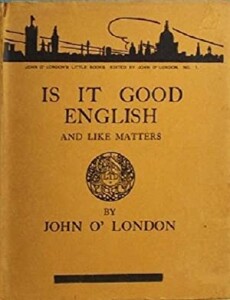

Taken from Is it Good English ? by John O’London (1924)

Words whose meanings have changed over the years

1) Evince

John O’ London complained in 1924 that the word ‘evince’ should be avoided. Since then your Jotter has seen it used several times, but usually not by journalists or by others whose job it is to write lucidly. Here is Mr O’ London’s case for rejecting it out of hand:

‘A word which careful editors are constantly striking out of accepted manuscripts is ‘ evince. ‘It is used unbecomingly in all such phrases as “ he evinced a great desire “ or “ his passion for study was evinced by his fine library.”. To evince means, in its primary but now obsolete sense, to subdue or conquer, and is so used by Milton: “ Error by his own arms is best evinced.” Its proper meaning, now, is to prove, to make manifest, to show in a clear manner. It is too strong a word for either of the above phrases. A man may” have”, “ show”, or “ reveal” a desire ; his passion for study may be “ indicated “ or “ betoken “ by his library. Good writers have little use for the verb “ evince.”

1) Phenomenal

A word that has all but turned somersault. It is now widely used —but never by good writers—in the sense of unusual or wonderful, and we even meet with the phrase ‘ almost phenomenal ‘. A phenomenon is not a wonderful event or spectacle, but simply an event, spectacle, or observed process, as in the sentence ( Huxley’s): ‘ Continue reading

If Everybody’s Best Friend ( 1939) is to be believed, people were still debating the propriety of men giving up seats to women, whether or not it was necessary to doff a hat to a lady or where a man should walk on a pavement when accompanying a lady, as they had done for centuries before and perhaps still do. On the question of who should pay on a night out, to an earlier generation brought up before the advent of Women’s Liberation, there is no question that a man should pay for everything. Notice that it is tacitly assumed that once the man and woman are married, it is certainly the husband who must pay for a meal and for seats in a theatre or cinema, even though the wife may have an income from her job. But have things changed that much ?

If Everybody’s Best Friend ( 1939) is to be believed, people were still debating the propriety of men giving up seats to women, whether or not it was necessary to doff a hat to a lady or where a man should walk on a pavement when accompanying a lady, as they had done for centuries before and perhaps still do. On the question of who should pay on a night out, to an earlier generation brought up before the advent of Women’s Liberation, there is no question that a man should pay for everything. Notice that it is tacitly assumed that once the man and woman are married, it is certainly the husband who must pay for a meal and for seats in a theatre or cinema, even though the wife may have an income from her job. But have things changed that much ?

and perhaps still newsworthy, according to Tatler’s Thousand Most Socially Significant People in 1992.

and perhaps still newsworthy, according to Tatler’s Thousand Most Socially Significant People in 1992.

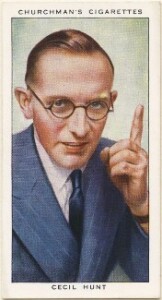

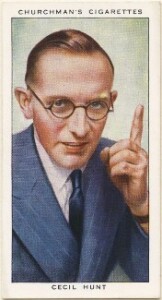

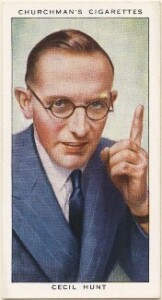

Cecil Hunt ( 1902 – 54) was a journalist, editor, novelist and anthologist best known throughout the English-speaking world for his compendiums of schoolboy ‘ howlers’. His first collection appeared in 1928 and proved to be a best-seller. At various times afterwards he produced other anthologies of howlers as well as guides to journalism, which he had studied at King’s College, London, and creative writing, books on the origins of words and a collection of unintentionally funny letters. He also wrote novels under two pseudonyms ( Robert Payne and John Devon). Interestingly, Hunt was President of the London Writers’ Circle and was instrumental in establishing Swanwick Writers’ Summer School. He died at just 51, but ironically his wife lived to be 107.

Cecil Hunt ( 1902 – 54) was a journalist, editor, novelist and anthologist best known throughout the English-speaking world for his compendiums of schoolboy ‘ howlers’. His first collection appeared in 1928 and proved to be a best-seller. At various times afterwards he produced other anthologies of howlers as well as guides to journalism, which he had studied at King’s College, London, and creative writing, books on the origins of words and a collection of unintentionally funny letters. He also wrote novels under two pseudonyms ( Robert Payne and John Devon). Interestingly, Hunt was President of the London Writers’ Circle and was instrumental in establishing Swanwick Writers’ Summer School. He died at just 51, but ironically his wife lived to be 107.

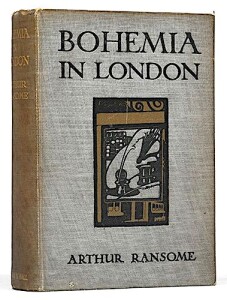

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.