The journalist George Hutchinson (see previous Jots) was living in wartime Bradford when he visited High Withens, the supposed ‘ dwelling ‘ of Mr Heathcliffe of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Up on the lonely moors Hutchinson finds it hard to recognise that ‘England is at war’,

The journalist George Hutchinson (see previous Jots) was living in wartime Bradford when he visited High Withens, the supposed ‘ dwelling ‘ of Mr Heathcliffe of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Up on the lonely moors Hutchinson finds it hard to recognise that ‘England is at war’,

‘ Indeed, though the only indication in the whole locality is the scores of little evacuees and mothers, mostly from Bradford. The moor air and country rambles they have exchanged for city life should be of lasting benefit to these children and to many a mother, I am told, the rural beauty so near to Bradford has been quite a revelation—which in itself is salutary.’

Doubtless, in these days of local lockdowns, such salubrious open-air refuges from unhealthy urban landscapes, are appreciated for different reasons.

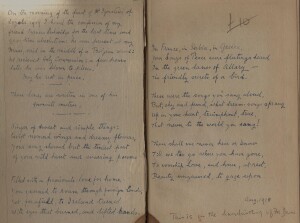

Hutchinson had already visited the Bronte Waterfall, not far from the Haworth Parsonage and this was not his first visit to Stanbury, the nearest village to High (or top) Withens, which he had never managed to reach before. On the way there he popped in to see the famous Jonas Bradley, former Head of Stanbury School and an international Bronte expert, at his home, Horton Croft in the village. Here he was invited to sign, not for the first time:

‘the third of the visitors’ books that Mr Bradley has kept since 1904. These books contain thousands of signatures, and his callers, they will tell you, have come from places as far apart as Glasgow and Godalming, Bulawayo and Brooklyn…’

This was probably the last time that Hutchinson saw Bradley, for he died early in 1943, aged 84, his obituary appearing that year in volume 10 of the Transactions of the Bronte Society, which he had helped to found many decades before. In this obituary Bradley’s reputation worldwide as a Bronte expert was confirmed. He had indeed been visited by ‘American University professors, statesmen, film directors and writers..’ Continue reading

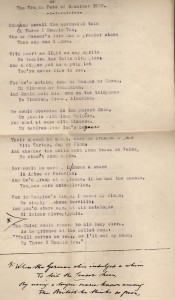

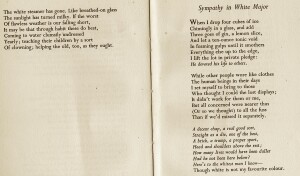

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

It’s always revealing to learn which books were the favourites of certain writers—and which books or writers were reviled. We know what Wyndham Lewis felt about the Bloomsbury set. It’s all in The Apes of God. It’s not a secret that Martin Amis worships Nabokov and Saul Bellow or that Kingsley Amis was a Janeite. The likes and dislikes of pre-modernist writers, however, tend to be less well known today, so it’s good to find someone expressing their secret admiration for a certain writer or a certain passage of prose or poetry.

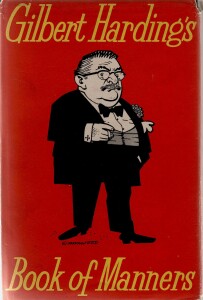

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books. Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.

Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.

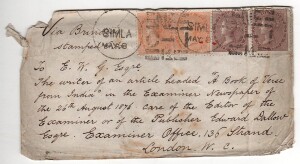

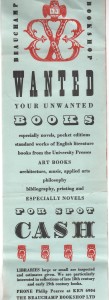

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.