There are now no popular magazines in the UK covering the field of rare and antiquarian books. Just seven years ago there were two—Rare Book Review and Book and Magazine Collector –and I wrote regularly for both of them. First to fold was Rare Book Review, a very glossy and well designed affair financed by a wealthy dealer. Previously this had been known for many years as the Antiquarian Book Review, and before this as the clumsily-titled Antiquarian Book Monthly Review, an early issue of which we have here.

When we consider how well designed and glossily produced magazines covering other fields in the arts –such as fashion and the fine arts—it is astonishing how unglamorous this particular magazine must have appeared to the eye of someone familiar with, say, Vogue, the Burlington Magazine, or Country Life at that time. To arrive at something that could compete in visual terms with these titles it took over 40 years and oodles of dealer's dough. It isn’t as if there had never been glossies that had dealt with aspects of the antiquarian book trade---The Bookman, a product of the twenties and thirties, being the most notable.

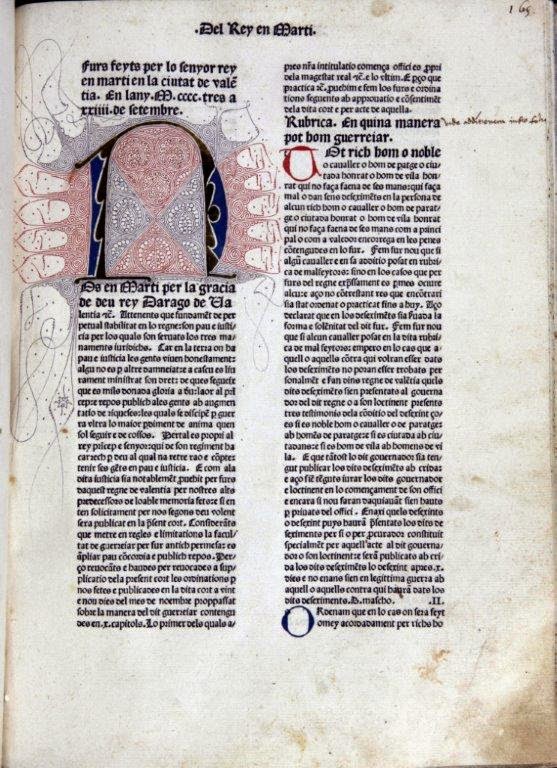

The idea for a new popular magazine distinct from the academic Book Collector and the dryasdust Clique, which was then just a list of books for sale and wanted ( it has since extended its range and appeal) came from the antiquarian book dealer, Paul Minet, who operated from Chicheley House, Bedfordshire. Minet ( 1937 – 2012) provided most of the copy, as he was to do for many years after, but the editing was left to one of his employees, the recently married Elke Sadeghi, then in her early twenties, who was also helping to compile his catalogue of Chicheleana, and was working from Minet’s home and her own flat in the Georgian Brayfield House, near Olney. A local printing firm called Comersgate, based in Newport Pagnell, was chosen and the first issue appeared early in 1974. It is easy to forget that before the advent of digital publishing, which now makes it possible for amateurs to produce magazines and booklets of a professional standard for next to nothing, that back in the seventies a magazine produced cheaply on bog-standard paper by a non-professional art editor would tend to look like this 1974 issue of Antiquarian Book Monthly Review, with its yucky light orange cover, title in Gothic script, and clunky page set-up.

The content was unpromising too, consisting mainly of an exhibition review, some book chat, extensive book lists and a piece on recent science fiction that clearly has nothing to do with ‘antiquarian’ books. There was nothing to suggest that this venture would come to anything. We know that it did, and its eventual success seems to have had something to do with the good intentions of dedicated people like Minet, Sadeghi and her successors as editors, but perhaps more importantly, with the goodwill shown in the letters page, which is dominated by messages of encouragement from dealers and collectors alike, who clearly welcomed what the new enterprise represented.

Sadeghi was eventually replaced as editor and left publishing to start a family with her husband, Dr Majid Sadeghi , who became an internationally acclaimed expert on automotive design and anti-crash impact technology at Cranwell. Around 2002 she became a bookbinder and still practices her art from North Crawley, near Newport Pagnell.

Collectors and dealers now hope that Rare Book Review, the splendid child of Antiquarian Book Monthly Review, will somehow, with the help of another wealthy sponsor, be resurrected.

[R.M.Healey]