|

| Joan Fontaine in 'Rebecca' |

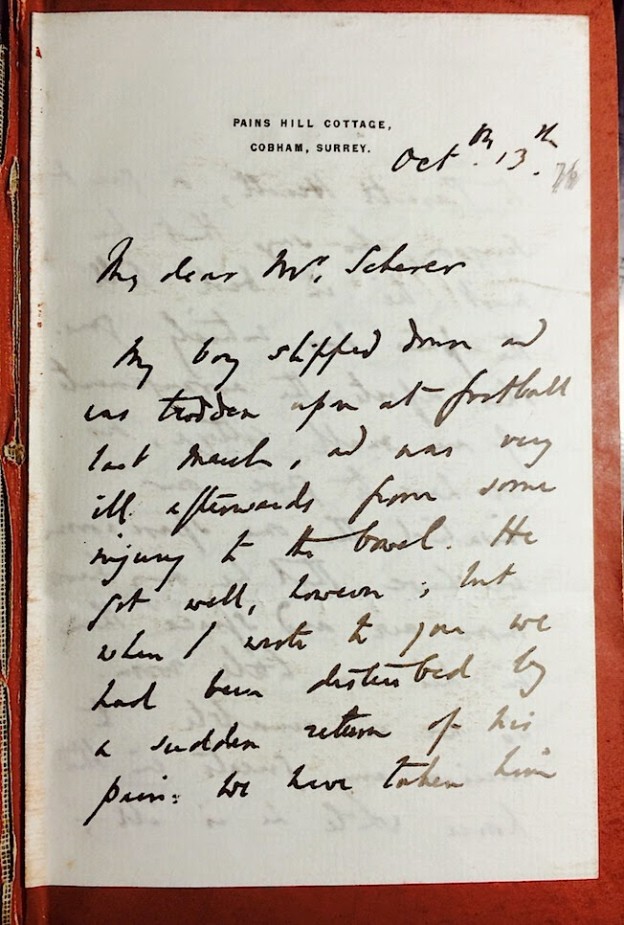

Found in The Fingerpost: A Guide to Professions for Educated Women, with Information as to Necessary Training (Central Bureau for the Employment of Women,1906) an article about getting work as a female companion. It suggests that the occupation, often found in thrillers and novels up to the late 1930s, hardly existed even in 1906. Vere Cochran, the writer of this piece, says that the profession was at its height in early Victorian times when 'semi invalidism' was a prevailing fashion. 'Who (now) can afford the doubtful luxury of a paid companion?' One of the most notable companions in fiction is the unnamed narrator of Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938) While working as the companion to a wealthy American woman on holiday in Monte Carlo she meets the rich and troubled widower Max de Winter who whisks her off to his country mansion Manderley...

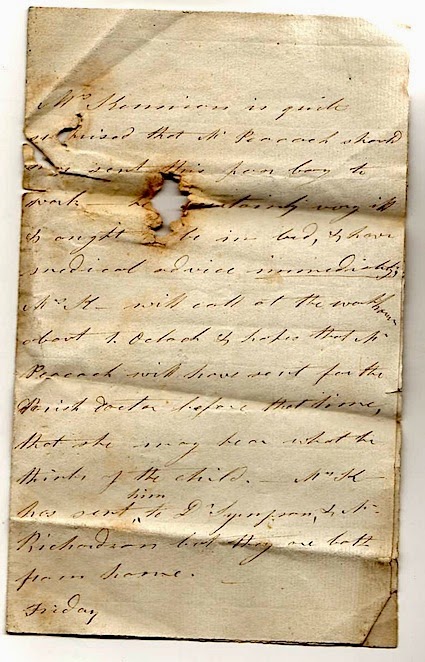

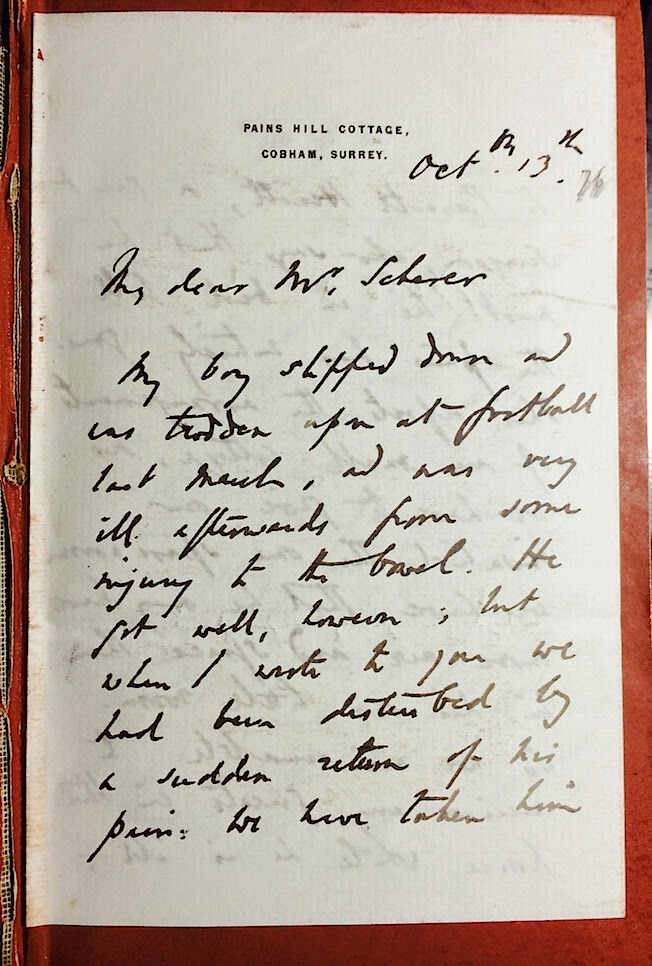

"Companion, Housekeeper, or any position of trust - I could undertake work of this kind".

If the many seekers after work who open their campaign with these words could gauge their true import, or the effect which they produce, they would not so lightly use them. Few words could more clearly display their ignorance with regard to the conditions of the labour market;indeed, to the ears of those who know and who receive year by year hundreds of such applications, these words almost constitute a badge of incapacity.