When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

Sir Ernest Gowers was a senior civil servant whose best-selling popular grammar Plain Words (1948), was devised to help his fellow civil servants write clear and correct English. In 1951, admitting that its format could be improved, Gowers brought out ABC of Plain Words.Nearly 70 years on this guide can still be used alongside other more recent grammars, such as Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots and Leaves. Most of the advice proferred by Gowers still applies, but some might raise a few eyebrows among the journalists of today. Here are a few words and their definitions that might provoke discussion today.

Deadline.This is a word known to all hacks, but Gowers chooses to define deadline conventionally as ‘ a line drawn round a military prison beyond which a prisoner may be shot down’. I don’t know which dictionary Mr Gowers was using, but the Chambers dictionary we use here at Jot HQ gives two definitions besides this one—1) ‘ the time that newspapers, books etc going to press’ 2) ‘a fixed time or date terminating something’. Gowers doesn’t even mention what ninety percent of people nowadays (and probably in 1951 too) would recognise as the most common definition of deadline.

Decimate.Gowers is right about the word decimate, however. He defines it as meaning to reduce by one tenth, not to one tenth. No writer today should get away with saying that troops were decimated, mainly because no-one would possibly know that soldiers in a battle could be reduced by exactly one tenth !

Dilemma.This is another word of precise meaning. It does not mean that someone has a number of difficult courses of action. He or she has exactly two. Continue reading

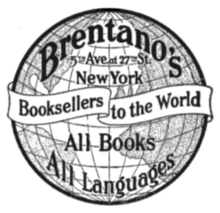

Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.

Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.

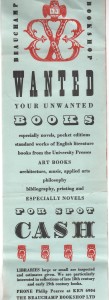

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.

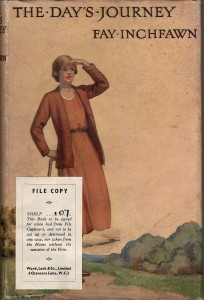

Discovered at Jot HQ is this first edition of one of the ‘Homely Woman’ pocket volumes by the prolific female writer Fay Inchfawn ( aka Elizabeth Rebecca Ward, 1880 – 1978), whose work is forgotten now, but whose books, which included popular verse, religious works and children’s literature, were once, to quote the blurb from her publisher Ward, Lock & Co in 1947, ‘to be found in countless homes, for more than half a million have been sold’.

Discovered at Jot HQ is this first edition of one of the ‘Homely Woman’ pocket volumes by the prolific female writer Fay Inchfawn ( aka Elizabeth Rebecca Ward, 1880 – 1978), whose work is forgotten now, but whose books, which included popular verse, religious works and children’s literature, were once, to quote the blurb from her publisher Ward, Lock & Co in 1947, ‘to be found in countless homes, for more than half a million have been sold’.

H.B.Wheatley’s Prices of Books (1898) is a real eye opener, not just for the prices realised by truly great and important books, but also for those works which today would not fetch ( in real terms) anything like the sums that our Victorian forebears might have paid.

H.B.Wheatley’s Prices of Books (1898) is a real eye opener, not just for the prices realised by truly great and important books, but also for those works which today would not fetch ( in real terms) anything like the sums that our Victorian forebears might have paid. Joe and Arthur Rank

Joe and Arthur Rank