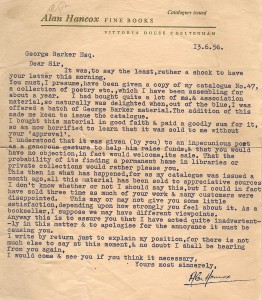

PHILIP LARKIN. ( The Times Educational Supplement, July 13th 1956)

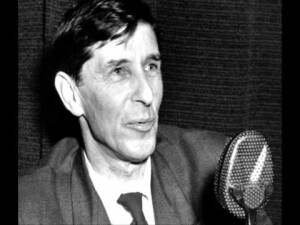

It’s just over a century since Philip Larkin was born. Quite rightly, since he is a major poet, radio and TV have been crowded with tributes—four programmes in one evening a couple of weeks ago—and reassessments on Radio 4 from the man who now holds the post that Larkin politely declined—Simon Armitage, the Poet Laureate. There have doubtless been meetings of Larkin enthusiasts around the country and in May one major symposium ( which your Jotter attended) held by The Larkin Society in Hull as part of an Alliance of the Lit erary Societies weekend.

erary Societies weekend.

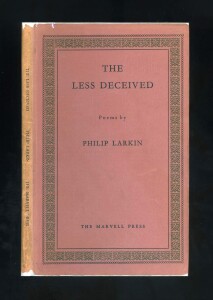

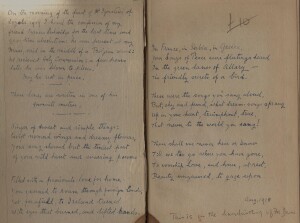

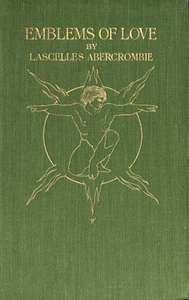

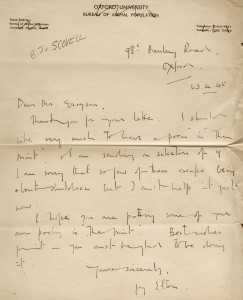

So the legacy of Larkin is very much in the minds of poetry lovers at the moment and luckily for us, the literary archive left behind by the former academic Patrick O’ Donoghue , contains two clippings —one anonymous portrait in the Times Educational Supplement of the poet following the publication of his first major collection, The Less Deceived—and a full review by D .J. Enright of his second slim volume, The Whitsun Weddings.

This first Larkin Jot considers the TES profile. Here, the anonymous profiler describes him as ‘ one of the most successful poets of his generation’ , which seems a slight exaggeration, since following the underwhelming The North Ship of 1946 he had only published a privately printed pamphlet XX Poems in 1951, which ( like Auden with his privately printed Poems of 1928) he sent free copies of to ‘ most of the leading figures of this country’, and a thin Fantasy Press pamphlet in 1954. Both are now hard to come by.It is true that The Less Deceived had run into three editions within nine months, but can this one success make him ‘ one of the most successful poets of his generation ‘? Mind you, two possible rivals, Kingsley Amis and Donald Davie ( remember him?) who were also born in 1922, could hardly be described as ‘ successful ‘, if successful means popular and highly regarded by 1955. Charles Causley and ( ) might have been rivals, though.

Be that as it may, the profiler is surely correct in describing The Less Deceived as

‘ as sharp an expression of contemporary thought and experience as anything written in our time, as immediate in its appeal as the lyric poetry of an earlier day, it may well be regarded by posterity as a poetic monument that marks the triumph of clarity over the formless mystification of the last 20 years ‘.

Larkin is credited with bringing poetry back to the ‘middle-brow public’. It would be nice to know who this anonymous profiler was, for surely the immediate success of The Less Deceived was partly due to a reaction by the poetry-buying public to the mystification wrought by the Apocalypse school of Nicholas Moore, Henry Treece al and the abomination that was The White Horseman. The Movemnet was partially a reaction to this obscurantism , but Larkin was never really part of it. He did not contribute to such a periodical as New Lines, but he was doubtless in sympathy with its aim.

What comes across strongly in the profile is Larkin’s resignation to his lot as a career librarian who writes poetry in his spare time but who is not an amateur. Continue reading

If you search for ‘Paul Lester’ online most the results will concern Paul Lester, the prolific rock critic and biographer; but anyone interested in performance poetry over the past 45 years will hopefully ignore these references and refine their search by adding ‘ poet ‘ or ‘Birmingham’ to ‘ Paul Lester’. They could also add ‘Protean ‘. For ever since Lester published his first poetry pamphlet in 1975 he has been regularly issuing slim volumes ( some very slim) , usually under his own imprint, Protean Publications, from an address in Knowle, near Solihull, although he actually lives in Rubery, in the far south-west edge of Birmingham.

If you search for ‘Paul Lester’ online most the results will concern Paul Lester, the prolific rock critic and biographer; but anyone interested in performance poetry over the past 45 years will hopefully ignore these references and refine their search by adding ‘ poet ‘ or ‘Birmingham’ to ‘ Paul Lester’. They could also add ‘Protean ‘. For ever since Lester published his first poetry pamphlet in 1975 he has been regularly issuing slim volumes ( some very slim) , usually under his own imprint, Protean Publications, from an address in Knowle, near Solihull, although he actually lives in Rubery, in the far south-west edge of Birmingham.

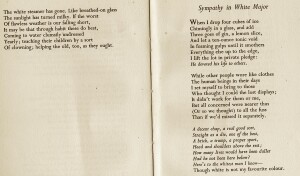

In the April 24th 1942 issue of John O’London’s Weekly can be found a perceptive view by the essayist Robert Lynd on the subject of risible poetry written by good poets. He takes his cue from an incident a century before when Thomas Wakley, the founder of the Lancet, stood up in the Commons to mock some puerile lines from ‘Louisa’ by the Poet Laureate, William Wordsworth.

In the April 24th 1942 issue of John O’London’s Weekly can be found a perceptive view by the essayist Robert Lynd on the subject of risible poetry written by good poets. He takes his cue from an incident a century before when Thomas Wakley, the founder of the Lancet, stood up in the Commons to mock some puerile lines from ‘Louisa’ by the Poet Laureate, William Wordsworth.

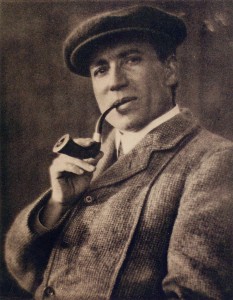

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes: