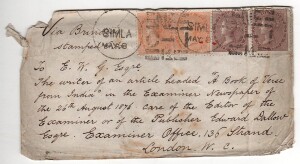

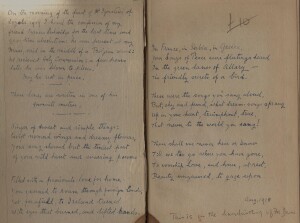

Found interleaved in a copy of The Life and Letters of Sir Edmund Gosse by Evan Charteris (1931) at Jot HQ is an empty envelope addressed to Gosse postmarked Simla May 8th1878. At the top of the envelope the sender has written ‘via Brindisi ‘.

A message that occupies the rest of the envelope follows thus:

‘ To E.W.G Esq. The writer of an article headed “ A Book of Verse from India “ in the Examiner Newspaper of the 26thAugust 1876 care of the Editor of the Examiner or of the Publisher Edward Dallow Esqre. Examiner Office. 135 Strand, London W.C.

What ostensibly seems to throw up problems of identification turns out, thanks to a little online research, a significant document in the history of Anglo-Indian literature. All the clues needed to identify the sender of the letter (alas missing) can be found on the cover of its envelope. Firstly E.W.G. is obviously Edmund Gosse, although at the time the letter-writer knew him only by his initials, the custom at the time being for some reviewers only to use the first letters of their names. The review in question appeared in The Examiner, a literary newspaper that had been founded by the poet, critic and friend of John Keats, Leigh Hunt in 1808. By the time Gosse was writing for it this once radical journal has lost its bite, but the fact that it was willing to allot space to a debut collection by an unknown young writer from Calcutta brought out by a small publisher in the city without preface or introduction, suggests that it recognised genuine talent.

And this poet deserved to be recognised. Toru Dutt was the highly educated daughter of a leading Government official from Calcutta and she was just twenty when A Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields appeared. We don’t exactly know how such an obscure volume appeared on Gosse’s desk in London, but it is highly likely that Toru’s proud father, Govin Chandra Dutt, himself a linguist and a poet, was both responsible for sending the book to the Examiner and writing the letter to Gosse. If not her father, it may have been her mother, a talented interpreter, or her translator sister, who wrote the letter. All were aware of Toru’s prodigious literary gifts. We do not know the significance of ‘via Brindisi ‘ inscribed on the envelope. Continue reading

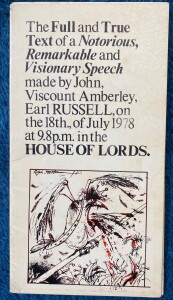

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.

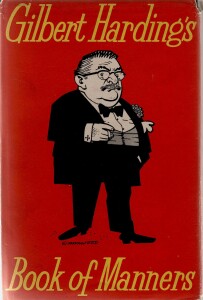

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).

The recent sudden fall from grace of Tudor historian and broadcaster David Starkey over his remarks on the Black Lives Matter campaign recalls to mind another broadcaster of an earlier decade whose detractors also dubbed him ‘ the rudest man in Britain’—Gilbert Harding. This shared reputation comes to mind as we discovered a copy at Jot HQ of the very funny and often wise treatise on good behaviour, Gilbert Harding’s Book of Manners(1956).

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.

Over the years New Towns have received a bad press. They are regarded as too large and unwieldy in contrast to small, more intimate developments, such as Prince Charles’ Poundbury ( called by some Poundland) in Dorset and Cambourne in Cambridgshire. The last major New Town in England was probably Milton Keynes, which was begun in the sixties and took its inspiration from Stevenage New Town.