‘Publish or perish ‘ has long been an accept truism among academics; those University staff hoping for promotion will only achieve it if they are judged to have published a sufficient amount of published research to justify it. After all, university teachers are expected to researchas well as teach.

There must be many examples of University teachers failing to progress along the road towards a professorship, but your Jotter can think of two glaring cases. At my own University a certain expert in textual criticism, who was taken on by the department of English on the strength of a degree and a B. Litt in English , from Oxford University and who proved to be a popular teacher among his students ( his classes on bibliography and his lectures on Bob Dylan as a poet were highly appreciated) , failed to climb the greasy pole of academic promotion mainly because he published little or anything throughout his forty or so years in the department. He began as a Lecturer and retired (I believe) as one.

Another better known example was Monica Jones, the lover of Philip Larkin, who while a Lecturer in English at the University Of Leicester, failed to publish a single research paper or book, although she was regarded as a well-respected teacher with a particular interest in Sir Walter Scott. While her colleagues were promoted she remained firmly ensconced in the position as Lecturer, and retired holding that post. In her case, it wasn’t a lack of energy or intellectual capabilities that held her back. Like Larkin she left Oxford with a first class degree in English, but like Larkin, who in .’Vers de Societe’ resented having to ask an ‘ ass about his fool research ‘, didn’t see any point in publishing learned papers or books within her field. She preferred teaching, and according to those who attended her lectures and classes, was a gifted communicator. Continue reading

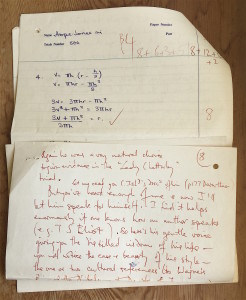

Found among the papers of the mathematician

Found among the papers of the mathematician