Found- a thin booklet, the text of a lecture (‘oration’) on idleness  delivered at the London School of Economics in December 1949 by A.H. Smith, the warden of new College Oxford. A.H. Smith (Alic) has a short entry at Wikipedia, his dates are 1883 to 1958. Not one of the famous New College wardens like Maurice Bowra or his predecessor the historian H.A.L. Fisher but known as a philosopher and also as the Vice Chancellor at Oxford. His lecture is on a subject that is still discussed, especially in these hectic, time-poor days. However he refers to his own time as one of fast change, restlessness and impending catastrophe.

delivered at the London School of Economics in December 1949 by A.H. Smith, the warden of new College Oxford. A.H. Smith (Alic) has a short entry at Wikipedia, his dates are 1883 to 1958. Not one of the famous New College wardens like Maurice Bowra or his predecessor the historian H.A.L. Fisher but known as a philosopher and also as the Vice Chancellor at Oxford. His lecture is on a subject that is still discussed, especially in these hectic, time-poor days. However he refers to his own time as one of fast change, restlessness and impending catastrophe.

In 1932 Bertrand Russell had written In Praise of Idleness advocating a three-day week and noting ‘.. immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous’, earlier Kierkegaard had written’..far from idleness as being the root of all evil, it is rather the only true good.’ In our time the industrious Tom Hodgkinson published How to Be Idle: A Loafer’s Manifesto and founded (or revived) The Idler. Smith states that by idleness he does not mean being a total slacker or waster, also he does not mean playing lots of sport, joining multiple student societies and general not studying. He is an advocate of strenuous study but of knowing when to stop, not overdoing it ‘… when you close your books, close them with a bang, and abandon yourself to the enjoyment of idleness..’ Continue reading

Found –Life (Dent, London 1921) a

Found –Life (Dent, London 1921) a

Most of the Common-Place books you find in auctions or second-hand bookshops date from the nineteenth century—usually before about 1860—and are dull, dull, dull! They invariably contain passages from history books, books of sermons, and extracts from poems by Felicia Hemans and Robert Southey. Often they are illustrated by amateurs who like to think they can draw. Occasionally there are exceptions to this rule, but these rarely surface. So it’s nice in this Age of the Internet to find a Common –Place book that contains some information that is not always easy to find using Google. Such is the volume that we at Jot HQ discovered in a box of ephemera the other day.

Most of the Common-Place books you find in auctions or second-hand bookshops date from the nineteenth century—usually before about 1860—and are dull, dull, dull! They invariably contain passages from history books, books of sermons, and extracts from poems by Felicia Hemans and Robert Southey. Often they are illustrated by amateurs who like to think they can draw. Occasionally there are exceptions to this rule, but these rarely surface. So it’s nice in this Age of the Internet to find a Common –Place book that contains some information that is not always easy to find using Google. Such is the volume that we at Jot HQ discovered in a box of ephemera the other day.

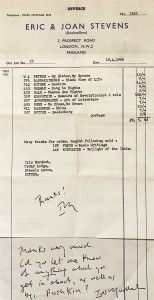

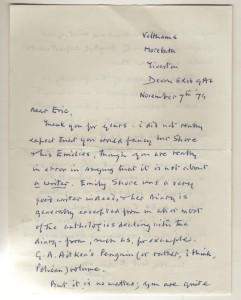

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

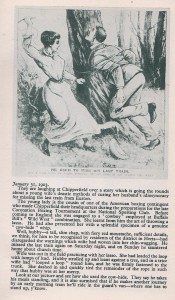

Found among a pile of newspaper clippings at Jot HQ is this substantial analysis in the 2 December 1935 issue of the Financial Timesof the thriving bicycle industry.

Found among a pile of newspaper clippings at Jot HQ is this substantial analysis in the 2 December 1935 issue of the Financial Timesof the thriving bicycle industry.