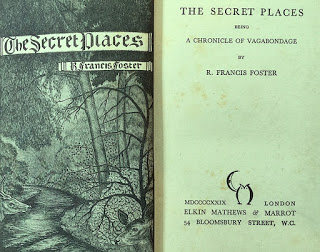

Two more chapters of The Secret Places (Elkin Mathews & Marrot London 1929) - a chronicle of the 'pilgrimages' of the author, Reginald Francis Foster (1896-1975), and his friend 'Longshanks' idly rambling in Sussex, Kent and Surrey. See our posting of the first chapters for more on Foster and this book, including a contemporary review in The Tablet.

XI

THE FRIARY IN THE HILLS

It chanced that I had to go over into Surrey hm Sussex to pay a visit to the Franciscan Friary whence we had started on our wanderings. Leaving Longshanks, therefore, in an inn at Chidding in the fold country, whither we had gone in search of a man who claimed to be a direct descendant of Earl Godwin–though what he was doing here in the south I do not know–I went through the gap in the hills to Guildford and, being weary, took a ‘bus thence to Chilworth.

Because I was stupid with sleep I left that ‘bus at the wrong place, and, being unfamiliar with the country west of the Friary, I sought direction from a butcher and a queer man who carried a lighted lantern, though it was yet mid-afternoon. Thereafter I walked two miles, as I had been told, I came at last to a large crucifix by the roadside and entered the Friary grounds.

All day a blustering wind from a little south westward had swept the country and brought rain; now the air was still. I climbed the rough drive. The tang of wood-smoke and dying fern made the air sweet and homely, and through the trees I could see the Friary's thin spire. The crunch of my boots on stones made the only sound in that stillness.

In the wide stone doorway I pulled at a great chain, and a bell clamoured. In a little while came a lay brother, brown-habited, who was apparently a new-comer there, for he did not recognise me. He gave me a welcoming smile and invited me inside. I asked if I might see the Father Guardian, and the lay brother took me into the plain room which I knew to be the parlor. And there I waited until I heard the creak of the Father Guardian’s sandals. For only Superiors have sandals that creak. It is a kindly warning of their approach.

A simple man is the Father Guardian of that place, with a richness in his voice that speaks of Ireland. I have spoken of him before, and he cannot but be remembered.

For what purpose I had journeyed through the gap of Guildford from Sussex back to our starting-point does not matter. I did what I had in mind, and afterwards the Father Guardian took me into the refectory and gave me strong tea from a metal tea-pot and a slab of brown bread with delicious butter that rather increased than satisfied my hunger. And then, since he would have it so and I was so desirous, I told him of all that had befallen Longshanks and myself since he gave us his kindly blessing.

Afterwards we went out into the trim garden, which is so sandy that much work is needed before anything will grow, and a fox-terrier, seeing me, leapt forward and barked shrilly; then he saw my brown-clad companion, and, whining affectionately, received me as a friend–for I had not met him on my previous visit. The three of us, the Superior, the dog and I, went through the wood where the friars take their exercise and where, the Father Guardian told me, nightingales sing in the Spring (but now it was filled with the melancholy stillness of late Autumn), and so completed a rough circle, passing a monk who bears a famous name and who was scything dead bracken, and coming finally to a green patch where young novices, garbed in their brown habits, played a foursome of tennis.

In the wide doorway, where later I bade my kindly host farewell, we lingered awhile and looked across to the opposite hill on which stands St. Martha’s Chapel, and whither Longshanks and I had gone when we started our aimless pilgrimage. The silence stilled our tongues, but presently the monk told me that it was not always so quiet there–as I knew, but I did not say so.

“In the summer,” he said, “cars come up the road below us, and there is no silence then. Yet only a little while back no one ever came off the Dorking–Guildford road,”

I asked him what had cause the change. He shook his head.

