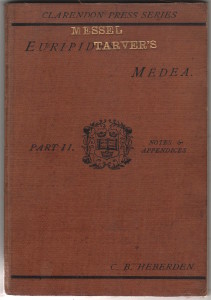

Found in a box of old text books (Zinn collection) is this copy of part two of C. B. Heberden’s edition of Euripedes’ Medea ( notes and appendices) published by the Clarendon Press in 1886.Stamped in gold lettering on the light brown cover of this distinctly dull-looking school text book are the words MESSEL/TARVERS. Inscribed in pencil on the fly-leaf we find ‘ L.Messel/Tarvers ‘, which suggests that it belonged at one time to Leonard Charles Rudolph Messel ( 1872 – 1953), father of the famous stage designer Oliver Messel. Beneath the inscription are two pencil and ink drawings—one of a veiled lady in Victorian dress, the other a small profile of a man’s head.

Found in a box of old text books (Zinn collection) is this copy of part two of C. B. Heberden’s edition of Euripedes’ Medea ( notes and appendices) published by the Clarendon Press in 1886.Stamped in gold lettering on the light brown cover of this distinctly dull-looking school text book are the words MESSEL/TARVERS. Inscribed in pencil on the fly-leaf we find ‘ L.Messel/Tarvers ‘, which suggests that it belonged at one time to Leonard Charles Rudolph Messel ( 1872 – 1953), father of the famous stage designer Oliver Messel. Beneath the inscription are two pencil and ink drawings—one of a veiled lady in Victorian dress, the other a small profile of a man’s head.

Leonard was the eldest son of Ludwig Messel, a German stockbroker who had emigrated to Britain, possibly in the late 1860s.He married and in 1890 bought Nymans, a 600 acre estate near Hayward’s Heath in West Sussex. His son Leonard was sent to Eton, where he joined Tarver’s house, and that is all we really know about his life as a schoolboy. However, if he did execute the two drawings, then he obviously passed on his artistic skills to his son Oliver, who may also have inherited skills from his mother, who was the daughter of Edward Linley Sambourne, the eminent Punch cartoonist. This being so, it is equally likely that Oliver, who also attended Eton, inherited his father’s copy of Heberden’s Euripides, and it was he who drew the veiled woman and male profile. Continue reading

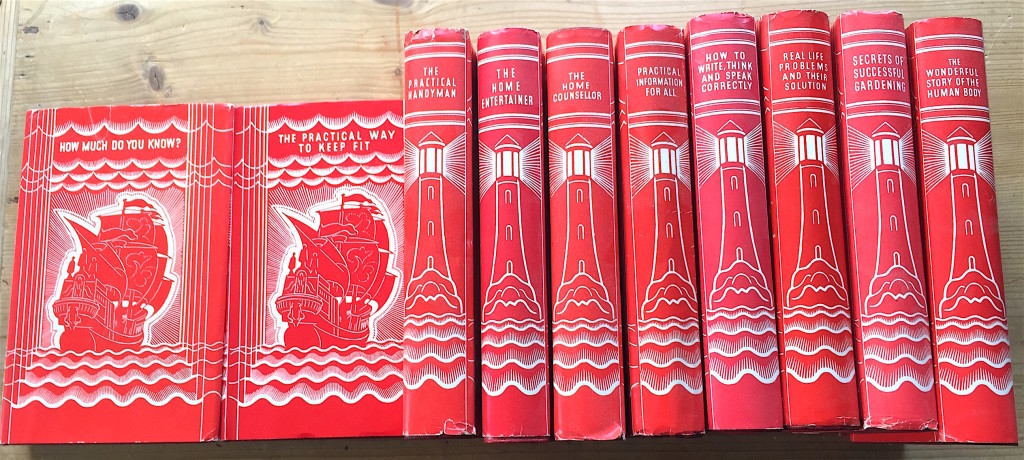

Found- a bookmark advertising the virtues of Everyman’s Encyclopaedia. For obvious reasons the set is now of very little value, except as decoration. In the 1920s, when these were written it was a (relatively) portable fount of all knowledge – hence these brief encomiums from the great and the good (and the titled). Sets could be bought with their own small book-case ‘in unstained oak’ and the deluxe versions in full leather (£7 10 shillings.) It boasted 7 million words and 2700 illustrations plus a World Atlas.

Found- a bookmark advertising the virtues of Everyman’s Encyclopaedia. For obvious reasons the set is now of very little value, except as decoration. In the 1920s, when these were written it was a (relatively) portable fount of all knowledge – hence these brief encomiums from the great and the good (and the titled). Sets could be bought with their own small book-case ‘in unstained oak’ and the deluxe versions in full leather (£7 10 shillings.) It boasted 7 million words and 2700 illustrations plus a World Atlas.