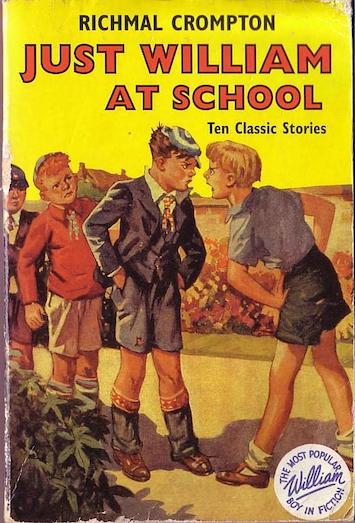

Today, when fully formed adults from around the world queue patiently at the portal to Platform 9 ¾ at King’s Cross Station to have their photograph taken beside the Harry Potter luggage trolley, it’s worth reading another and better children’s writer, the one-time Classics teacher and creator of William, Richmal Crompton, as she explains in an article in the October 1952 issue of The Writer, how she began her career as a writer for adults.

‘I submitted the first one to a women’s magazine and the editor, accepting it, asked for another story about children. I remember that I racked my brains, trying to invent a different set of children from the ones I had already used, and it was with a feeling of guilt and inadequacy that I finally fell back again on the children of the first story. Asked for a third story about children, I wrestled once more with the temptation to use the same set of children, succumbing to it finally with the same sense of guilt. When I had written the fifth story I said to myself: “This must stop. You must find a completely different set of children for the next story.” But somehow I didn’t and gradually the ‘William’ books evolved. They were still, however, regarded as books for adult reading, and I think it was not till the last war that they found their way from the general shelves to the children’s department in the bookshops. And even now I receive letters from adult—even elderly –readers…

…if you are writing about children for children, you must be able to see the world around you as a child sees it. To “ write down” for children is an insult that a child is quick to perceive and resent. Children enjoy assimilating new facts and ideas, but only if the writer is willing to rediscover these facts and ideas with the children, not if he hands out information from the heights of adult superiority. I think the fact that the ‘William’ stories wer4e originally with no eye on a child-reading public has helped to make them popular with children…The plots are not specially devised for children, but I think that if there’s anything I the story that children don’t understand they just don’t worry about it. Children, too, seem to like a series of stories dealing with the same character—especially if it’s a character with which the normal child can identify itself…

In those early days I saw myself as a budding novelist and wrote the William stories —rather carelessly and hurriedly—as pot-boilers. The history of the pot-boiler, by the way, is an interesting one. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Hans Andersen’s fairy tales, Stevenson’s Treasure Island were all written as pot-boilers…Stevenson would have been surprised to know that after his death the story that people connected most readily with his name would be Treasure Island…

Continue reading

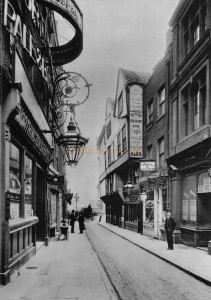

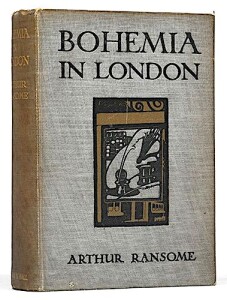

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually. in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

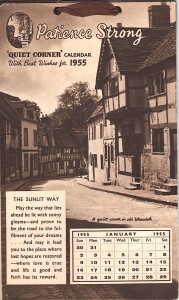

Found amongst a pile of books at Jot HQ, the pocket-sized ‘Patience Strong ‘Quiet Corner ‘calendar for 1955 with its sepia photographs of ‘ picturesque ‘ spots in England. We had almost forgotten that publishers still used sepia photographs as late as this, but then remembered the lifeless and dispiriting photographs of landscapes and empty streets in Arthur Mee’s ‘King’s England’ series of county guide books. No wonder the county guides published by Shell from 1934 were regarded as such a welcome change from these dreary volumes. Mee’s totally predictable descriptions of towns and villages in each county were matched by Strong’s trite and cliché-ridden verse formatted as prose in her calendar and exemplified in ‘ The Sunlit Way ‘which accompanied a traffic-free photo of a ‘ quiet corner of old Warwick ‘ on the page for January 1955.

Found amongst a pile of books at Jot HQ, the pocket-sized ‘Patience Strong ‘Quiet Corner ‘calendar for 1955 with its sepia photographs of ‘ picturesque ‘ spots in England. We had almost forgotten that publishers still used sepia photographs as late as this, but then remembered the lifeless and dispiriting photographs of landscapes and empty streets in Arthur Mee’s ‘King’s England’ series of county guide books. No wonder the county guides published by Shell from 1934 were regarded as such a welcome change from these dreary volumes. Mee’s totally predictable descriptions of towns and villages in each county were matched by Strong’s trite and cliché-ridden verse formatted as prose in her calendar and exemplified in ‘ The Sunlit Way ‘which accompanied a traffic-free photo of a ‘ quiet corner of old Warwick ‘ on the page for January 1955.

We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner.

We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner.