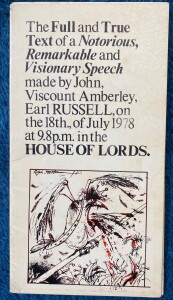

Found – a small folding pamphlet illustrated by Ralph Steadman and published in London by  Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p. It has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords. John Conrad Russell was the son of Bertrand Russell. After the speech he left the House of Lords and was prevented from re-entering it by ushers. It is said to be the only speech given in the Lords that is not fully recorded by Hansard. His poposal to give three quarters of the nation’s wealth to teenage girls had some coverage in the papers the next day, but the speech is rather forgotten (until now). Here is the first part. More to follow.

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p. It has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords. John Conrad Russell was the son of Bertrand Russell. After the speech he left the House of Lords and was prevented from re-entering it by ushers. It is said to be the only speech given in the Lords that is not fully recorded by Hansard. His poposal to give three quarters of the nation’s wealth to teenage girls had some coverage in the papers the next day, but the speech is rather forgotten (until now). Here is the first part. More to follow.

My Lords, I rise to raise the question of penal law and lawbreakers as such and question whether a modern society is wise to speak in terms of lawbreakers at all. A modern nation looks after everybody and never punishes them. If it has a police force at all, the police force is the Salvation Army and gives hungry and thirsty people cups of tea. If a man takes diamonds from a shop in Hatton Garden, you simply give him another bag of diamonds to take with him. I am not joking. Such is the proper social order for modern Western Europe, and all prisons ought to be abolished throughout its territories. Of course the Soviet Union and the United States could include themselves in these reforms too. Kindness and helping people is better than punitiveness and punishing them, a constructive endeavour is better than a destructive spirit. If anybody is in need, you help him, you do not punish him. Putting children into care and other forms of spiritual disinheritance ought to be stopped. Borstal ought to be stopped and the workings of the Mental Health Act which empowers seizure of people by the police when they are acting in a way likely be harmful to themselves or others or to be looked into.

What are you? Soulless robots? Schoolmasters who are harsh with schoolboys who later as a result burn down the schoolhouse ought to be more human. Schoolboys in any case are present treated with indescribable severity which crushes their spirits and leaves them unnourished. The police ought to be totally prevented from ever molesting young people at all or ever putting them into jails and raping them, and putting them into brothels or sending them out to serve other people sexually against their wills.

The spirit ought to be left free, and chaining it has injured the creative power of the nation. The young unemployed are not in any way to have become separate from governmental power, but ought to have been given enough to live on out of the national wealth to look after themselves and never ask themselves even to think of working while there is no work to be had. Continue reading