We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

What is far more reprehensible, however, is the sense of betrayal felt by someone who having taken into their home a friend, colleague or relation down on their luck, discovers that this lodger has been stealing books from their shelves to sell to book dealers. This wouldn’t have happened to the impoverished young Ransome, of course, but it did happen to the comparatively well-off Geoffrey Grigson while editor of New Verse.Grigson, like Ransome in his time, would’ve been sent dozens of books to review each week, most of which he would have sold to second hand booksellers. Other books for review he would have kept for his own collection, particularly those published by fellow poets he particularly admired, such as Auden, MacNeice and Wyndham Lewis. Grigson also held regular parties for his New Versecontributors at his home in Keats Grove, and it is more than likely that on these occasions he would have asked some of his guests to sign the review copies he had retained for his own use. It is equally, likely, of course, that a grateful guest would have presented a signed copy of his book to Grigson.

Whatever the circumstances, Grigson must have assembled a decent collection of books, including ‘modern firsts’ at Keats Grove. And it was at Keats Grove that Grigson and his American wife Frances first met the young Ruthven Todd, ‘an unemployable, persistent, rather squalid-looking tall, grey oddity ‘ who wrote poetry and turned out to be a book thief. At one point he actually showed Grigson a copy of MacNeice’s Blind Fireworksinscribed by the poet to his wife. This could only have come from the library of MacNeice himself. Anyway, a few years later Grigson and his wife moved to Wildwood Terrace, not far from the Old Bush and Bush, and it was here that Todd turned up again, this time to take up the offer of bed and board for 10 shillings a week. Unfortunately, Todd couldn’t even afford this negligible sum, so he took to stealing from Grigson’s bookshelves. The whole sorry story, as Grigson tells it in Recollections,is distinctly farcical:

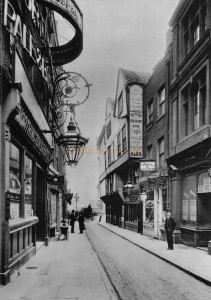

‘…a bookseller whose shop I frequented in Cecil Court..…told me he had just bought ten shillings’ worth of books in one of which was a letter addressed to me. I was in that shop again some weeks later: the bookseller had bought more books—always ten shillings’ worth or thereabouts—from the same seller, in one of which this time was my signature, and the seller was—Ruthven Todd. Between us we kept the arrangement going for some time. Ruthven bought the books to Cecil Court, the bookseller paid him the required ten shillings. Ruthven with scrupulous regularity paid the ten shillings to me wife, and I went down to Cecil Court, and retrieved the books, for ten shillings… We never taxed the Innocent Thief with his theft, this generous creature who seldom came to see us without some present, paid for God knows how, for the children . Continue reading