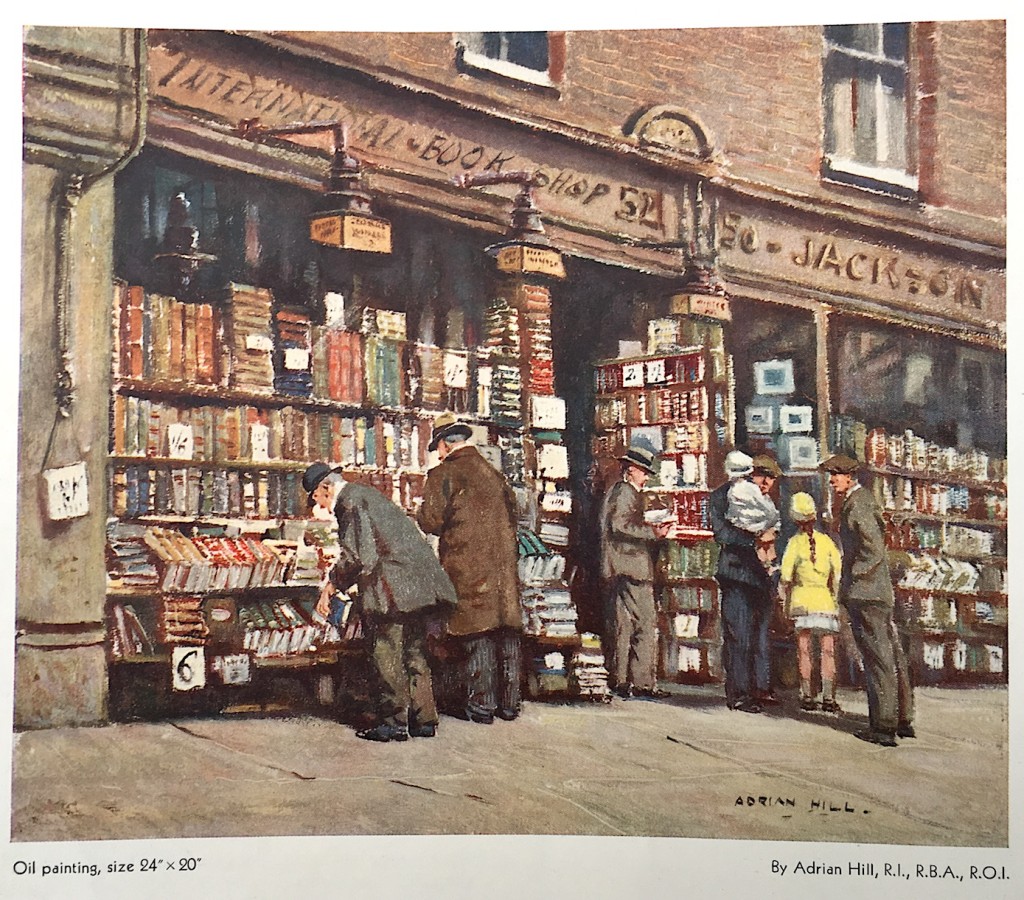

Edward Baker, a bookseller from John Bright Street, Birmingham, frequently placed full page adverts in the Bookman magazine during the early years of the twentieth century. In previous jots we have looked at deleted items that a hundred or more years later were listed in Abebooks with large ( sometimes eye-watering )prices attached to them. This time we feature a selection of ‘ first and scarce editions ‘ taken from an advert of October 1913. Current Abebook prices are listed next to them. All books are first editions unless otherwise stated.

Edward Baker, a bookseller from John Bright Street, Birmingham, frequently placed full page adverts in the Bookman magazine during the early years of the twentieth century. In previous jots we have looked at deleted items that a hundred or more years later were listed in Abebooks with large ( sometimes eye-watering )prices attached to them. This time we feature a selection of ‘ first and scarce editions ‘ taken from an advert of October 1913. Current Abebook prices are listed next to them. All books are first editions unless otherwise stated.

Oliver Goldsmith, Vicar of Wakefield, 2 vols 1766. £4 4s (£4 20p)

Today @ £4,000 – £5,000

Rudyard Kipling, Plain Tales from the Hills, £6 6s (£6 30p)

Today @ £695.

Rudyard Kipling, Soldiers Three, 1888, £8 8s (£8 40p)

Today @ £2,800

Lord Alfred Douglas, City of the Soul, 1899. 15s (75p)

Today @ £488.

Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylvarum, fo., 1627. £6 6s (£6 30p)

Today a 1635 ed. @ £325

The Scourge, with 18 coloured plates by Cruikshank, 2 vols.,1811 -12. £3 3s (£3 60p)

Today 11 volumes @ £7,500

Southey & Coleridge, St Joan, 2nd ed inscribed, 1798. £21

Today same ed. inscribed to Chas. Lamb @ £4,800

Thos. Hughes, Tom Brown at Oxford, 1859. £6 6s (£6 30p)

Today @ £395

Capt. Dickinson, Narrative of the Operations for the Recovery of the Public Stores and Treasure Sunk in H.M.S. “Thetis“, 1836. Very rare. 10s 6d ( 52p)

Today this guide to the whereabouts of sunken treasure is yours for £500 !

Lady Caroline Lamb, Glenarvon, 1816. £7 10s (£7 50p)

Today this ‘mad, bad, and difficult to read ‘novel is yours for a mere £1,250. Continue reading

others.

others.

Found in a copy of John O’London’s Weekly for 18th April 1952 is a review of Collector’s Progress by Wilmarth Lewis ( 1895 – 1979) in which the author reveals that the combination of wealth and a collector’s obsession brought about the greatest collection of manuscripts relating to Horace Walpole in the world.

Found in a copy of John O’London’s Weekly for 18th April 1952 is a review of Collector’s Progress by Wilmarth Lewis ( 1895 – 1979) in which the author reveals that the combination of wealth and a collector’s obsession brought about the greatest collection of manuscripts relating to Horace Walpole in the world.

Found in a thriller by

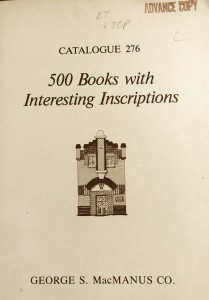

Found in a thriller by  Found – a 1982 book collector’s catalogue from George S Macmanus of Philadelphia 500 Books with Interesting Inscriptions. Mostly modern American and British literature, it has many direct signed presentation from the authors and many

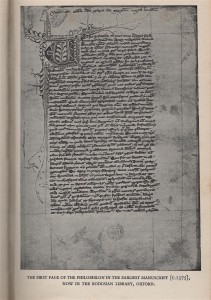

Found – a 1982 book collector’s catalogue from George S Macmanus of Philadelphia 500 Books with Interesting Inscriptions. Mostly modern American and British literature, it has many direct signed presentation from the authors and many  Bishop Bury of Durham spent so much money on books that he lived in dire poverty and debt and when he died all that could be found to cover his corpse was some underwear belonging to his servant.

Bishop Bury of Durham spent so much money on books that he lived in dire poverty and debt and when he died all that could be found to cover his corpse was some underwear belonging to his servant.