Taken from the Appendix to his Shadows of the Old Booksellers (1927 reprint of book originally published in 1865)

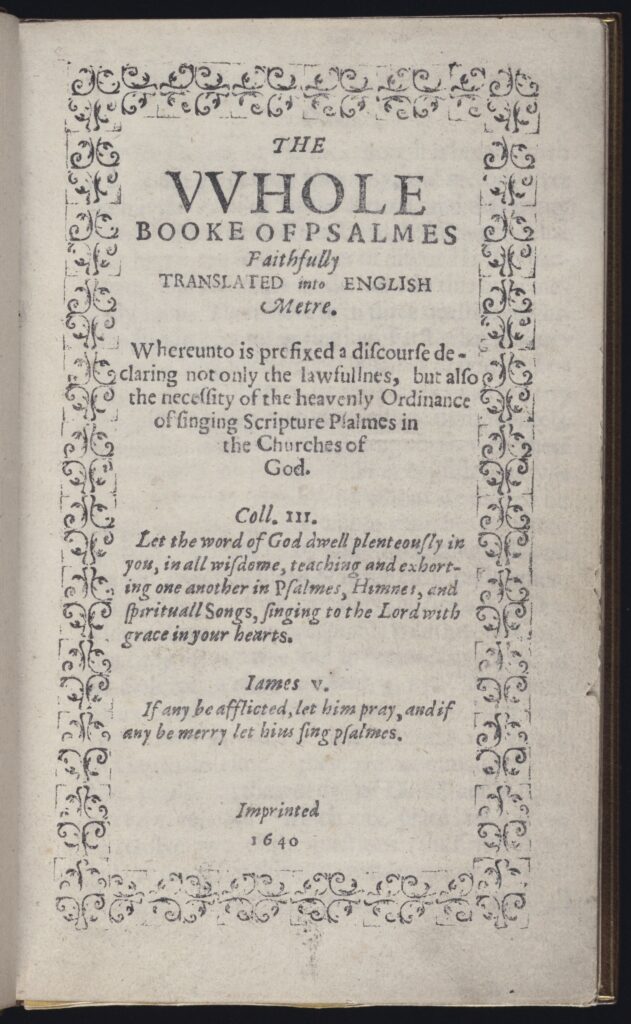

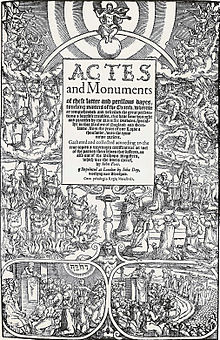

The first period of the English Press, 1471 – 1603

In 1540 ( Grafton) printed only 500 copies of his complete edition of the Scriptures,

‘ and yet so great was the rush to this new supply of the most important knowledge, that we have existing 326 editions of the English Bible, or parts of the Bible, printed between 1526 and 1600 ‘ .

‘The early English printers did not attempt what the continental ones were doing for the ancient classics. Down to 1540 no Greek book had appeared from an English press. ‘ Oxford had printed only a part of Cicero’s Epistles; Cambridge, no ancient writer whatever:-only three or four old Roman writers had been reprinted, at that period, throughout England.

Ames and Herbert have recorded the names of 350 printers operating during 1471 – 1600 in England and Scotland, including foreign printers producing books for England. During this same period 10,000 titles appeared, though some were only single sheets…’

‘The Privy Purse Accounts of Elizabeth of York’, published by Sir H. Nicolas records that in 1505 twenty pence were paid for a Primer and a Psalter. In 1505 twenty pence would have bought half a load of barley, and were equal to six days’ work of a labourer. In 1516, Fitzherbert’s Abridgement, a large folio law book, then first published, was sold for forty shillings. At that time forty shillings would have bought three fat oxen…’

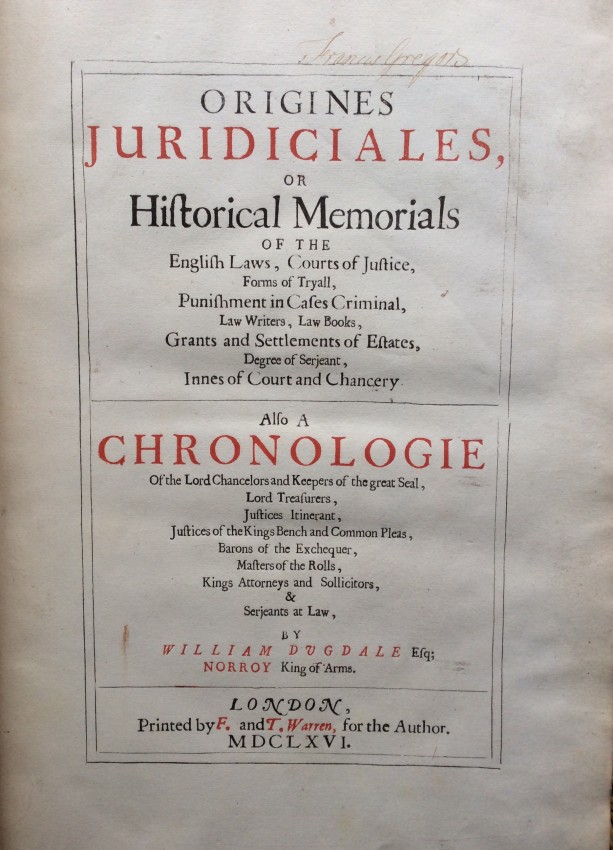

The second period of the English Press, 1603 – 1688

‘…perhaps all circumstances considered, the least favourable to the diffusion of knowledge of any period in our whole literary history… Controversy… began to be rife in England; and the spirit at least exploded in such a torrent of civil and ecclesiastical violence in the reign of James’ successor, as left the many little leisure for the cultivation of their understandings. The press was absorbed by the productions of this furious spirit. There is in the British Museum, a collection of 2,000 volumes of Tracts issued between the years 1640 and 1660…

‘This most curious collection was made by a bookseller of the name of Tomlinson, in the times when the tracts were printed; it was bargained for, but not bought, by Charles II; and was eventually bought by George III, and presented by him to the British Museum.’

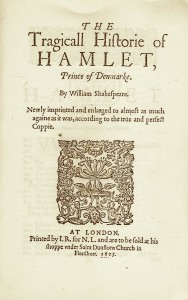

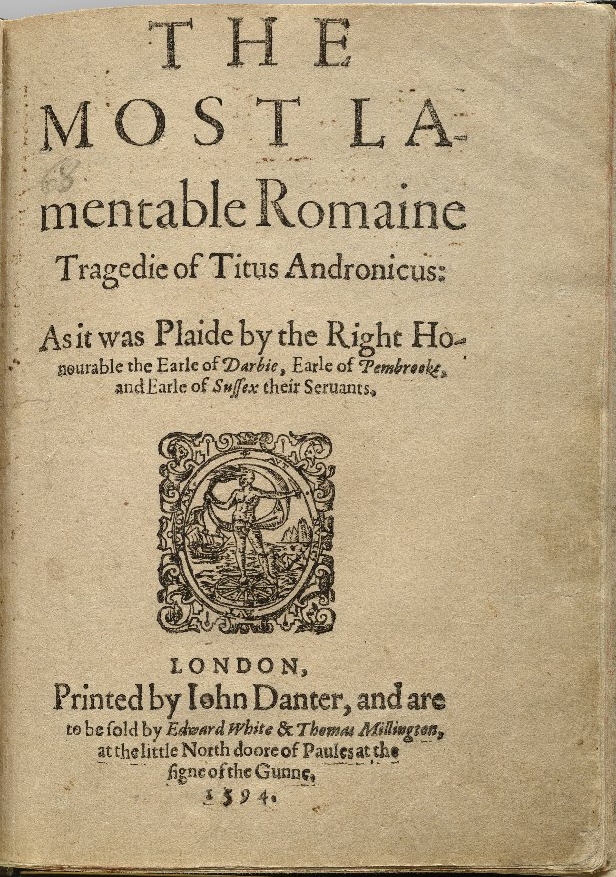

‘The number of impressions of new books unconnected with controversial subjects, printed during these stormy days, must have been very small. Dr Johnson has remarked that the nation, from 1623 to 1644 was satisfied with two editions of Shakespeare’s Plays, which, probably together did not amount to a thousand copies.’

