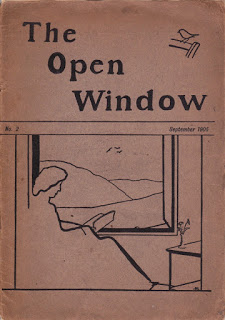

One thing that could be said of the special Christmas 1930 edition of the literary review The Bookman is that it was sumptuous, and due to its inclusion of art paper, very physically if not intellectually, heavy. Always unashamedly middlebrow in character, a fact borne out by the lack a proper appreciation of D. H. Lawrence, who had died a few months earlier.In fact, the only critique of him focused almost solely on his character, where he is dismissed as a ‘puritan’, rather than the originality of his writings. While other more serious literary journals had given Lawrence the respect he deserved, and the Times had trashed him, the Bookman, devoted more room to reviews of adventure stories for children , modern novels of manners, travelogues and popular histories than it did for serious fiction and poetry. In many ways it was the sort of magazine read by those who took the Yorkshire Post, the Morning Post and the Daily Telegraph. It comes as no surprise that the last two newspapers took full page adverts puffing their book pages. It is indicative of the conservatism of the Yorkshire Post that Geoffrey Grigson, then a junior staffer there, had to exert great pressure on its London Editor to insert a brief notice on Lawrence, a writer of whom, Grigson remarks, his boss had probably never heard.

By December 1930, the recently married Grigson, then aged 25, was keen to supplement his exigent pay as a junior, and so in the year in which John Masefield had been appointed the successor to Robert Bridges as Poet Laureate, he chose The Bookman for an assessment of past Poet Laureates ( his Editor doesn’t seem to have minded this moonlighting). Perhaps another indication that he was keen to make his debut as a serious writer, rather than a hack, was the fact that around this time he placed an advert in the TLS asking if anyone who had material relating to the eighteenth century satirist ‘ Peter Pindar’ ( aka John Wolcot, to get in touch with him, as he was writing a biography. He had managed to obtain a Reader’s Card for the British Museum, perhaps to gain access to books by Wolcot. Continue reading