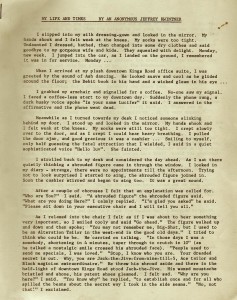

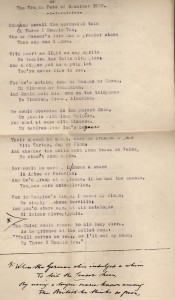

Found in a copy of Montague Summers’ Restoration Theatre is this typed copy of a poem entitled ‘The Dutch Mail or The Tragic Fate of Examiner 3X22.’ It is dated February 27th 1918 and signed E. de K, which suggests that it is an original composition. The corrections in black ink bear this out. It is most likely to have been sent to a magazine editor.

Found in a copy of Montague Summers’ Restoration Theatre is this typed copy of a poem entitled ‘The Dutch Mail or The Tragic Fate of Examiner 3X22.’ It is dated February 27th 1918 and signed E. de K, which suggests that it is an original composition. The corrections in black ink bear this out. It is most likely to have been sent to a magazine editor.

It tells the story of a polyglot censor named Examiner 3X22 whose job it was to censor outgoing mail during the First World War. Though happy to be dealing with mail written in many languages, he is forced to admit one day that he couldn’t read Dutch. He quickly remedies this defect until he becomes so fluent in the language that he is mistaken for a native. Unfortunately, his mastery means that he is now forced to censor ‘stacks’ of letters from the Dutch East Indies. The cumulative effect on the censor of dealing with these ‘verbose effusions vapid’ results in a rapid decline. One day he faints from the effort, falls from his chair onto the floor where he rapidly expires.

This is obviously a squib, possibly ridiculing both the Dutch language and in particular employees of the Dutch East Indies Company whose language it was . On the surface Examiner 3X22 seems to be working for the Netherlands government, but this cannot be so if he is unable to read Dutch. On the other hand, if he is working in Britain, how is it that so much mail from the Dutch East Indies is being censored in Britain? A possible alternative to either of these scenarios is that the censor is working in South Africa, which during the First World War was a self-governing dominion of the British Empire and as such contributed troops to the war effort in Europe and suffered many losses. The writer’s surname de Koch/ Koch/Klerk was a common enough one in South Africa, which had been colonised by the Dutch as well as the British. In addition, an online postal history site records a letter sent to Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies (now known as Indonesia), being censored in 1915.

The squib may have political undertones. After all, the Boer War was a recent memory for both the defeated Boers and those of British heritage, though the exact nature of the tensions in South Africa that prompted the satire remain to be discovered. We welcome comments from the Jottosphere on this issue. [R.M.Healey]