‘I have found another way… ‘So wrote fantasy novelist Edith Allonby (1875 – 1905) in a note  found on her lap following her suicide, aged just thirty, in December 1905. When discovered she was sitting in a comfortable chair dressed in a silk evening gown with fresh flowers in her hair. By her side was an empty bottle of phenol (carbolic acid), the poison of choice (bleach was another) for many suicides in the UK at that time, due to its availability and quick, but painful, action.

found on her lap following her suicide, aged just thirty, in December 1905. When discovered she was sitting in a comfortable chair dressed in a silk evening gown with fresh flowers in her hair. By her side was an empty bottle of phenol (carbolic acid), the poison of choice (bleach was another) for many suicides in the UK at that time, due to its availability and quick, but painful, action.

For Allonby, a schoolmistress from Cartmel, Lancashire whose two previous works of ‘ satirical fantasy ‘, Jewel Sowers (1903) and Marigold

(1905), both set on the imaginary planet of Lucifram, had not sold well, there seemed little choice. In her suicide note she explained that after four years of labour on her latest book , a spiritual fantasy about life and death that she claimed had been given to her by God, her publisher Greening had rejected the manuscript, as had other publishers. ‘I have tried in vain ‘, she wrote,’ …yet shall The Fulfilment reach the people to whom I appeal, for I have found another way…’

That way was an act that would make her posthumous book a sensation at the time, for Greening did change their minds about its publication once the author was dead. It came out in a limited edition, which makes it and her previous two novels, scarce and valuable items today. It is possible that originally all the publishers to whom it was shown simply found the subject matter of The Fulfilmenttoo difficult to deal with. The author herself admitted that her book contained ‘either truth or page upon page of blasphemy ‘. Today, we are more open minded on spiritual matters. [R.M.Healey]

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

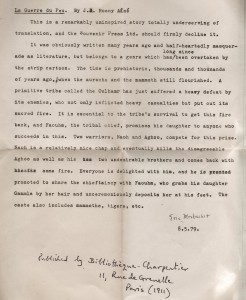

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

Found – the typescript of a review by

Found – the typescript of a review by