Entertainment:

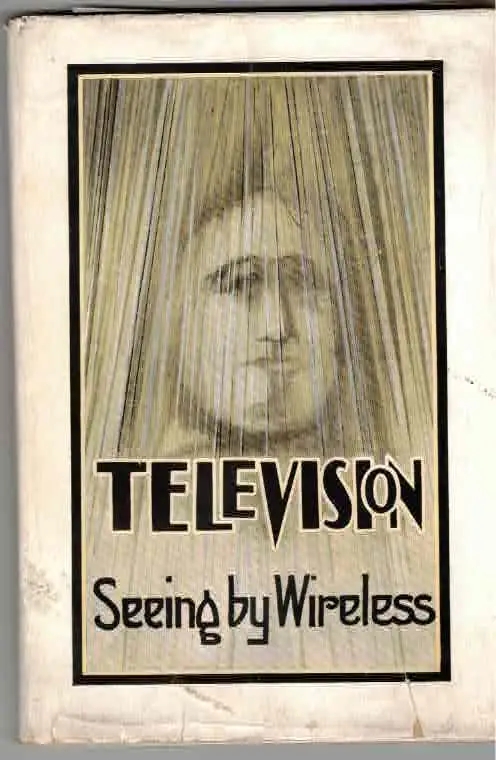

Music, vaudeville, movies, dance, theatre, television, radio, circus, the carnival, etc. If it amused, it was documented in books.

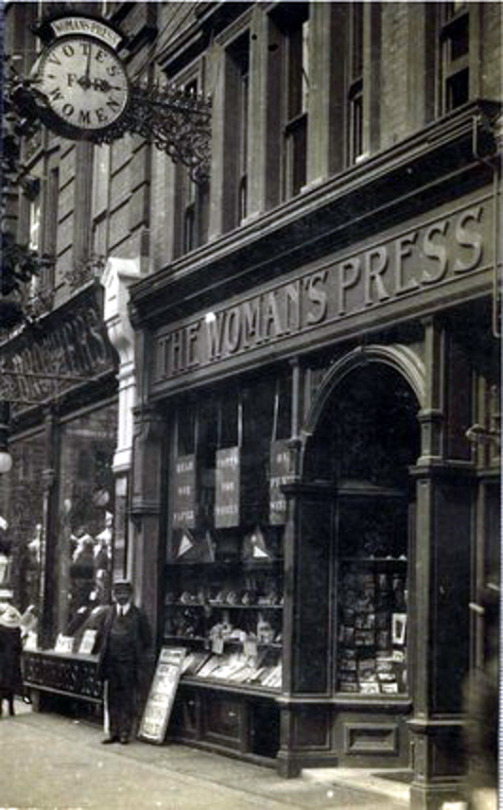

We have already looked at television and radio under ‘communication ‘. Under the heading ‘ music ‘ we can find bound volumes of sheet music going back to the mid eighteenth century, biographies of composers, songwriters and performers, and collections of folk music and old ballads. Some in the latter category are rare and sought after. Under the American term ‘ vaudeville ‘ are grouped the British Music Hall, Variety and Reviews and those interested in this type of entertainment may look for biographies of leading figures, such as Dan Leno or Marie Lloyd. However the most revealing ‘ literature ‘ relating to vaudeville are still theatre and concert programmes and copies of magazines devoted to this field, such as The Stage. One even more revealing source of information, particularly on Music Hall and Reviews are the manuscript Wages Books. Your Jotter found the Wage Book of the Wood Green Empire from 1912 – 24 in an auction a few years ago. From it he learnt that the leading performers of the day, such as George Robey and Marie Lloyd, were earning huge sums —£200 a week in some cases –compared to some lesser ‘turns’ who were lucky to receive £15 or £20. These star attractions were the movie stars of the day. The Wage Book also revealed the sad story of the faux Chinese illusionist, Chung Ling Soo, aka an American called William Ellsworth Robinson, who was shot on stage at the Empire in March 1918 after a bullet catching trick went horribly wrong. A real bullet had been loaded by mistake into the ‘gun’ aimed at him by his assistants. Robinson later died of his wounds. The Wages Book doesn’t pay tribute to the dead man, but it does record a large sum of money given in compensation to his widow. Boris Karloff later portrayed Robinson in a popular film.

