Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Found in the Summer 1924 issue of Now & Then (Jonathan Cape) is this brief announcement:

‘LUMMOX finds new admirers every day. Miss Hurst is expected in England shortly, and many admirers are hoping to meet her. She is a prominent figure in New York literary and dramatic circles and has a number of friends in Europe also. The ‘ ban ‘ of the circulating library still remains, but the book is on sale at the bookshops. The current impression is the third.’

This ‘ban’ is a bit of a puzzle. The journalist for Now & Then places the word in quotation marks, which suggests that although Mrs Hurst’s book was in the shops, it was not available for borrowing in certain circulating libraries, though these libraries are not specified. Nor is it clear whether these libraries are in the U.S. or the U.K. A thorough online trawl has revealed nothing on this issue.

At the time Fannie ( or Frances ) Hurst, as the report suggests, was an immensely popular, best-selling American author of rather sentimental and melodramatic novels, many of which had been adapted for the cinema. It has been claimed that she accepted $1m for the film rights of one particular novel. As for the problematical Lummox there seems little in this tale of a young female immigrant who is exploited and abused by her rich employers that could possibly offend even the most delicate sensibilities of an average circulating library subscriber. However, Hurst’s proto-feminism and support for the oppressed in society might have touched a few nerves among members of the wealthy middle class in post-war Britain. [RR]

Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).

Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).

Few American publishers can boast that they have printed 300 hundred million books. Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (1889 – 1951), however, was one who could. An atheist and socialist who believed that the average American had a right to own a library of enlightening, useful and entertaining texts for a few cents a volume, Haldeman-Julius established the Little Blue Book series in the 1920s. Pocket-sized and ranging in subject matter from ancient culture and classic literature to self-help books and handbooks on making your own candy, the Little Blue Books sold in their millions each year, figured in the early education of such American writers as Saul Bellow and Studs Terkel, and anticipated in some respects the very popular ‘Dummies’ of today, though they were very much cheaper.

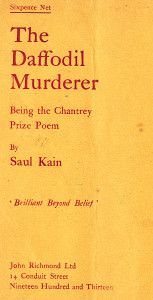

Few American publishers can boast that they have printed 300 hundred million books. Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (1889 – 1951), however, was one who could. An atheist and socialist who believed that the average American had a right to own a library of enlightening, useful and entertaining texts for a few cents a volume, Haldeman-Julius established the Little Blue Book series in the 1920s. Pocket-sized and ranging in subject matter from ancient culture and classic literature to self-help books and handbooks on making your own candy, the Little Blue Books sold in their millions each year, figured in the early education of such American writers as Saul Bellow and Studs Terkel, and anticipated in some respects the very popular ‘Dummies’ of today, though they were very much cheaper. Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

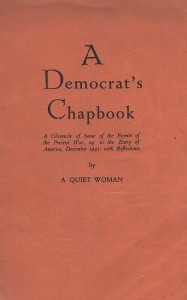

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

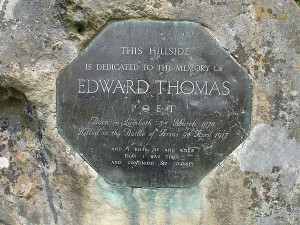

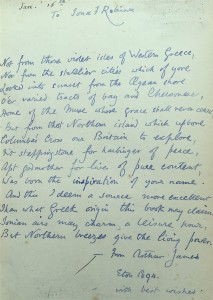

Found among the papers of Joan Stevens (1933-2015) the feminist bookseller and expert on the Powys Brothers and Edward Thomas this piece, apparently unpublished, by

Found among the papers of Joan Stevens (1933-2015) the feminist bookseller and expert on the Powys Brothers and Edward Thomas this piece, apparently unpublished, by

This was sent by

This was sent by