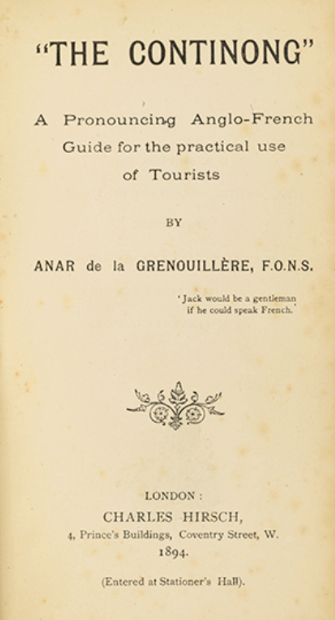

Poule mouillee Milksop

Profonde Pocket.

Quart d’oeil. Peeler; copper.

Qui-qui. The throat. Derivation unknown.

Faire du rabiau. To be punished.

Racaille. Rabble; a bad lot.

Raccourcir. To behead.

Raseur. Today this still means a bore or a drag.

Reluquer. To make eyes at.

Pincer un rigadon. To dance in a humorous way. Still used of a baroque dance

Rigolarde. Lark; fun.

Rigolo. Jolly; larky.

Rousse. The police. Today it means a redhead.

Sabote. Bungled ( presumably derived from sabotage).

Avoir le sac. To have plenty of money.

Sainte.Toute la sainte journee. The whole blessed day

Boire sec. To swill; to get drunk.

Sapin. A cab. It has always meant a fir tree.

Jouer comme une savate. To play badly.

Serin. Duffer. Faire le serin. To play the fool.

Payer en monnaie de singe. To let ( ) whistle for his money.

Continue reading

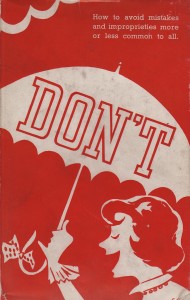

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

Discovered in an 1928 issue of John O’ London’s is an anecdote illustrating the importance of punctuation in a legal document.

Discovered in an 1928 issue of John O’ London’s is an anecdote illustrating the importance of punctuation in a legal document.