inns that serve and accommodate him. In one inn he accuses the landlord of serving him a dish of greyhound puppy. Our diarist certainly places himself above the common lot. He seems knowledgeable about art and is a little snooty regarding the collections he views, suspecting that most of the paintings were copies from the masters. More positively, he is often ecstatic about the scenery and buildings he encounters and he particularly praises cathedrals and castles. We yearn for more, but unfortunately, the diary stops abruptly after thirty pages.