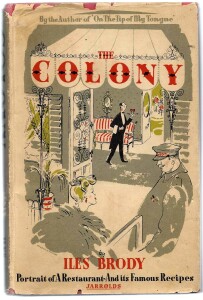

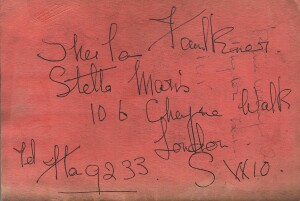

We don’t know whether the Australian actor and flamenco dancer Trader Faulkner ( 1927 – 2020) acquired a copy of The Good Time Guide to London not long after he arrived in London from his home in 1950, probably accompanied by his mother Sheila, a former ballerina. But we do know that the couple moved into a houseboat named ‘” Stella Maris “moored off 160, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, sometime in the early fifties. The Guide, which was specifically aimed at foreigners new to the metropolis, had a section on Chelsea.

‘…this is Chelsea, undisputed artists’ quarter of London. You can wear what you please, and nobody will give a damn. Though the painters and the designers, the ballet dancers and the actors ( my italics) may be outnumbered by the sober citizens, it is their spirit which dominates. Without it, Chelsea would lose the greatest part of its attraction…Cheyne Walk and Cheyne Row is where many an ambitious London dreams of buying a house some day…’

The same Guide also featured a section on ‘Ballet ‘, most of the contents of which would have been familiar to the Scottish-born Sheila, who under her given name of Sheila Whytock, had danced with Pavlova and had been in the audience when Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe had performed at Covent Garden in 1911. Three years later she and her English husband John Faulkner , a silent film star ( and inventor of a fridge and an elastic sided shoe ) , nearly two decades her senior, emigrated to Australia where in 1927, aged 56, he fathered Ronald, whom he nicknamed ‘ Trader ‘ after seeing him exchange some of his illicitly distilled whisky for marbles. Continue reading

archive recently, journalist D. B. Wyndham Lewis declared:-

archive recently, journalist D. B. Wyndham Lewis declared:-