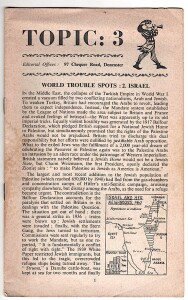

Found among the Joseph O’Donoghue archive at Jot HQ is this copy (pictured) of Topic: 3—a 16 page miscellany dated May 1960 which was possibly aimed at sixth-formers interested in current affairs. It was produced by the husband and wife team who began the still flourishing Mathematical Piemagazine back in 1950.

Why sixth-formers? Well, Mathematical Pie was the brain child of Richard Collins, a Maths teacher at the Gateway School, Leicester, and his wife, and was distributed for a time by the staff of the Mathematics department at the school. Appearing approximately four times a year, it was an entertaining compilation of highly visual mathematical puzzles designed to appeal to children in their early to mid teens. Many of the problems seemed to focus on contemporary issues, such as aviation and space-travel, but clearly the puzzle setters, who included academics as well as schoolteachers, intended to cover as wide a range of subjects as possible.

Early in 1954 Collins and his wife moved to Doncaster—probably to a new school. They continued with Mathematical Pie, but in the late fifties decided to start another magazine with a similar format but this time devoted to teaching a slightly older readership about current affairs. The reasons for this new venture could be many, but judging from the content of Topic: 3, the couple were possibly concerned about the implications of the Cold War, tensions in the Middle East and, perhaps more of interest to schoolchildren, the Space Race, which had become a hot topic by 1960.It is possible that while Collins continued to edit his mathematics magazine, Mrs Collins played a major role in the new venture. We don’t really know, as Topic: 3 doesn’t mention the name of an editor.

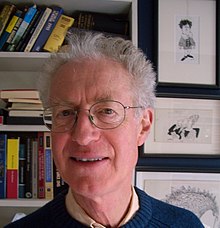

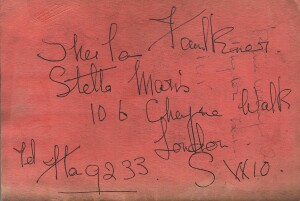

The reason why this particular copy of Topic:3 was found among the O’Donoghue archive can be found on page ten, where an article entitled ‘ Angry Young Men ‘ bears O’Donoghue’s name. By this time the author would have been around 30 years old ( we don’t know exactly when he was born). It would seem that after having been awarded his post-graduate teaching qualification (see earlier Jot) he had begun to teach English, although we don’t know if he was still a schoolteacher in 1960. His analysis of the Angry Young Man trend in contemporary drama and the novel is an astute and well-written appraisal of such writers as Kingsley Amis, John Wain, John Osborne, Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams Colin Wilson and Arnold Wesker. From an examination of the newspaper clippings found in his archive at his death, it is very obvious that O’Donoghue was passionately interested in the movement and shared some of the beliefs held by its protagonists. Continue reading

archive recently, journalist D. B. Wyndham Lewis declared:-

archive recently, journalist D. B. Wyndham Lewis declared:-