Found in an old herbal by the great botanist, apothecary and herbalist John Parkinson (1567 - 1650) a 'sovereign balsam' - a recipe for a curative oil made from rosemary, probably the most prolific of all herbs in Britain. The title of this splendid folio is: Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris : Or a garden of all sorts of pleasant flowers which our English ayre will permit to be noursed up: with a kitchen garden of all manner of herbes, rootes, and fruites, for meate or sause used with us, and an orchard of all sort of fruit-bearing trees and shrubbes fit for our land: together with the right ordering, planting, and preserving of them; and their uses and vertues. Collected by Iohn Parkinson Apothecary of London. Printed by Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young at the Signe of the Starre on Bread-Street Hill, London 1629. True to Ophelia's sad words in Hamlet ('There's rosemary. That's for remembrance. Pray you,love, remember...') the herb was long associated with preserving and invigorating the memory. The remedy calls for a fortnight's immersion in warm horse dung. As not many now have immediate access to hot horse manure, an airing cupboard might do for brewing the potion or the warm part of maturing compost. The 'strong glasse' could be replaced by a Kilner jar...

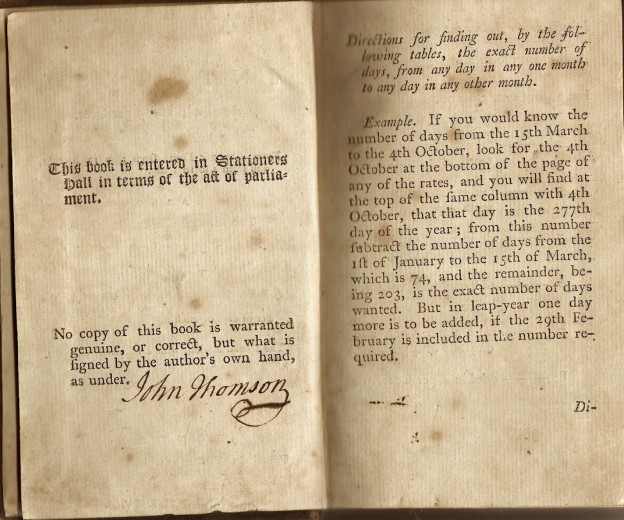

Rosemary is almost of as great use as Bayes, or any other herbe both for inward and outward remedies, and as well for civill as physicall purposes. Inwardly for the head and heart; outwardly for the sinewes and joynts: for civill uses, as all doe know, at weddings, funerals, &c. to bestow among friends : and the physicall are so many, that you might bee as well tyred in the reading, as I in the writing, if I should set down all that might be faid of it. I will therefore onely give you a taste of some, desiring you will be content therewith. There is an excellent oyle drawne from the flowers aloneby the heate of the Sunne, availeable for many diseases both inward and outward, and accounted a soueraigne Balsame:it is also good to helpe dimnesses of sight, and to take away spots, markes and scarres from the skin ; and is made in this manner. Take a quantitie of the flowers of Rosemary, according to your owne will eyther more or lesse, put them into a strong glasse close stopped, let them in hot horse dung to digest for fourteene dayes, which then being taken forth of the dung, and unstoppcd, tye a fine linnen cloth over the mouth, and turne downe the mouth thereof into the mouth of another strong glasse, which being let in the hot Sun, an oyle will distill downe into the lower glasse ; which preserve as precious for the uses before recited, and many more, as experience by practice may enforme divers, viz. for the heart, rheumaticke braines, and to strengthen the memory, whereof many of good judgement have had experience.

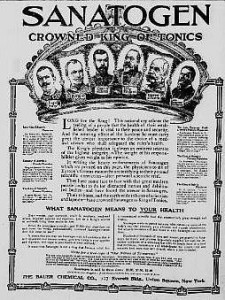

Remember the moral furore when Fay Weldom included references to Bulgari watches in her novel The Bulgari Connection ? She admitted being paid wheelbarrows of money for this blatant puff. But product placement in fiction is not new. Warreniana , the bestseller published in 1824 by the novelist, parodist and short story writer William Frederick Deacon (1799 – 1845), purports to be a collection of prose and verse by contemporary writers in praise of Warren’s Blacking– the boot polish bottled by the young Charles Dickens in the early 1820s. It is not known whether Deacon received a bung, but as the first edition appears to have been quite large, it is possible that the publishers were financially rewarded by Warren for printing an unusually large number of copies.

Remember the moral furore when Fay Weldom included references to Bulgari watches in her novel The Bulgari Connection ? She admitted being paid wheelbarrows of money for this blatant puff. But product placement in fiction is not new. Warreniana , the bestseller published in 1824 by the novelist, parodist and short story writer William Frederick Deacon (1799 – 1845), purports to be a collection of prose and verse by contemporary writers in praise of Warren’s Blacking– the boot polish bottled by the young Charles Dickens in the early 1820s. It is not known whether Deacon received a bung, but as the first edition appears to have been quite large, it is possible that the publishers were financially rewarded by Warren for printing an unusually large number of copies.