Found- a press cutting from The Bookman, March 1932 by one De V. Payen-Payne, a good evaluation of the life and work of C. K. Scott Moncrieff – in a review of a posthumous book by him. It may be a myth or an exaggeration but I heard that Scott-Moncrieff was working on his monumental Proust translation while on the staff at The Times and occasionally when he was stuck for the English mot juste (as it were) he would consult the entire office and everything came to a halt while the right word was found – world news be damned!

Painting of Scott Moncrieff by E S Mercer

It is a moot point whether a mother or a wife or any near relative can write the ideal biography. Not that this book pretends to be a biography, although it contains many details that only a mother can give, and will prove invaluable when the ideal biographer appears, and Scott Moncrieff’s work is assessed critically and compared with the lit he led. Some may think that too much space has been given to his experiences in the War and to the letters that he wrote to his family and friends when on service. Since 1918 we have a large number of such accounts, and Scott Moncrieff’s adventures, although most creditable to himself, were not very different from those of many other intellectual men thrown into the cortex of combat. Others too may think that the postscript is too personal for inclusion. Instead of it, an index would have been a desirable adjustment. Continue reading

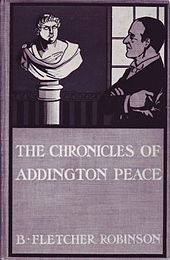

Found in a thriller by

Found in a thriller by

We all know about the nerds who post online corrections to errors or omissions in books, films, dramatisations and the like. Well back in 1987 , before the Internet made it all too easy, there were people like R. Lujer, who typed their complaints to—in this case—the publisher of Peter Haining’s The Television Sherlock Holmes. Haining, who was doubtless royally entertained by this particular letter, kept it in his Archive. Here it is in full.

We all know about the nerds who post online corrections to errors or omissions in books, films, dramatisations and the like. Well back in 1987 , before the Internet made it all too easy, there were people like R. Lujer, who typed their complaints to—in this case—the publisher of Peter Haining’s The Television Sherlock Holmes. Haining, who was doubtless royally entertained by this particular letter, kept it in his Archive. Here it is in full.

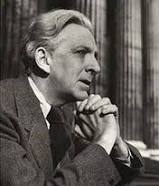

Listing British novelists or poets who were also medics is a fun party game. Going right back to the eighteenth century one can think of Goldsmith and Smollett. From the nineteenth, I suppose Keats can be included, although without a degree in medicine, he can’t be classed as a physician. Thomas Lovell Beddoes is a less well known example, as is Samuel Warren, who ought to be better known, especially as his ground-breaking Passages from the Diary of a late Physician heavily influenced the Bronte sisters. Among the twentieth century poets there are a few, including Dannie Abse and Alex Comfort and I dare say one or two writers studied medicine, but never practised it. I don’t think Somerset Maugham did, apart from a stint in the Red Cross. And then there is Gabriel Fielding (1916 – 86).He certainly practised. In fact he was a GP and a prison doctor based in Maidstone for many years until literary fame allowed him to give up medicine and try his luck in America. With a mother who was a descendant of Henry Fielding, he certainly possessed the literary credentials to succeed, and indeed he did, but not so much in his native land, where he is still little known. The reputation of Alan Gabriel Barnsley (his real name) is well documented in a review dated April 6th 1963 from the Haining Archive. In it, John Horder, himself a doctor and writer, marks the publication of Fielding’s fourth novel, The Birthday King, which had just appeared in the States, with the statement that in America he was acknowledged as ‘ one of our leading novelists, along with Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Iris Murdoch’. According to Horder, Gabriel’s obsession with ‘the darkness in man ‘ was present from the start. In his debut novel, Brotherly Love (1954), for instance, Fielding’s hero, David Blaydon, who is based on the author’s eldest brother George, gets pushed into the Church, becomes entangled in the lives of various women in his parish and eventually falls ‘a great height from a tree to be found dead by one of his brothers in one of the most horrifying scenes in fiction’.

Listing British novelists or poets who were also medics is a fun party game. Going right back to the eighteenth century one can think of Goldsmith and Smollett. From the nineteenth, I suppose Keats can be included, although without a degree in medicine, he can’t be classed as a physician. Thomas Lovell Beddoes is a less well known example, as is Samuel Warren, who ought to be better known, especially as his ground-breaking Passages from the Diary of a late Physician heavily influenced the Bronte sisters. Among the twentieth century poets there are a few, including Dannie Abse and Alex Comfort and I dare say one or two writers studied medicine, but never practised it. I don’t think Somerset Maugham did, apart from a stint in the Red Cross. And then there is Gabriel Fielding (1916 – 86).He certainly practised. In fact he was a GP and a prison doctor based in Maidstone for many years until literary fame allowed him to give up medicine and try his luck in America. With a mother who was a descendant of Henry Fielding, he certainly possessed the literary credentials to succeed, and indeed he did, but not so much in his native land, where he is still little known. The reputation of Alan Gabriel Barnsley (his real name) is well documented in a review dated April 6th 1963 from the Haining Archive. In it, John Horder, himself a doctor and writer, marks the publication of Fielding’s fourth novel, The Birthday King, which had just appeared in the States, with the statement that in America he was acknowledged as ‘ one of our leading novelists, along with Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Iris Murdoch’. According to Horder, Gabriel’s obsession with ‘the darkness in man ‘ was present from the start. In his debut novel, Brotherly Love (1954), for instance, Fielding’s hero, David Blaydon, who is based on the author’s eldest brother George, gets pushed into the Church, becomes entangled in the lives of various women in his parish and eventually falls ‘a great height from a tree to be found dead by one of his brothers in one of the most horrifying scenes in fiction’.

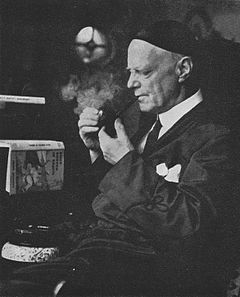

Found in Essays and soliloquies by Miguel de Unamuno (London: Harrap 1924) this preface written on the windswept Spanish island of Furteventura. The island is now mainly a holiday destination, although there is an impressive statue of Unamuno by the main road and also a life size statue of him on a side street.

Found in Essays and soliloquies by Miguel de Unamuno (London: Harrap 1924) this preface written on the windswept Spanish island of Furteventura. The island is now mainly a holiday destination, although there is an impressive statue of Unamuno by the main road and also a life size statue of him on a side street.

Found – the typescript of a review by

Found – the typescript of a review by