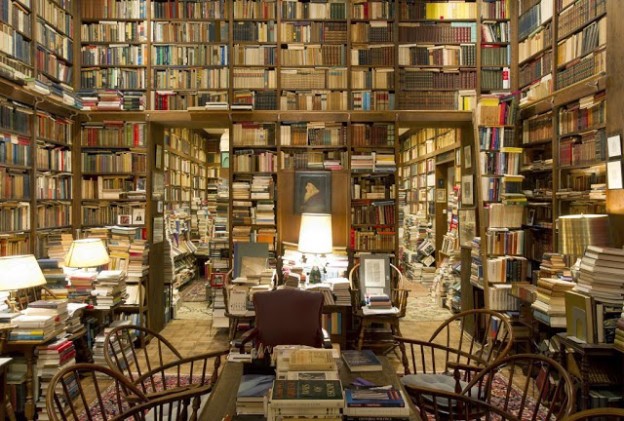

Solomon Pottesman ( 1904 – 78) was one of the best known ‘ characters’ in London’s post-war world of antiquarian book dealing. Socially awkward, often exasperating in the eyes of auction staff, such as O.F.Snelling, who paints a rather uncharitable picture of him in his

Rare Books and Rare People, he was more appreciated by fellow bibliophiles like Alan Thomas, who not only enjoyed his company, but like so many other dealers and collectors, thoroughly respected his encyclopaedic knowledge of incunabula. Indeed, so expert in his field, was Solomon, that he was almost universally known as ‘Inky’.

So, in 1960, when Pottesman announced that he had just published a book, everyone assumed that this would be a wonderfully scholarly work on pre-1500 printing and publishing. Imagine the disappointment when those few friends and colleagues who Pottesman honoured with a complimentary copy of the book in question received a slim unpaginated pamphlet in blue card covers, and printed at his own expense, entitled

Time and the Playground Phenomenon. This turns out to be an exploration of Space, Time and Memory elicited by the author’s shock, twenty years earlier , on returning to the school playground he had left aged 14 to discover that it ‘ HAD SHRUNK TO A FRACTION OF ITS FORMER SELF’ (his block capitals). Seemingly of a philosophical turn of mind (another trait of which his acquaintances were unaware), Pottesman became so obsessed with this phenomenon, that he resolved to explore it. He had already rejected as fallacious the more obvious explanation that he had grown and’ as a consequence, the playground seemed small’ by rightly arguing that the other haunts of his childhood that he had revisited had not also diminished in size.

Pottesman then embarks on a quasi phenomenological theory in which he brings to his argument such learned commentators as Lucretius, Darwin, Kant, Taine, William James and Pavlov. His central premise is that the MEMORY of that playground had grown with him as a static ‘cut-out’ which through the years becomes a sort of unmodified hallucination. With physical growth, this memorised image grows larger and thus when time plays a part and the actuality is later revisited it seems much smaller compared with the memorised image.

‘Time is revealed as subjective in that the object is growing smaller in, and relative to, space-with-time, or consciousness of the percipient, but, by this very process, phenomenal time is shown to depend on the identical object indifferent to perception, the subjective and objective are revealed as a synthesis, and time is shown to be inseparable from the duration of objects’ (author’s bold type).

It is easy to understand why the no nonsense Snelling, who was more interested in devising accurate catalogue entries, and who wrote at least one book about boxing, would have dismissed Inky’s philosophical explorations as the worst kind of solipsism. But it is unlikely that any of Pottesman’s other colleagues would have felt any different. Some might have been a little embarrassed. I would like to think that one or two who received a copy of his book, which I was sent gratis by a dealer not long ago, were rather impressed. [RMH]

