There was a comedy on BBC radio recently about a man who was transported back from today to early Victorian times. As I recall, he missed modern dentistry, and he also missed having something to listen to on his many walks. In James Runciman’s book of essays Joints in the Social Armour (Hodder 1890) he has this solution for the bored walker:

There was a comedy on BBC radio recently about a man who was transported back from today to early Victorian times. As I recall, he missed modern dentistry, and he also missed having something to listen to on his many walks. In James Runciman’s book of essays Joints in the Social Armour (Hodder 1890) he has this solution for the bored walker:

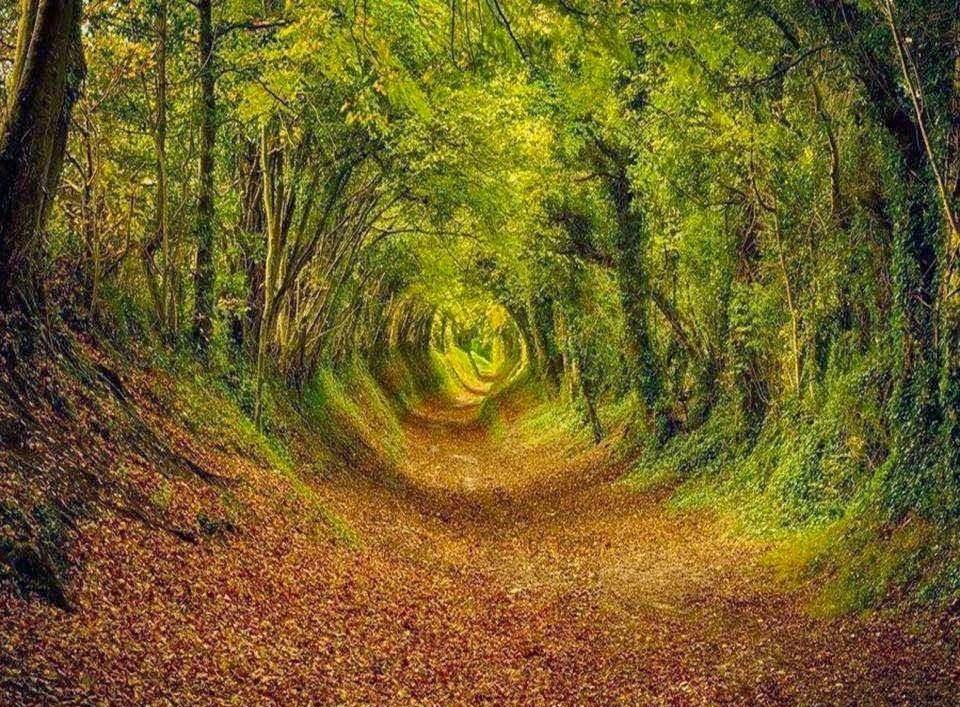

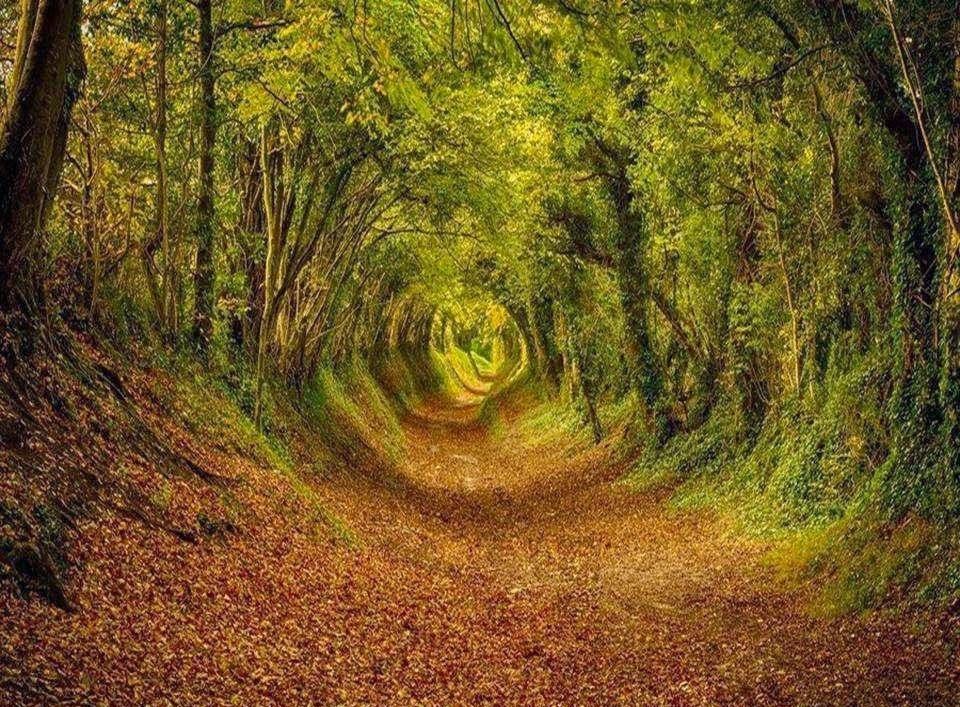

…then you find the advantage of knowing a great deal of poetry. I would not give a rush for a man who merely pores over his poets to make notes or comments on them; you ought to have them as beloved companions to be near you night and day, to take up the parable when your own independent thought is hazy with delight or even with sorrow. As you tramp along the whistling stretches amid the blaze of the ragworts and the tender passing glances of the wild veronica, you can take in all their loveliness with the eye, while the brain goes on adding to your pleasure by recalling the music of the poets. Perhaps you fall into step with quiver and the beat of our British Homer’s rushing rhymes, and Marmion thunders over the brown hills of the Border, or Clara* lingers where mingles war’s rattle with groans of the dying. Perhaps the wilful brain persists in crooning over the Belle Dame sans Merci; your mood flutters and changes with every minute you derive equal satisfaction from the organ- roll of Milton or the silver flageolet tones of Thomas Moore. If culture consists in learning the grammar and etymologies is of a poet’s song, then no cultured man will ever get any pleasure from poetry while he is on a walking tour; but, if you absorb your poets into your being you have spells of rare and unexpected delight.

*Possibly a reference to a poem by Robert Browning Red Cotton Nightcap Country or Turf and Towers (1873) about the love of a desperate man for a woman called Clara..

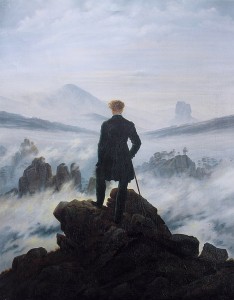

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes:

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes: