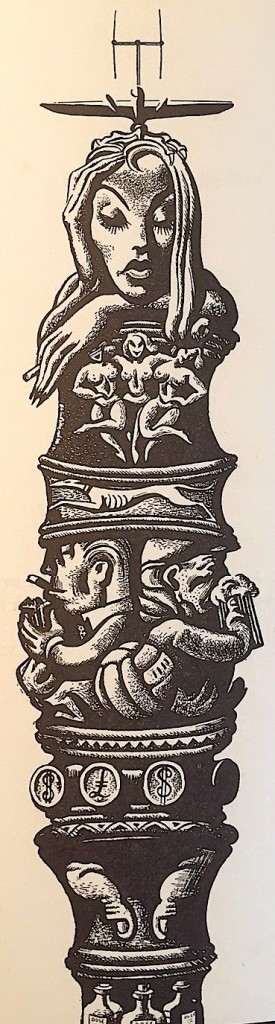

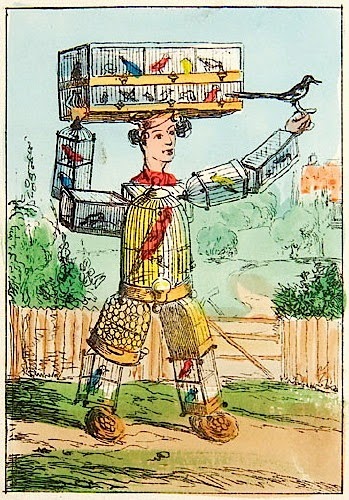

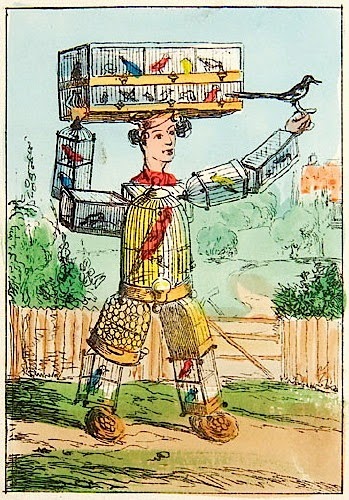

Found - in London Cries Illustrated for the Young (Darton & Co, London, circa 1860). 11 charming hand-coloured plates depicting street vendors each composed of their wares, i.e. the brush maker is made of brushes and the image seller, above, is made of prints and images. A rather rare collectable juvenile book of some value. Marjorie Moon's slightly used copy sold at Bloomsbury Auctions in London for £500 in 2005. The text is aimed at quite young persons - for the image seller it reads thus:

Poor Pedro! what a strange load he bears! He has become one mass of images from top to toe. Well may he cry "images", in hopes that some one will ease him of his burden. They are very cheap. There is the head of Shakespeare, and of our gracious Queen; Tam o'Shanter and Souter Johnnie; Napoleon, parrots and I know not what besides, all made out of plaster of Paris, by poor Pedro in his little attic, which serves him for bed-chamber, sitting room and workshop. Have you ever seen these poor Italians at their work? I have, and very poorly are they lodged and fed, I can assure you. One would wonder what can make them leave their sunny Italy, where fruits hang thick as leaves upon the tress, to come and toil in darkness and dirt in our narrowest streets. But I suppose they little know what London is till they are settled down with very distant prospect of return. They hear of it as famous city, paved with gold - that is the old story, you know - where every one can make his fortune; and they come to try. Poor Pedro, he had a happy home once, too; but a terrible earthquake shook that part of Naples which contained his little hut. The earth shook so violently that houses and walls tottered and fell, nay, in many parts whole streets not only fell but were swallowed up by the gaping earth, which opens at these times just like a hungry mouth, and closes again over all that falls in.

|

| The Seller of Songbirds |

It was in the night this earthquake came; and Pedro, than a little boy, was roused by the cries of his father and mother, who felt their house shaking round them. Out into the open air they all rushed, with nothing but a few clothes they had on. The streets were full of people, who knelt and prayed aloud to God to spare their lives. The bells in all the churches clashed wildly, as the towers rocked to and fro. It was a dreadful day, and Pedro will never forget it. By morning many of the houses were buried in the earth, and others lay in heaps of ruin on the ground. Amongst these was the poor hut of Pedro's father. It has been a shabby little home, but still it was their home and held all their wordily goods, and sorely they wept over it destruction. The little garden, too, was all laid waste. Some kind people gave money to build up once more the ruined houses; but, whilst this was being done, there was sore want and famine, and many left their native lace to try their fortunes elsewhere. And so it was that Pedro came, with many more, to earn his living by selling images in London streets.