Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who died a few months ago aged 101 was a hero to many in the fifties — as publisher, spokesman, and owner of San Francisco’s City Lights Bookshop, he became the eminence griseof the Beat generation. He was also a best-selling poet with his second collection, A Coney Island of the Mind(1958). It is less well known that in the UK this collection was received far less enthusiastically, to say the least. In fact it was pummelled by fellow poet and critic Al Alvarez, who reviewed regularly for the Observer, where this review appeared in 1958.

Alvarez, like Geoffrey Grigson, who despised him for promoting the ‘ confessional school ‘ and for approving suicide, among other things, had a reputation for physical and mental toughness. A rock-climber and poker-player, who published books on both subjects, he despised Romanticism in poetry, and the genteel perspective of poets like Larkin and Betjeman, preferring the gritty world view of writers such as Lowell and Berryman. And like any tough guy Alvarez spoke his mind. If a poem didn’t measure up he said so without equivocation. And in his view, Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mindwas bad. In fact it was ‘extraordinary bad’. Alvarez’s review is worth reading, not only for what he says about Ferlinghetti:

Mr Ferlinghetti’s reputation largely depends on his extra-literary activities; he has stage- managed many of the San Francisco Beatniks; he owns the City Lights Bookshop where they sometimes meet; from it he has published some of their verse. He has also fooled around with that latest sub- literary form of publicity, poetry and jazz…’

But also how he saw the Beatnik movement.

‘ The Beatnik’s pose is one of rejection and eccentricity; they say ‘ no’ to society, daddy and sense, and ‘yea ‘ (Whitman’s word) to the great exploited body of Mother America and to what Jung, had he seen them, might have called ‘ the collective inertness. ‘ None of this, of course, makes up a literary revolution. It is simply a minor revolt, another scrabbling for fame and rewards with different slogans. And Mr Ferlinghetti is, at least, less belligerent than his colleagues. At heart he is nice, sentimental, rather old-fashioned writer who, he admits, ‘ fell in love with unreality’ early and has since developed a penchant for words like ‘ stilly’, ‘shy’, ‘sad’, ‘ mad’, and ‘ ah’. He also has a pleasant little talent for verbal whimsy—‘ eager eagles’, ‘ the cat with future feet ‘, ‘foolybears’ and the like—which no invoking of the usual private parts will change from low-level Edward Lear into tough surrealism.

Continue reading

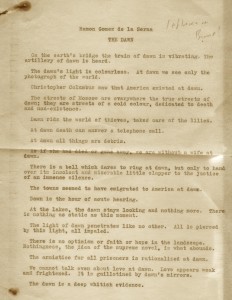

poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

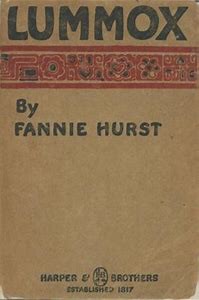

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

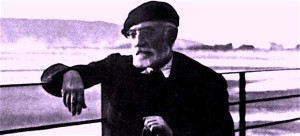

Found in Essays and soliloquies by Miguel de Unamuno (London: Harrap 1924) this preface written on the windswept Spanish island of Furteventura. The island is now mainly a holiday destination, although there is an impressive statue of Unamuno by the main road and also a life size statue of him on a side street.

Found in Essays and soliloquies by Miguel de Unamuno (London: Harrap 1924) this preface written on the windswept Spanish island of Furteventura. The island is now mainly a holiday destination, although there is an impressive statue of Unamuno by the main road and also a life size statue of him on a side street.