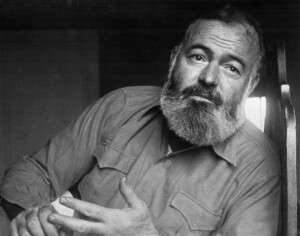

This Jot deals with the final three writers that the bibliomaniac William White collected during his lifetime. Two of them– Emily Dickinson and Nathanael West –were American. Ernest Bramah was British.

Firstly, White admits that his own collection of Dickinson cannot compete with that housed in the Jones Library, Amherst, Massachusetts, her home town. For instance, he only managed to acquire second impressions of the poet’s Poems ( 1890), Poems: second series (1891) and Poems: third series (1896), all of which were brought out by Roberts Brothers of Boston. Today, Abebooks have all three of these first editions at an eye-watering £42,000 the lot. White also owned the first English edition of Poems (1890) which was printed from American sheets of the seventeenth edition with a cancel title page. Today, Abebooks has a copy priced at £2,100.

White declared that the rarest and most expensive of his Dickinson books was a second edition (1915) of The Single Hound: Poems of a Lifetime (1914), which was edited by Dickinson’s niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Abebooks has this first at £1,700.

Ever the scholar, White also felt a need to collect the various biographies of Dickinson, the best of which was George Frisbie Whicher’s This was a Poet ( 1938). One of the principle experts on the poet seems to have been Thomas H. Johnson, whose Poems of Emily Dickinson (1955) and Letters of Emily Dickinson (1958) were praised by White as ‘scholarly productions in every sense of the word’. Mr Johnson also wrote an ‘ excellent ‘ biography.

For some reason White next chose to collect Nathanael West, the novelist who died at just 37 following a car smash and whose best book is possibly Miss Lonelyhearts. According to White, West’s other three novels, The Dream Life of Balso Snell, A Cool Million and The Day of the Locust, were in `1965, being reassessed and accordingly were becoming more sought after, but White managed to buy first editions of them for very reasonable prices. Characteristically, he also felt a need to buy all the reprints, all three of the lives of West and several translations. Today, we might agree with White that West’s appeal is likely to remain ‘limited ‘.

The happy accident that led to White’s decision to collect the works of Ernest Bramah, the English author of the Kai Lung series, was his wife’s discovery of him in anthologies published by Dorothy L, Sayers. Because few Americans knew anything about him, including the Librarian of Wayne State University, White was able to acquire sixteen of the first editions for little more than the $3 he had shelled out for Bramah’s first book—English Farming (1894), which the vendor had catalogued under ‘agriculture’. Continue reading →

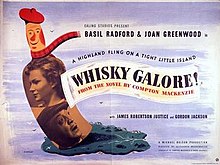

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

Part one

Part one