‘ At the Restoration our national literature, with a very few grand exceptions, put on the lowest garb in which literature can be arrayed…Under such a state of things, Milton received fifteen pounds for the copy of Paradise Lost; and an Act of Parliament was passed that only twenty printers should practise their art in the kingdom. We see by a petition to Parliament in 1666, that there were only 140 “ working printers “ in London…’

‘…At the fire of London, in 1666, the booksellers dwelling about St Paul’s lost an immense stock of books in quires, amounting, according to Evelyn, to £200,000, which they were accustomed to store in the vaults of the metropolitan cathedral, and of other neighbouring churches…there was considerable activity once more in printing. The laws regulating the number of printers son after fell into disuse, and they had long fallen into contempt. We have before a catalogue ( the first compiled in this country) of “ all the books printed in England since the dreadful fire, 1666 to the end of Trinity Term 1680 “, which catalogue is continued to 1685, year by year. A great many—we may fairly say one half—of these books, are single sermons and tracts. The whole number of books printed during the fourteen years from1666 to 1680, we ascertain, by counting, was 3,550, of which 947 were divinity, 420 law, and 153 physic,—so that two-fifths of the whole were professional books; 397 were school books , and 2653 on subjects of geography and navigation, including maps. Taking the average of these fourteen years, the total numbe4r of works produced yearly was 253; but deducting the reprints, pamphlets, single sermons, and maps, we may fairly assume , that the yearly average of new books was under 100. Of the number of copies constituting an edition we have no record; we apprehend it must have been small, for the price of a book, as far as can ascertain it, was considerable….In a catalogue, with prices, printed twenty-two years after one we have just noticed, we find that the ordinary cost of an octavo was five shillings.

Continue reading

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

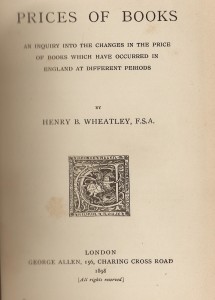

H.B.Wheatley’s Prices of Books (1898) is a real eye opener, not just for the prices realised by truly great and important books, but also for those works which today would not fetch ( in real terms) anything like the sums that our Victorian forebears might have paid.

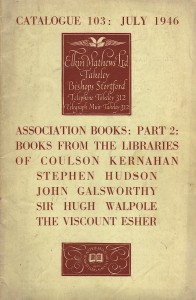

H.B.Wheatley’s Prices of Books (1898) is a real eye opener, not just for the prices realised by truly great and important books, but also for those works which today would not fetch ( in real terms) anything like the sums that our Victorian forebears might have paid. near Bishops Stortford, probably contained descriptions of books and manuscripts by one of the directors, Ian Fleming, an avid book collector. It’s tempting to imagine the future creator of James Bond trawling through some of the items in the catalogue in search of likely material.

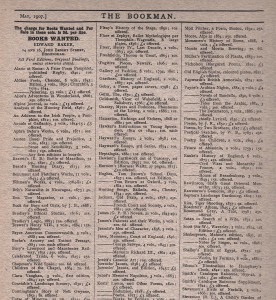

near Bishops Stortford, probably contained descriptions of books and manuscripts by one of the directors, Ian Fleming, an avid book collector. It’s tempting to imagine the future creator of James Bond trawling through some of the items in the catalogue in search of likely material. Before we report on the bargains available in May 1908 at Edward Baker’s Great Bookshop in John Bright Street, Birmingham (contrast it with Birmingham City Centre today, where there is not a single second hand bookshop ), let us examine what Mr Baker was prepared to give for top-end first editions in 1907 as advertised in The Bookman for May of that year.

Before we report on the bargains available in May 1908 at Edward Baker’s Great Bookshop in John Bright Street, Birmingham (contrast it with Birmingham City Centre today, where there is not a single second hand bookshop ), let us examine what Mr Baker was prepared to give for top-end first editions in 1907 as advertised in The Bookman for May of that year.