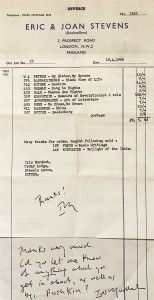

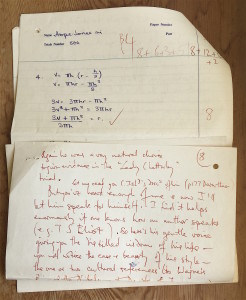

Found – a receipt from the late booksellers Eric and Joan Stevens for books sold to the novelist Iris Murdoch in 1966. There is also a request in her hand for anything by, or on, Pushkin. Iris Murdoch was very keen on Russian literature, especially Dostoyevsky, but she did not write about Pushkin – although her husband John Bayley wrote Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary which was published in 1971. This request may have been for him.

Found – a receipt from the late booksellers Eric and Joan Stevens for books sold to the novelist Iris Murdoch in 1966. There is also a request in her hand for anything by, or on, Pushkin. Iris Murdoch was very keen on Russian literature, especially Dostoyevsky, but she did not write about Pushkin – although her husband John Bayley wrote Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary which was published in 1971. This request may have been for him.

Her order is certainly eclectic- some religious, even mystical work, (Radhakrishnan and Swedenborg), a geezerish prison memoir, not at all her style – Frank Norman’s Bang to Rights and a book on the Samurai (‘Bushido’). Peter’s My Sister, My Spouse is about Lou Andreas Salome ‘A Biography of the Woman Who Inspired Freud’ (also Nietzsche and Rilke) – an important and much loved writer and psychiatrist. Penn’s No Cross, No Crown is William Penn’s work on Primitive Christianity from 1669, probably not a first edition at 10 shillings, although the Stevens were always very reasonable in their pricing.

Other works ordered include a Baedeker for the Rhine, possibly for a holiday. It its still fun to visit Europe with an old Baedeker. Schopenhauer is dealt with fairly well in her later work Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. Kropotkin fits in with her interest in Russian life and literature. Hale’s Famous Sea Fights is a mystery, possibly light reading or a present for a friend.

The Stevens’ had other famous writers as clients, including Anita Brookner and Geoffrey Hill, from whom they also bought many books. Iris Murdoch’s considerable library eventually went into the book trade, but not to Eric and Joan.

Found – a 1982 book collector’s catalogue from George S Macmanus of Philadelphia 500 Books with Interesting Inscriptions. Mostly modern American and British literature, it has many direct signed presentation from the authors and many

Found – a 1982 book collector’s catalogue from George S Macmanus of Philadelphia 500 Books with Interesting Inscriptions. Mostly modern American and British literature, it has many direct signed presentation from the authors and many

Found among the papers of the mathematician

Found among the papers of the mathematician