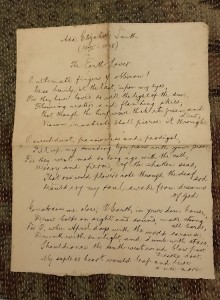

Found in a book published by J.R. Tutin, the Hull based reprinter of 17th century literature, a short letter from 1908 to John Haines, a Gloucestershire solicitor and minor poet associated with Ivor Gurney, F.W. Harvey, Edward Thomas and other members of the Dymock Poets group. After discussing various Elizabethan writers Tutin wrote out a fine poem by Ada Elizabeth Smith (1875- 1898) called ‘The Earth Lover’. He had found it in a recent anthology New Songs put together by F Y Bowles – ‘the poem is a real gem in my opinion : yet I’ve not seen it noticed by in any of the reviews of the book.’ A search online reveals little about Ada Elizabeth Smith, a classic poete maudit, except this anonymous (‘J.L.G.’) quite high-flown notice in the London based literary magazine The Academy of December 1898 a week after her untimely death.

Found in a book published by J.R. Tutin, the Hull based reprinter of 17th century literature, a short letter from 1908 to John Haines, a Gloucestershire solicitor and minor poet associated with Ivor Gurney, F.W. Harvey, Edward Thomas and other members of the Dymock Poets group. After discussing various Elizabethan writers Tutin wrote out a fine poem by Ada Elizabeth Smith (1875- 1898) called ‘The Earth Lover’. He had found it in a recent anthology New Songs put together by F Y Bowles – ‘the poem is a real gem in my opinion : yet I’ve not seen it noticed by in any of the reviews of the book.’ A search online reveals little about Ada Elizabeth Smith, a classic poete maudit, except this anonymous (‘J.L.G.’) quite high-flown notice in the London based literary magazine The Academy of December 1898 a week after her untimely death.

Early Dead. Ada Smith 1875 – 1898 In Memoriam. 17 – 12 – 98

Ada Smith was born in Haltwhistle, a hard featured village from which a bare land runs up to the bleak escarpments that carry the ruined line of the Roman wall. She began early to write verse, and published at 13, having acquired very easily a versification of noticeable grace, smoothness, and cadence. She spent some years abroad, chiefly at Vienna and went about with adventurous and observant audacity. Her idea was that she must not only study life as it met her, but seek it out in the hope of writing novels in the coming time. At this period some of the work found its way into the hands of the present writer. It had too many words and not enough pauses and there was much feigning of the Heinesque. Without being quite able to see what she might arrive at, one felt she must go on.

She returned from Vienna last year with the feeling that she was at last equipped for London, and the great adventure could not be delayed. She attempted London at the age of 22 with a nerve wilful and steady. She did not fail. Verses began to be accepted, and her work matured rapidly. She did typewriting, and it must have been hateful.. Her constitution suddenly began to give way in the summer. A long holiday upon the Northumbrian coast made her better, but not well. She ought not to have gone back to typewriting in the city, but she would and did. A couple of months ago she had to return to the North for the last time quite broken down. Her illness ultimately developed in the gravest way then advanced with frightful rapidity. She died at Newcastle upon Tyne upon the Wednesday night of last week.

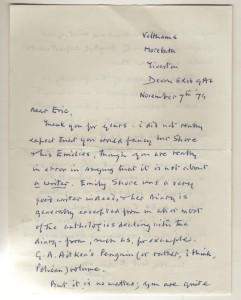

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University. If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

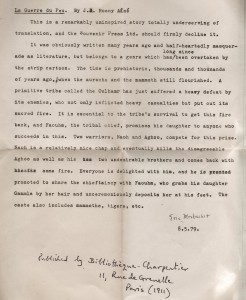

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

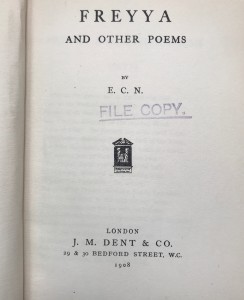

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

Found in The Album for August 19th, 1895, are these encouraging words for aspiring fiction writers:-

Found in The Album for August 19th, 1895, are these encouraging words for aspiring fiction writers:-