‘ A prolific and witty writer who contributed to the leading periodicals of the day, and was the author of over a score of books, many of which he illustrated himself, his best-known work, “ The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green “, was one of the great public successes of the last century ‘

So says George Hutchinson, writing of Edward Bradley in 1939, fifty years after his death. Bradley’s most well-known novel is rather forgotten today, but until quite recently your Jotter used to see copies of it regularly in second-hand bookshops, along with some of Bradley’s other less popular works. Along with other Victorian best-sellers, The Adventures of Mr Verdant Greenis unlikely ever to enter the curriculum of Englit departments anywhere, but as an example of the mid-century Victorian humour purveyed by magazines like Punch,to which Bradley contributed, it deserves to be read.

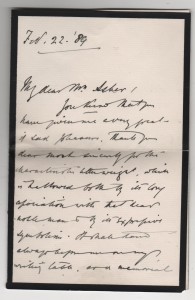

Bradley, a surgeon’s son, was born in Kidderminster in 1827. As a boy he was an avid sketcher and his artistic and growing literary interests were put to use as a contributor to a manuscript magazine, The Athenaeum, put out by a local literary society. While an undergraduate at Durham University in 1846 he began writing for Bentley’s Miscellany; the following year he contributed to Punch. In 1849 – 50 he was at Oxford, but did not matriculate. Presumably it was here that he found the material that he later used in The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green, an Oxford Freshman, to give his best-seller its full name. In 1850 Bradley accepted the curacy of Glatton-with-Holme in Huntingdonshire ( now part of Cambridgeshire), where he served for four years and where he wrote the first two parts of “ Verdant Green “ under the pseudonym Cuthbert Bede. At first the book was rejected by several publishers, despite Bradley’s growing reputation as a writer for the magazines, but eventually all three parts found a publisher in Nathaniel Cooke, who issued them as ‘ Books for the Rail ‘ . The parts were then consolidated into a book and this proved so popular that by 1870 it had sold 100,000 copies—equalling some of the best sales figures for novelists of the time. When its price was later reduced to sixpence the sale was more than doubled. Hutchinson claims that Bradley only made £350 from his best-seller, which is surprising considering that novelists like Dickens were astute enough to realise that the sales figures of their novels when first issued in series were likely to be even bigger for the one-volume books that emerged. However, it is unlikely that a clergyman like Bradley would have been sufficiently clued up on the powers that best-selling writers held over their publishers compared to a go-getting journalist like Dickens, who knew his worth as a popular writer and was prepared to negotiate lucrative terms with his own publishers. Continue reading

