A lost classic of ‘thirties dormitory suburbia ?

When a comparatively recent book becomes hard to find one is tempted to wonder exactly why. If it isn’t a private press production in a limited edition, or wasn’t the victim of a fire that devoured most copies in a publisher’s warehouse, or wasn’t withdrawn from publication due to a law suit, or bought up by the author who didn’t want readers to buy it, then one is entitled to ask why it is so scarce . There is only one copy ( at some point there were two, but one was sold) of The Bus Stops at Binham Lane by Stacey W(illiam) Hyde, published by Jonathan Cape in 1936, on abebooks. This particular copy is in only fair condition and lacks its dust jacket, but the vendor wants a cool £29 for it. Does he know something about the book that we don’t ?

Perhaps he read a review of it by L. A. Pavey in the Winter 1936 issue of Now and Then in which the reviewer praises the author for a remarkably shrewd eye for the idiosyncrasies of a couple newly displaced from one established piece of suburbia into a brand new estate development built on fields and country lanes on the edge of a town. Hyde’s general theme is the effect on those who began their post-war life in the heart of the country but who ended up ‘ in a Calvary of estate development and jerry-building’ to a place with (to quote Hyde himself)

‘homes strung out interminably along the white skewers of their concrete roads; there were no churches among them, no schools, no parks, shops only in isolated pairs, no pubs, no halls, no libraries, no cinemas—nothing to indicate that a people…had come to live among the immemorial quietudes of Binham fields’.

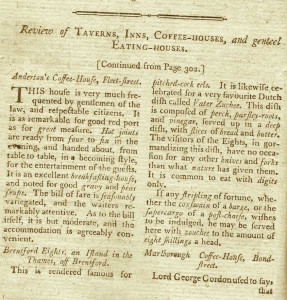

If we put aside the town-planning issues temporarily and focus on the sociological ones, it’s possible to imagine why The Bus Stops at Binham Lane is regarded as an important record of how the displaced inhabitants of new housing estates were obliged to make the best of their ‘ bleak sort of wilderness ‘. If we return to the town-planning issues and perhaps view them with a sociological eye , the book could be read alongside such classics as William Clough-Ellis’s Britain and the Beast , C.E.M. Joad’s The Untutored Townsman’s Invasion of the Country (1946), or for that matter, the Shell Guides of the ‘thirties and their temporary replacements of the forties , the Murray’s Architectural Guides, which cast a baleful eye on the ribbon development and the new arterial roads that disfigured so many of the outer suburbs of London. Needless to say, many of these issues were also addressed by John Betjeman in his early poems as well as in his excellent First and Last Loves. At a slightly later date, the late great Ian Nairn highlighted them in his pioneering Outrage and Counter Attack.

In his book-length diatribe Joad discusses the rise of what he calls ‘ dormitory England’ and here he uses the same objections in 1949 as Hyde had used in 1936.

This ‘England of the factory and the spreading dormitory suburb’, Joad complains,

…is a lonely England and lacks almost all those places of meeting in which human beings have traditionally gathered, known their neighbours and felt the stirrings of civic consciousness. There are no assembly halls, no theatres, few churches, no civic centres; in many garden cities there are no pubs or very few. There are only those awful isolating cinemas where the inmates sit hand in hand, absorbing emotion like sponges in the dark…These spreading suburbs have no heart and no head…’

Continue reading