Sheekey’s

‘Fanny ‘ and Johnnie Cradock evidently enjoyed seafood and were fussy about how it was cooked and served. They particularly hated oyster stew that had been ‘stewed indefinitely’. Here is their entry on the fish restaurant Sheekey’s, which is still there in St Martin’s Court, Covent Garden, seventy years on, though operating on a much larger scale as J. Sheekey .

Nell is still there, still opening oysters superbly and still warming us with her bright smile and flashing cockney humour.

This restaurant could scarcely be plainer. It is a small scrubbed temple dedicated to fresh fish, so pray do not hold us culpable if you accept our recommendation: ask for two lamb cutlets, a salad and some spinach and then moan, ‘ but dahling, I loathe fish’. Stay away, if you cannot enjoy a wedge of fresh turbot (5s.), pink, wet crab and lobster salads (7s), Scotch salmon in season (8s 6d), oyster stew which is not stewed indefinitely ! a heinous offence! And a dozen oysters, which in season are the pick of the Whitstable and Ham Oyster Beds daily dredge.

Rejoice, too, that you can purchase those sound fishy partners, Hock and Chablis by the glass for 4s., or fly higher if you prefer with one of several varieties of sound, dry champagne. Additionally, after the oysters, Frances dotes upon the big jugs of crisp celery, the tin brown bread and butter, the Stilton, or Wensleydale, and the good black coffee thereafter. A perfect meal for under a pound—without wines—and one of the most nourishing and sustaining that we know.

Proprietors: Mr and Mrs Williams

Questions remain regarding the history of Sheekey’s. The restaurant’s website is good on marketing the place, but not so informative on its history. Considering the restaurant is so proud of its long history, one might expect considerable detail on how it reached its present reputation. Instead all we get are a few words on its humble origins as a roadside seafood stall. One would like to know, for instance, who the fabled ‘Nell ‘was, or who were Mr and Mrs Williams, the owners in 1955. Presumably, like many other restaurants of note, this couple liked to conjure up a feeling of nostalgia for the ‘good old times ‘by retaining the name of the first owner. But was it necessary to change the perfectly acceptable Sheekey’s to J. Sheekey?

Anyway, things have changed a lot since the Cradock’s visited the place. Long gone, not surprisingly, is the ‘perfect meal for under a pound ‘. Today it is reckoned that diners would get little change from £100 for an a la carte meal. As for the set lunch (Sun – Friday, 12 – 4.45 pm), two very modest courses ( no oysters here) would set you back £33. As for oysters, the cheapest come at six for £27 and the most expensive ( Loch Ryan ) at six for £39. Back in 1955 you were offered ‘ the pick of the Whitstable and Ham Oyster Beds. But there is no mention of these famous beds in today’s menu.

The mains fish dishes are frankly expensive (‘overpriced for what you get’, as one displeased diner put it on Trip Advisor ). Compare the 1955 turbot at 5s. with the 2024 roasted fillet of cod at £36, or the 1955 ‘ Scotch salmon ‘ at 8s 6d with the 2024 miso salmon at £34. But that’s inflation I suppose! Nor are vegetables included in the price. Diners have to pay extra for these, and celery is not included.

Continue reading

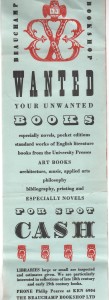

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.

Beauchamp Bookshop of 15a Harrington Road, which was once located by South Kensington station in SW London. Its most striking quality is the boldness of the two colours ( red and black) used for the various period typefaces on display. To someone who grew up in the Swinging Sixties, when designers took inspiration from Victorian (and even older) typefaces and decorative flourishes, it could date from that time. However, the telephone number featured (KEN 6904) might quite equally suggest a slightly earlier date, though the fact that the all-number system began in London in 1966 doesn’t help us much. Some specialist magazines devoted to design, such as Signatureand the Penrose Magazine, were experimenting with typefaces in the forties and fifties. Indeed, the fact that the Beauchamp Bookshop wished to buy books on bibliography and printing suggests that the owner, Mr Philip Pearce, had an active interest in book design. It is telling too that his special need to acquire ‘ late 18thand early 19thcentury books ‘ betrayed a fondness for well printed and well designed books from this pioneering era of fine printing.

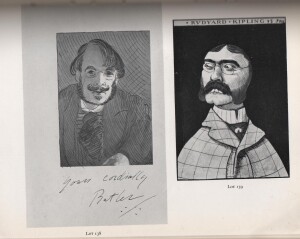

Found at Jot HQ the other day a small scrapbook containing pasted in humorous cuttings from magazines and newspapers that once belonged to the late prankster Jeremy Beadle (1948 – 2008). The date 1897 on the cover was very likely the year in which the compilation was begun, since many of the jokes and anecdotes are clearly of a later date. The high quality of much of the material strongly suggests that the compiler may have been a comedian of some sophistication who was prepared to devote a long period in search of the best gags.