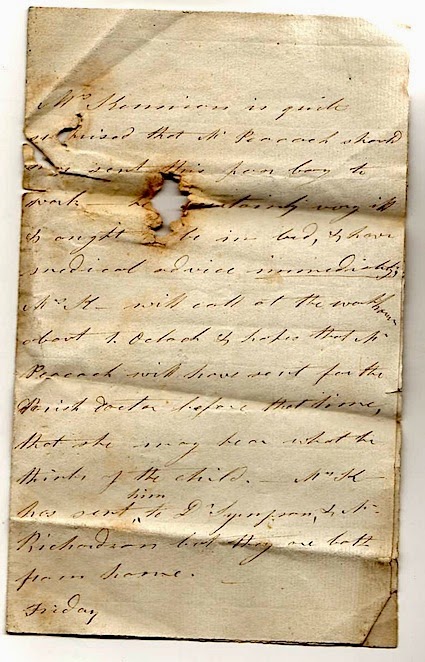

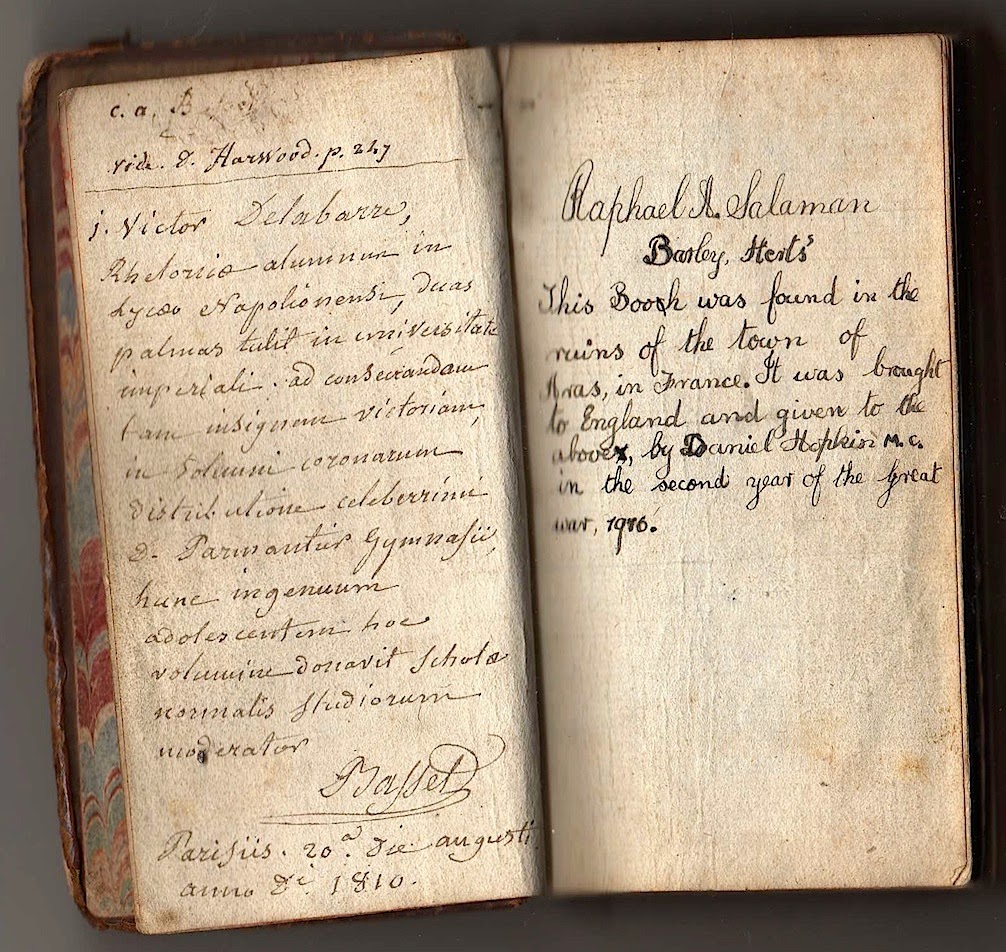

The illustration above is of one of his greatest finds - a stationer's list - for a quarto edition of Shakespeare's (possibly) lost play Love's Labour's Won'.