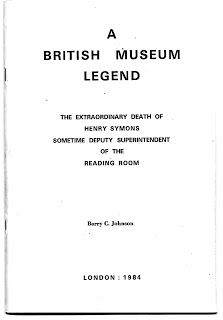

The removal of the British Library from Bloomsbury to St Pancras seems to have ushered in a new, more relaxed, attitude towards the rules governing who can acquire a reader’s card, according to a Guardian article of 2005. In it the Reading Room is described as being crowded with undergraduates, anxious, no doubt, to obtain an advantage over their peers. Under the rules prevailing in 1938, and which are contained in a Guide to the Use of the Reading Room, a copy of which we found recently in a box of ephemera, restrictions which perhaps Karl Marx might have recognised, were doubtless drawn up to limit the number of readers using the famous Rotunda. There is a distinctly schoolmasterly tone to the following advice:

The removal of the British Library from Bloomsbury to St Pancras seems to have ushered in a new, more relaxed, attitude towards the rules governing who can acquire a reader’s card, according to a Guardian article of 2005. In it the Reading Room is described as being crowded with undergraduates, anxious, no doubt, to obtain an advantage over their peers. Under the rules prevailing in 1938, and which are contained in a Guide to the Use of the Reading Room, a copy of which we found recently in a box of ephemera, restrictions which perhaps Karl Marx might have recognised, were doubtless drawn up to limit the number of readers using the famous Rotunda. There is a distinctly schoolmasterly tone to the following advice:

The Reading Room is in fact, as well as in theory, a literary workshop and not a place for recreation, self improvement or reference to books which are obtainable elsewhere…

No person will be admitted for the purpose of preparing for examination, of writing prize essays, or of competing for prizes, unless on special reason being shown; or for the purpose of consulting current directories, racing systems, lists of unclaimed moneys , or similar publications.

‘Racing systems’ and ‘lists of unclaimed moneys’. How redolent of the seedy world of Brighton Rock, which appeared a year later.

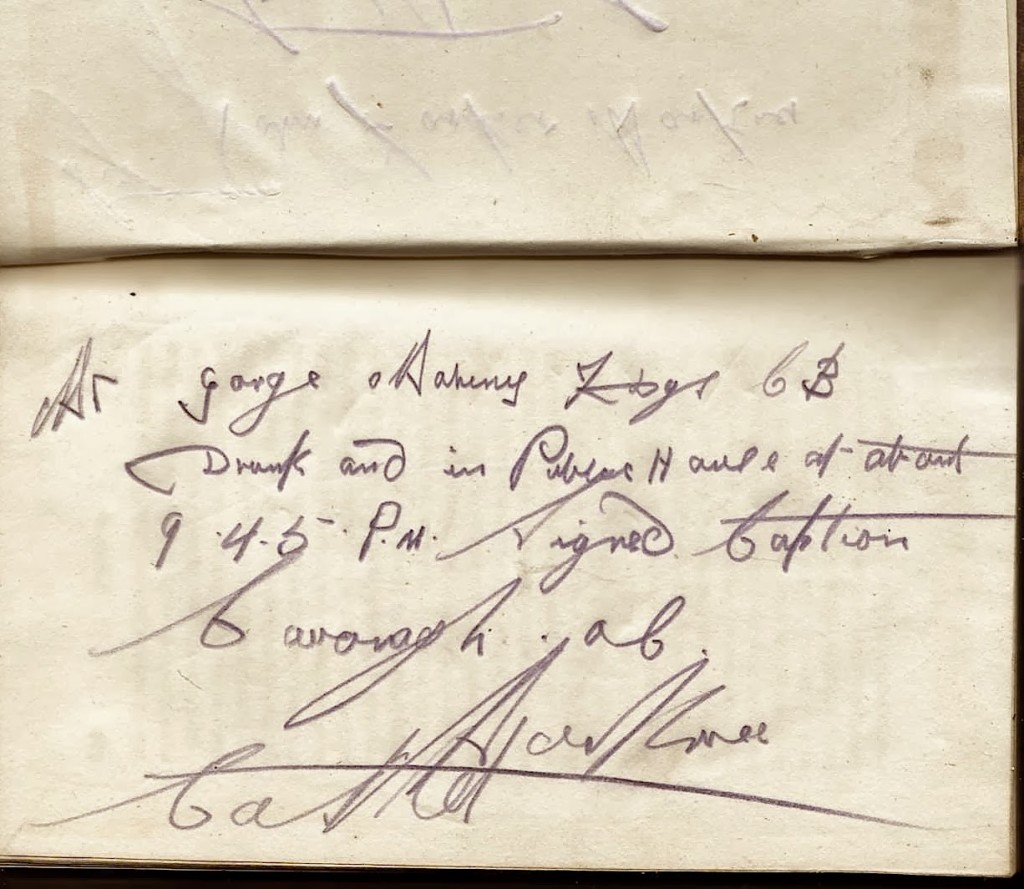

There is also a touch of ‘Greeneland’ about the advice offered to those prospective Readers seeking a testimony :

The Trustees cannot accept the recommendations of hotel-keepers or of boarding- house or lodging-house keepers in favour of their lodgers… [R.R.]