Found in a pile of books here at Jot HQ—a paperback copy dated 1943 of Agatha Christie’s Poirot Investigates. It’s exactly the same size as a Penguin, but was in fact published for the British Publishers Guild by John Lane at The Bodley Head. These ‘Guild Books’ were originally designed to rival Penguins, which were dominating the paperback market at the time. However, they never proved as popular and the Guild later folded.

But this particular Guild Book is different from most others in the series in that the original covers have been removed and replaced by what appears to be brown salvaged card. There is a panel for the title which is rubber-stamped, underneath which is a triangle bearing the legend ‘ EVERYBODY’S REBOUND’ 1/6. There then follows an explanation of what ‘Everybody’s Rebound was trying to achieve.

This is a rebound copy of a book worth reading published by a well-know publisher.

We are rebinding books such as this, in order that as many books as possible may do their job twice and so help the vital “ Save Paper “ Campaign.

If you have any books of any kind, and in any condition, that you can spare send or bring them to us and we will make you the highest cash offer.

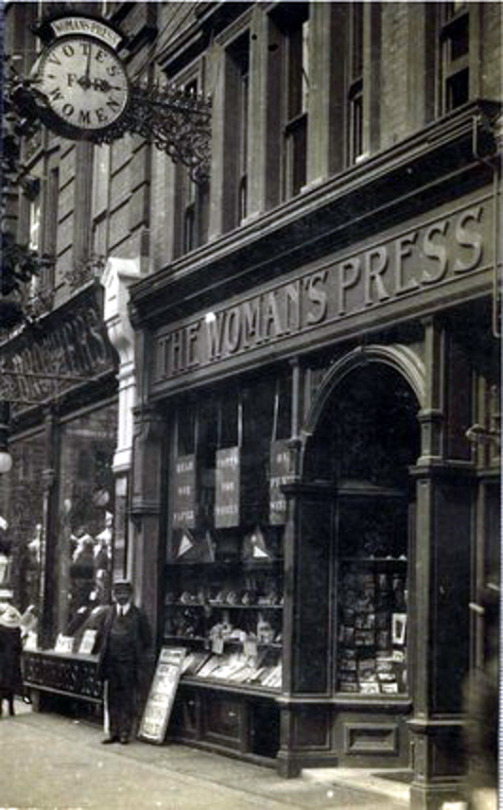

EVERYBODY’S BOOKS

156, Charing Cross Road, W.C.2.

It is questionable whether this or any other book ‘rebound ‘ by Everybody’s Books was ‘ worth reading ‘. What is not in dispute is the merit of salvaging paper at a time of shortage. The thinking seems to have been that at a time when reading was an important way of distracting people from the War ( after all, the sales of poetry went sky high during the conflict), any means of giving damaged paperbacks a new lease of life was worth doing. Better to rebind a coverless book than print a new edition using paper which was a scarce resource. What was not revealed was whether hardbacks without covers could be saved in the same way. Nor was there any indication as to when this Guild Book was rebound. An inscription on the inside cover shows that a certain Ann Seabrook owned the book in September 1948, and as paper salvage continued until 1950, the rebinding may have occurred around 1948.

Continue reading