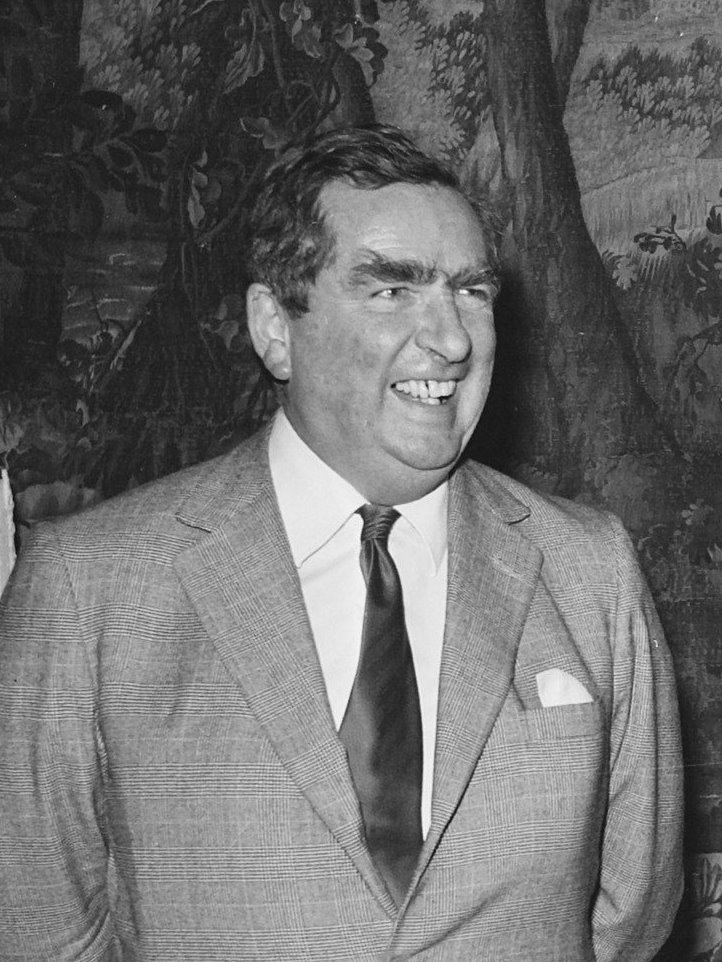

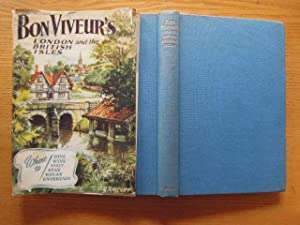

Egon Ronay, along with Raymond Postgate, has become a byword for good food guides in the UK. But did you know that the ‘ Bon Viveur ‘ double act of Phyllis ‘Fanny ‘ Cradock and wine expert husband ‘Johnnie ‘ reported on it with great enthusiasm in their 1955 guide to hotels and restaurants in London and the provinces ?

Here is their report:

‘London’s most food-perfect small restaurant. Two restaurants, in fact, for the price of one. By day this chic rendezvous draws women of international elegance who provide the restaurant with an ever-changing mannequin display as they nibble the now famous brioche toast and drink impeccable coffee in tall glasses. It is, in short, a baby Sacher’s ( from Vienna) , where Viennese and Swiss gateaux compete in popularity with Hungarian Dobos. By night the counters of patisseries and cocktail snacks disappear. Padded banquettes, candlelight and pink tablecloths form background to tranquil dining and the light flickers on climbing plants, the striped, canopied ceiling, the fruit baskets and the impeccable cheese board on the cold table. The Marquee is always filled with couples—romance thrives upon good food and wine. We single out for special commendation the luncheon-time Omelette du Chef with fresh crème and mushrooms (6s 6d) and the Poulet au Riz Sauce Supreme ( 6s. 6d ) plus an excellent table d’hote luncheon for 7s 6d.

In the afternoon the Savoury Gateaux, 2s per slice, is a superlative bonne bouche ; foie gras mousse , mousse of smoked salmon , egg puree and anchovy paste are layered with brioche bread and subtly garnished into gateaux form,

By night Bisque d’Homard (4s 6d) and a magnificent 9s 6d Bouillabaisse lead on to Quenelles de Brochet-the real Quenelles for 7s 6d., a delicate 7s 6d Sole Florentine, Rognons Bange (7s 6d.) with cream and wine, and occasionally a gateaux which is without equal in this town, rather ineptly christened Walnut Souffle Gateaux. But do not bother about its name. Taste it. It is made without any flour at all and is rich in cream and rum. The commendable wines include a light, clean steinwein to marry with fish dishes ( 27s 6d) , ’47 Haut Brion ( Chateau-bottled) 37s. 6d., ’45 Leoville Barton 29s. 6d, and ’49 Vosne Romanee 21s. Amusez-vous bien mes enfants!

Continue reading