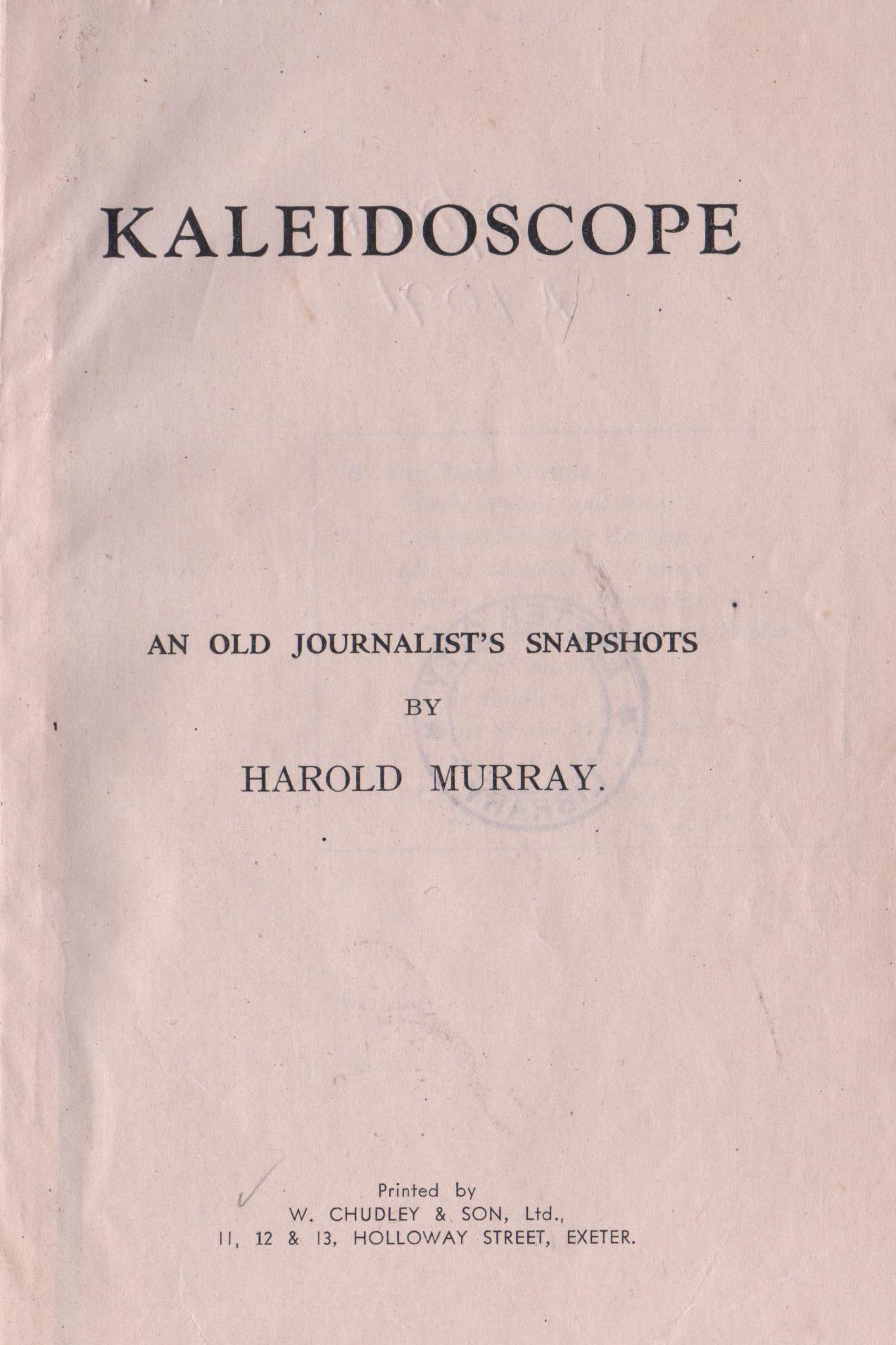

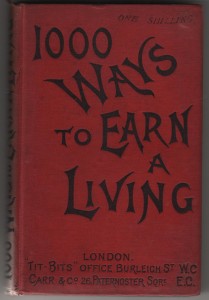

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

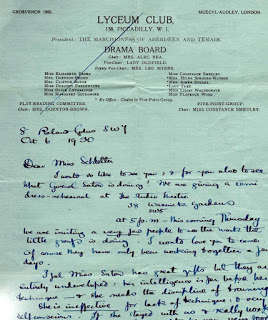

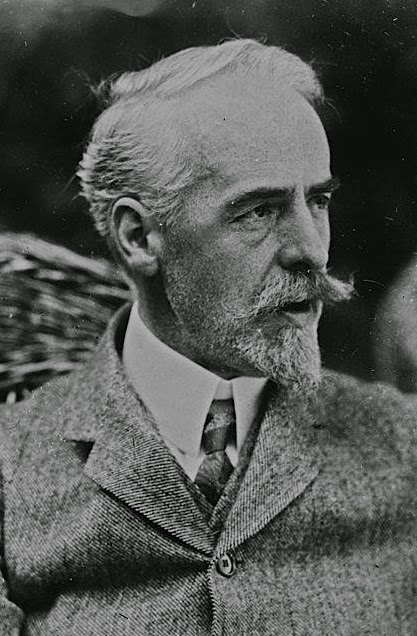

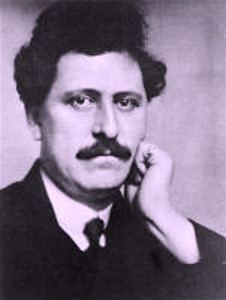

Found in a copy of the literary periodical Today for August 1919 is this advice for aspiring authors from its editor, Holbrook Jackson (pictured):

Found in a copy of the literary periodical Today for August 1919 is this advice for aspiring authors from its editor, Holbrook Jackson (pictured):