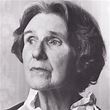

Stella Gibbons, author of Cold Comfort Farm (1932), the cult satire on the doomy English novels of, amongst others, Mary Webb and Sheila Kaye-Smith, seems to have been a very generous and good natured woman, according to her nephew and biographer Reggie Oliver (b1952), who was also a playwright and the author of horror stories. In three pages of a typescript found at Jot HQ, which he sent to the bookseller Joan Stevens (and which may subsequently have been incorporated into his biography, Out of the Woodshed), Gibbons met some colourful characters at the mid- seventies parties she held at her home in Oakshott Avenue, Highgate, which incidentally was a two minute walk from my late uncle, Denis Healey.

Stella Gibbons, author of Cold Comfort Farm (1932), the cult satire on the doomy English novels of, amongst others, Mary Webb and Sheila Kaye-Smith, seems to have been a very generous and good natured woman, according to her nephew and biographer Reggie Oliver (b1952), who was also a playwright and the author of horror stories. In three pages of a typescript found at Jot HQ, which he sent to the bookseller Joan Stevens (and which may subsequently have been incorporated into his biography, Out of the Woodshed), Gibbons met some colourful characters at the mid- seventies parties she held at her home in Oakshott Avenue, Highgate, which incidentally was a two minute walk from my late uncle, Denis Healey.

One was the then fashionable (now almost totally forgotten) novelist John Braine, the former librarian who found fame and fortune with such blockbusters as Room at the Top and The Vodi. Here is Reggie’s description of the man:

‘ He was large, shaggy, genial and physically repulsive. A distinctive presence, enhanced by an unusually loud voice, allowed him to dominate the conversation. I got the impression he was one of those writers—by no means uncommon—whose interest in literature was confined to that produced by themselves. Certainly, I never heard him discuss any books but his own, and even those rarely. But he had pronounced views on almost everything else; and I can remember one enjoyable afternoon when he laid down strict guidelines for us all on the correct method of making bread. Continue reading

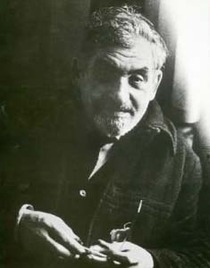

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

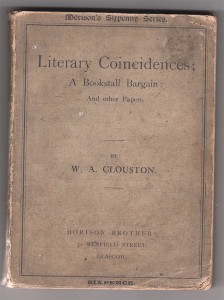

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

In the fascinating Thousand Ways to Earn a Living (1888) the section on ‘Literary Work’ covers journalism, authorship, and something called ‘compilation’. In the journalism chapter modern-day readers might be surprised at the high rates of pay awarded to humble London hacks ( up to £10 a week in 1888—more than a skilled surgeon or a junior barrister might earn ), but few could argue that in late Victorian Britain , as in 2017, in the newspaper world ‘ the majority of new ventures are promoted by newspaper men who have been underpaid or unfairly dealt with by their employers ‘.

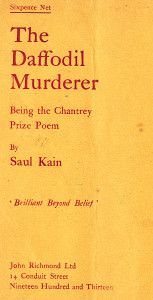

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

Found – a rather battered copy of Siegfried Sassoon’s early book The Daffodil Murderer (1913) published under the pseudonym ‘Saul Kain.’ In decent condition it has auction records like this from Bloomsbury Book Auctions in April 2009:

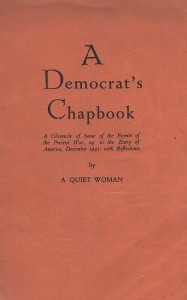

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

The identity of the ‘ quiet woman‘ who wrote A Democrat’s Chapbook (1942), a hundred page long commentary in free verse on the events of the Second World War up to the time when America joined the Allied forces, was only revealed when Anne Powell included two passages from it in her anthology of female war poetry, Shadows of War (1999 ). However, those who had read her volume of Georgian verse entitled Songs from the Sussex Downs ( 1915), a copy of which was found in the collection of Wilfred Owen, might have recognised the style as that of ‘Peggy Whitehouse’, whose Mary By the Sea also appeared under this name in 1946. All three books were the work of Mrs Frances Mundy –Castle (1875 – 1959).

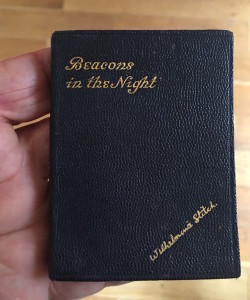

Found a fine copy of Beacons in the Night (Methuen, 1934) by Wilhelmina Stitch. A small book of simple, unsophisticated poetry. Wilhelmina Stitch achieved some popularity and sales in the first half of the 20th century. As a sentimental poet she was very much the Donovan to Patience Strong’s Dylan. She has no Wikipedia page unlike Ms Strong who has a lengthy and well tended entry. Some facts of her life are known and she turns up on a site

Found a fine copy of Beacons in the Night (Methuen, 1934) by Wilhelmina Stitch. A small book of simple, unsophisticated poetry. Wilhelmina Stitch achieved some popularity and sales in the first half of the 20th century. As a sentimental poet she was very much the Donovan to Patience Strong’s Dylan. She has no Wikipedia page unlike Ms Strong who has a lengthy and well tended entry. Some facts of her life are known and she turns up on a site

Found- in a copy of Nip in the Air (John Murray 1974) a book of poems by John Betjeman this affectionate parody by the esteemed travel writer Patrick (‘Paddy’) Leigh Fermor. It is probably from a magazine (pp 379-380), possibly The London Magazine but is not archived anywhere online. It is probably from the 1970s. It deserves a place in a completist Betjeman collection and in any future collection of

Found- in a copy of Nip in the Air (John Murray 1974) a book of poems by John Betjeman this affectionate parody by the esteemed travel writer Patrick (‘Paddy’) Leigh Fermor. It is probably from a magazine (pp 379-380), possibly The London Magazine but is not archived anywhere online. It is probably from the 1970s. It deserves a place in a completist Betjeman collection and in any future collection of  I see him at night with his head low down

I see him at night with his head low down

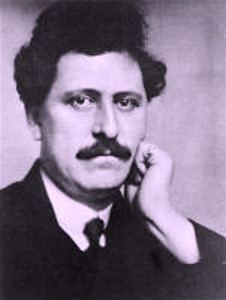

Found in a copy of the literary periodical Today for August 1919 is this advice for aspiring authors from its editor, Holbrook Jackson (pictured):

Found in a copy of the literary periodical Today for August 1919 is this advice for aspiring authors from its editor, Holbrook Jackson (pictured):