The best Champagne

‘,…Short of the best—which some may find an extravagance at eight pounds—it doesn’t make sense to buy champagne. The five pound variety is rarely worth the price. Since competitive alternatives can be had for half as much. From France, the dry sparkling wines of Seyssel are often the equal of medium-priced champagne. California “ champagne” ( the long arm of the French labelling law does not reach across the Atlantic ) can also be quite decent; the best are Korbel Natural and Hans Kornell.

The best college at Oxford

‘Magdalen, both the most beautiful and the most intellectually diverse. Christ Church is an unreconstructed sanctuary of the worst in British snobbery; Balliol is like an American law school, full of politics and ambition. Magdalen has everything : class warfare on even terms, superb tutors, an immense spectrum of interests and tastes’. Other colleges are available…

‘Magdalen, both the most beautiful and the most intellectually diverse. Christ Church is an unreconstructed sanctuary of the worst in British snobbery; Balliol is like an American law school, full of politics and ambition. Magdalen has everything : class warfare on even terms, superb tutors, an immense spectrum of interests and tastes’. Other colleges are available…

The best diet

‘The crashing bore of it all. Everyone knows what the best diet is…Lean meat, cottage cheese. Skim milk, an occasional slice of bread or a baked potato, fresh fruit and veggies; no skipping breakfast, apples and carrot sticks for snacks, plenty of leafy greens to prevent the inevitable…The only thing wrong with the diet—besides the fact that no one in his right mind would stick to it –is that calorie recommendations are too generous, even for the intended audience… Continue reading

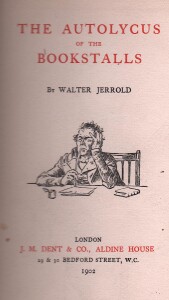

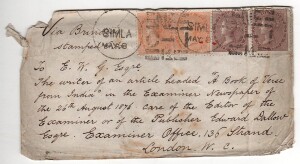

We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner.

We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner. f laughter after hearing that Charles II had been restored to the throne, and the editor of the short-lived magazine The Vole, a pioneering ecological magazine. Boston lived in the same village ( Aldworth ) as Richard Ingrams and was friendly with him. He was also a pal of the artist and writer John Piper ( though Frances Spalding’s biography neglects to mention this fact ) and it was Piper, who may have supported The Vole

f laughter after hearing that Charles II had been restored to the throne, and the editor of the short-lived magazine The Vole, a pioneering ecological magazine. Boston lived in the same village ( Aldworth ) as Richard Ingrams and was friendly with him. He was also a pal of the artist and writer John Piper ( though Frances Spalding’s biography neglects to mention this fact ) and it was Piper, who may have supported The Vole

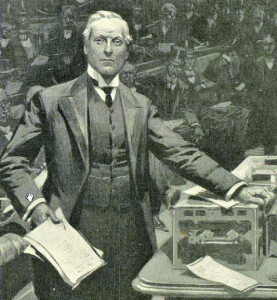

Found among papers at Jot HQ is this carbon copy of an anonymous typescript article on the Liberal Prime Minister H. Herbert Asquith (1852—1928). The author—evidently a Liberal supporter and a great fan of Asquith—reveals various tantalising clues as to his identity, but remains a mystery, despite intensive online research by your constant Jotter.

Found among papers at Jot HQ is this carbon copy of an anonymous typescript article on the Liberal Prime Minister H. Herbert Asquith (1852—1928). The author—evidently a Liberal supporter and a great fan of Asquith—reveals various tantalising clues as to his identity, but remains a mystery, despite intensive online research by your constant Jotter.

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

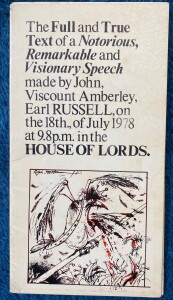

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.

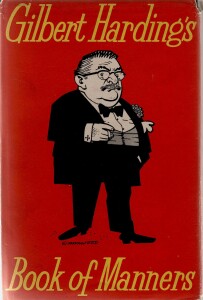

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).