Found—a clipping from the mid Victorian Jerrold’s Weekly News regarding the legendary Sir Richard Phillips—a sort of Robert Maxwell of his time—and the witty physician, Dr John Wolcot (aka Peter Pindar).

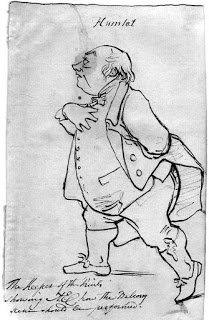

‘Having mentioned Sir Richard Phillips, I must observe that his shop in Bridge-street was the lounge of a good many literary men. Philips was a shrewd man, fresh-coloured and stout. He lived to the age of eighty. He ate no flesh food, on the ground of his affection for animals. He had a notion in the latter part of his life, that he had discovered a system that would supersede Newton’s theory of gravity. Wolcot said that Phillips, notwithstanding his refusal of animal diet, had no objection to feed upon the brains of authors, and that he loved wine, but kept no beef-steaks. He referred here to Pitt, who it is said ‘would drink wines, but who kept no concubines’, in allusion to the notorious indifference of the Minister towards the fair sex. Walcot said that fact alone proved the Minister a great rascal. One of Pitt’s advocates, observing that it was no matter, Pitt was married to his country: ‘Yes’, said Wolcot, ‘and a cursed bad match it was for his country ‘. Now Doctor, that is too bad, was the reply: ‘You yourself have been but a bad subject of the King’. ‘It may or may not be so,’ said Wolcot, ‘but I can tell you the King has been an excellent subject for me ‘. Phillips used to call upon the doctor after the latter became totally blind, in order to get verses from him for the old Monthly Magazine. When he got them, so niggardly was Phillips, that the doctor could never obtain a second copy of the magazine to send to a friend. ‘I am constantly giving him something ‘, said the doctor. ‘When I ask for a couple of copies of my lines, he said I shall have them “at the trade price”. I will give him no more; ‘he is a Shylock.’ Continue reading