Books on movies and movie stars, of which there are many, are collected by film buffs around the world. Years ago your Jotter interviewed one of the biggest dealers in the performing arts, the American Elliott Katt who revealed, that most of his customers were professionals from the movie industry, notably in Hollywood, and that one particular star, Michael Jackson, always insisted that he close his shop when he visited, such was the clamour from fans. Katt also had a fund of anecdotes relating to the very rare and valuable books on early cinema that he always kept in stock.

The history of dance is a popular field for collectors, though books on this subject are few. The most valuable items usually date from the eighteenth century and are often written by dancing masters.

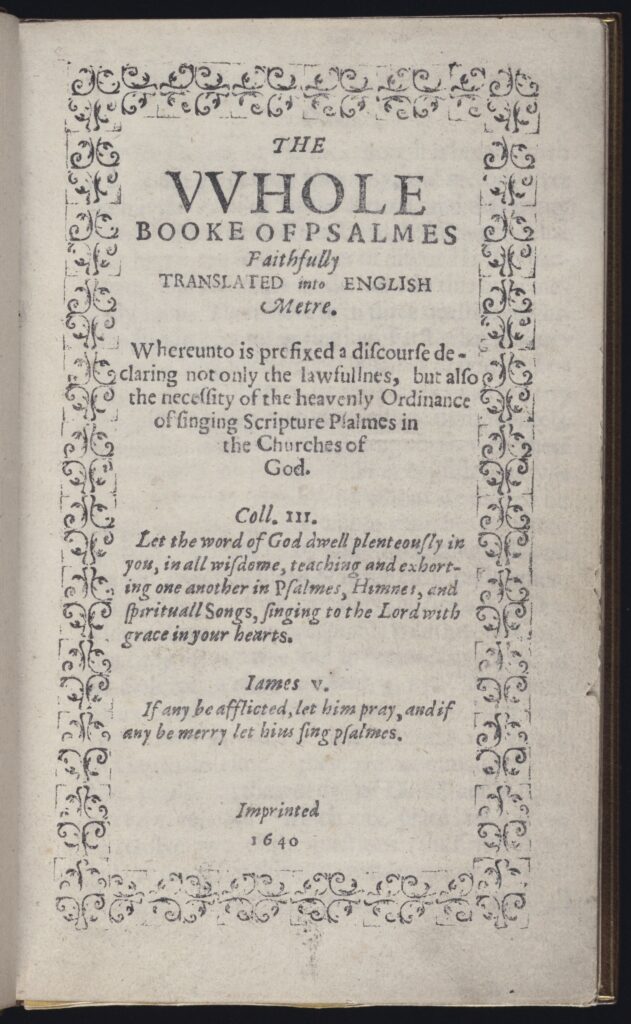

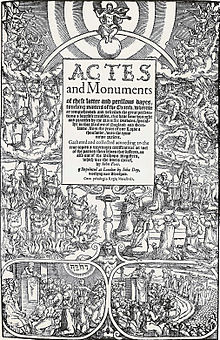

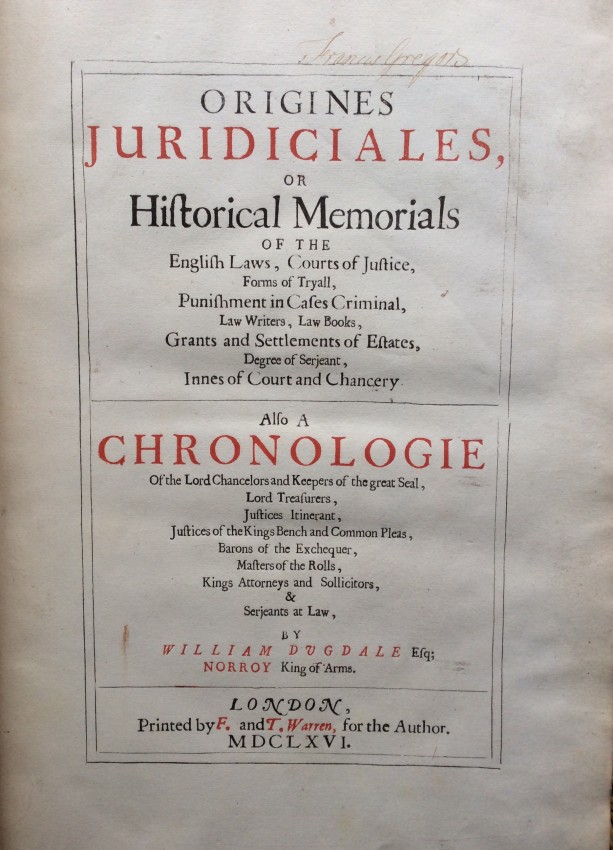

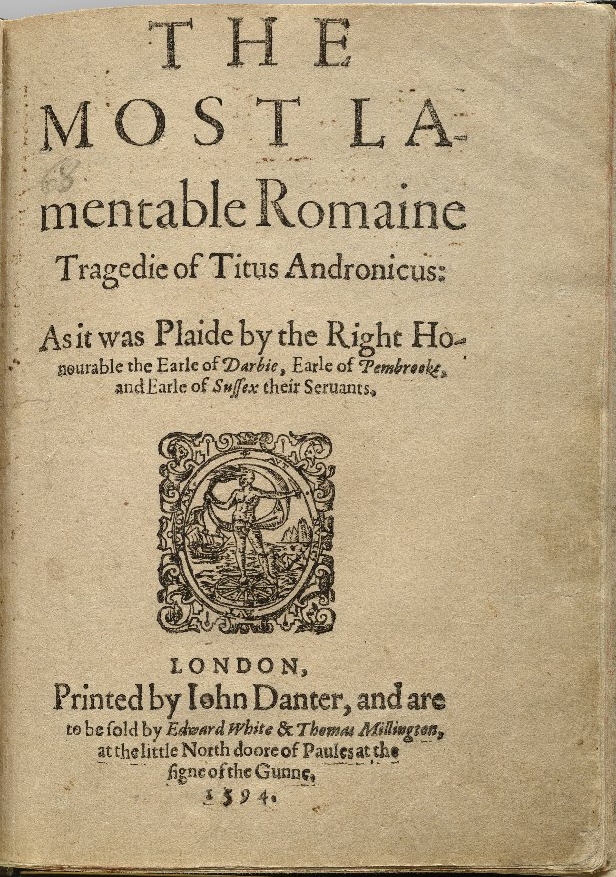

Books relating to the theatre can be plays dating back to the time of Shakespeare and here the most elusive ( and expensive) are the so-called ‘quartos’ of single plays by the Bard printed (often badly) in small numbers for the use of actors and perhaps theatregoers at the time. Back then Shakespeare’s plays were well regarded and popular, but their author had yet to attain the status of genius and national figure that the appearance of the First Folio in 1623 helped to foster. Thus the original quartos weren’t valued and most were thrown away when they fell to pieces through over-use. If a quarto of one of his greatest plays were to come onto the market now it would cause an extraordinary furore and command a price close to a million pounds for its rarity value alone, particularly if it contained annotations by one of the Bard’s company. Copies of the First Folio and subsequent Folios also fetch large sums, but are much more common. More common still are the various, often bowdlerised editions of Shakespeare that appeared from the press throughout the eighteenth century. These are always quite cheap, reflecting as they do the tastes and morals of their editors rather than the inimitable greatness of the Bard. For this reason they are probably best avoided as texts, though they have a novelty value.

Continue reading