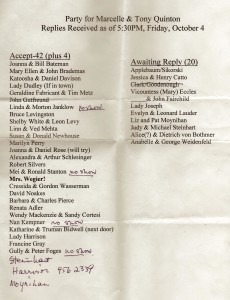

Found at Jot HQ the other day a small scrapbook containing pasted in humorous cuttings from magazines and newspapers that once belonged to the late prankster Jeremy Beadle (1948 – 2008). The date 1897 on the cover was very likely the year in which the compilation was begun, since many of the jokes and anecdotes are clearly of a later date. The high quality of much of the material strongly suggests that the compiler may have been a comedian of some sophistication who was prepared to devote a long period in search of the best gags. Found among papers at Jot HQ ( heaven knows where it came from ) is this printed list of the good and great ( some not so good) who were invited by a friend or friends to attend a party for the philosopher (Lord)

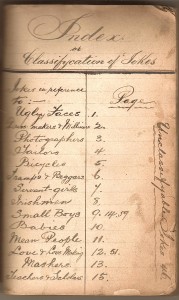

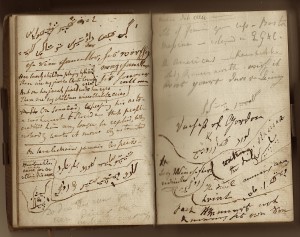

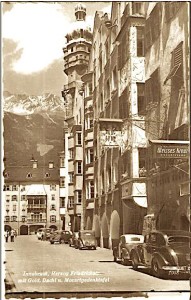

Found among papers at Jot HQ ( heaven knows where it came from ) is this printed list of the good and great ( some not so good) who were invited by a friend or friends to attend a party for the philosopher (Lord)  The front part is a short record of travels in Germany and Belgium in which the anonymous male diarist, who is accompanying his mother, at one point tells us that he was born in 1802, is very scathing about the appearance of most of his travelling companions. In one instance he remarks that the young son of the parson in the party ‘seemed to be as ugly as his father and as vulgar as his cousin’. He is singularly unimpressed by most of the foreigners he encounters along the way. For instance, he notes that his fellow diners at the Table d’Hote, were ‘12 disgusting looking Germans who luckily eat enormously & spoke little ‘. The following evening diners at the same table were’ rather more disgusting in their appearance & manner of eating than the day before ‘. Predictably, he is also critical of the meals he is obliged to eat and the inns that serve and accommodate him. In one inn he accuses the landlord of serving him a dish of greyhound puppy. Our diarist certainly places himself above the common lot. He seems knowledgeable about art and is a little snooty regarding the collections he views, suspecting that most of the paintings were copies from the masters. More positively, he is often ecstatic about the scenery and buildings he encounters and he particularly praises cathedrals and castles. We yearn for more, but unfortunately, the diary stops abruptly after thirty pages.

The front part is a short record of travels in Germany and Belgium in which the anonymous male diarist, who is accompanying his mother, at one point tells us that he was born in 1802, is very scathing about the appearance of most of his travelling companions. In one instance he remarks that the young son of the parson in the party ‘seemed to be as ugly as his father and as vulgar as his cousin’. He is singularly unimpressed by most of the foreigners he encounters along the way. For instance, he notes that his fellow diners at the Table d’Hote, were ‘12 disgusting looking Germans who luckily eat enormously & spoke little ‘. The following evening diners at the same table were’ rather more disgusting in their appearance & manner of eating than the day before ‘. Predictably, he is also critical of the meals he is obliged to eat and the inns that serve and accommodate him. In one inn he accuses the landlord of serving him a dish of greyhound puppy. Our diarist certainly places himself above the common lot. He seems knowledgeable about art and is a little snooty regarding the collections he views, suspecting that most of the paintings were copies from the masters. More positively, he is often ecstatic about the scenery and buildings he encounters and he particularly praises cathedrals and castles. We yearn for more, but unfortunately, the diary stops abruptly after thirty pages.

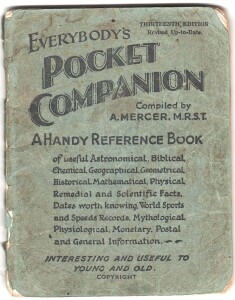

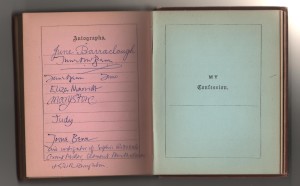

Most of the Common-Place books you find in auctions or second-hand bookshops date from the nineteenth century—usually before about 1860—and are dull, dull, dull! They invariably contain passages from history books, books of sermons, and extracts from poems by Felicia Hemans and Robert Southey. Often they are illustrated by amateurs who like to think they can draw. Occasionally there are exceptions to this rule, but these rarely surface. So it’s nice in this Age of the Internet to find a Common –Place book that contains some information that is not always easy to find using Google. Such is the volume that we at Jot HQ discovered in a box of ephemera the other day.

Most of the Common-Place books you find in auctions or second-hand bookshops date from the nineteenth century—usually before about 1860—and are dull, dull, dull! They invariably contain passages from history books, books of sermons, and extracts from poems by Felicia Hemans and Robert Southey. Often they are illustrated by amateurs who like to think they can draw. Occasionally there are exceptions to this rule, but these rarely surface. So it’s nice in this Age of the Internet to find a Common –Place book that contains some information that is not always easy to find using Google. Such is the volume that we at Jot HQ discovered in a box of ephemera the other day.