“I’ve no memory of her name,” he said, “but it was a woman who brought disquiet here.” He pointed across the valley to where Newland’s Corner lies. “They were content to stay up there and admire the view,” he said, “until she got lost on the Downs one night and they beat all round the woods to find her. It was she who brought the curious here.”

I pondered on that as, afterwards, I walked down the rough road to Chilworth station; but not for long. For twilight was falling and St. Martha’s Chapel on the height was outlined against the green light of a fading sky. A dog barked down in the valley; there was no other sound. I thought comfortably of Longshanks and the warmth of his inn.

XII

THE CAVE OF SILENCE

Someone suggested–or perhaps I misunderstood him–that the lineal descendant of Earl Godwin, whom I mentioned earlier, is a myth. That stirred Longshanks to great anger. He said that while I went on my pious errand through the gap of Guildford to Chilworth and left him at the inn at Chidding, he had actually found his man and had drunk with him from the same great pewter, which proves that he exists. Longshanks also made a song about him, but I shall not give its twenty-three verses here, nor any of the.

Longshanks bade tryst with me at that inn, and when I came into Sussex from the north we went adventuring in the fold country. Thereafter we pressed southward through Petworth, whose church spire slants when you cock your head and look at it, down Byworth’s cobbled street, and so to the hills where, in a little while, we resolved that our journeying should have aim. It was then that we chanced upon the Poet–of whom more hereafter–and we spent most of that day with him in a barn, taking shelter from a furious rain.

He told us how he would reform the world, and particularly Sussex, and then he inveighed against Lord Birkenhead, Mr. Kipling, William Rufus, and Commander Kenworthy. When we stopped him he asked us if we had seen the Cave of Adullam hard by, and because we had not he took us out into the mud and brought us to the foot of a hill near which, to the north, there is a windmill, a farmhouse, four cottages, a signpost with one arm which points to Chichester, and an inn where once William Cobbett quarrelled with his host–a surly man. Now that I have described the place you cannot fail to find it.

As we climbed the hill the Poet told us very wordily that the Cave of Adullam had been the stronghold of Leofwine, the brother of King Harold, who, wrongly supposed to have been killed, escaped after the Battle of Hastings. He gathered together some of the Saxon survivors, and lived there, David-like, as an outlaw with his band, defying Duke William, who, not being a Sussex man either by birth or adoption (as many people are), failed utterly to find that place.

“And,” said the Poet, “I have lately seen a man, called Alfred Leffin, or some such name, who is said to be the twenty-fifth descendant in a direct line from Leofwine, the son of Godwin. He lives–“

“–up in the fold country,” said Longshanks, and the Poet looked annoyed that his tale had thus been spoilt.

Was there ever such a strange coincidence? All the pother about Godwin’s descendant was settled as soon, almost, as it was started.

We found the cave set in a chalk hollow cut in the hill. The Poet said that none of the fifty-odd folk who live near enough to deem the place part of their territory would enter it, for it was haunted. And indeed it is an awesome place. The rain had stopped as we made our way thither, and the Autumn sun shone warmly, but in the chalk hollow the light was grey and the air chill. We peered into the cave and later entered it, superstitiously fearful. It narrowed to a tunnel, which went downwards.

“You would say that there would be a wonderful echo in such a place,” said the Poet softly. “Shout and listen.”

And Longshanks threw a mighty shout into the tunnel. There was no echo; not even the faint rumor of sound that follows a cry in the open. Utter silence clipped off the shout, and Longshanks and I were too startled to move and break it.

Then Longshanks pulledd himself together and, peering in the tunnel, shouted again. But the result was the same. I tried, making my voice linger. The tunnel swallowed the cry whole and breathed none of it back.

It was unnatural. We came back into the cave, Longshanks and I, to find that the Poet had gone. Nor could we find him when we stumbled outside. But we heard someone singing, and presently a figure stood against the skyline above the hollow. It was the Poet. He waved to us and then disappeared. For some time we heard his singing. When that died there was not even a murmur of wind to break the silence, and the grey light was like a mist.