Arthur Cravan–poet, traveller, boxer, charlatan and possible forger published the proto-Dadaist magazine ‘Maintenant’ in Paris beteween 1912 and 1915. The 5 issues are now very scarce and can command over a thousand dollars each. The market for them is probably slim and collectors of this material tend not to have deep purses but the mystery of his life and death is still pretty potent..

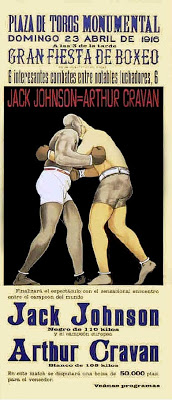

.He was in the news in 2007 when someone turned up at the New York ABAA book fair with a bunch of Oscar Wilde manuscripts of intense value (if they had been right.) They were pronounced forgeries, and Cravan (or Fabian Lloyd as he was born) was mentioned as the possible source and maker of the fakes. Cravan was actually the son of Wilde’s brother in law and was born in Lausanne in 1887. He grew to 6 foot 6 inches and weighed 18 stone. At one point he became the boxing champion of Europe and even fought the World Champion Jack Johnson (poster above) in a rigged fight in Barcelona to get enough money to travel to New York to avoid the military call-up. A relentless world traveller, he wrote “I have twenty countries in my memory and trail in my soul the colors of one hundred cities.” He also wrote in Maintenant that “Every great artist has the sense of provocation” –the key to his style.

I was reminded of Cravan recently on hearing of the death of another poet and boxer Vernon Scannell. How many other boxers wrote poetry? Muhammad Ali made a pretty good fist of it (as it were) Roy Campbell was something of a bruiser, T.E. Hulme fought Wyndham Lewis in Soho Square, Marlowe died in a pub brawl – possibly there are more. With Cravan all you can collect are the five issues of Maintenant and two or three boxing posters, the one to the left can be bought in ‘limited edition’ facsimile for £200. The originals have got to be well into four figures sterling. Continue reading

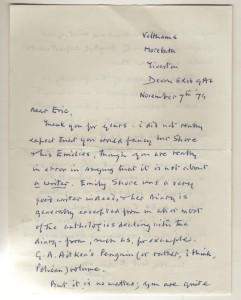

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University.

Gleaned from the archive of the publishers Joan and Eric Stevens are two letters to Eric from the novelist and biographer Oliver Stonor, aka Morchard Bishop (1903 – 1987), from his home in Morebath, on the Devon-Somerset border. The first letter, dated November 1979, mostly concerns the worth of the diarist Emily Shore, who Eric doesn’t consider a ‘ writer ‘, but who is stoutly defended by Stonor as being ‘ a very good writer indeed ‘. Stonor, however, does share Eric’s opinion that ‘people in University English departments ‘would be unlikely to know about her. Stonor also feels that the academic study of English is ‘an activity which can happily be carried out without the intervention of pastors and masters ‘. Stonor, it should be noted, did not attend University. If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

If you fancied a change of scene during WW2 there were problems that needed to be considered if you chose to stay in a hotel or B & B. In his wartime edition of Let’s Halt Awhile(1942) ‘ Ashley Courtenay ‘ offered this advice to the holidaymaker.

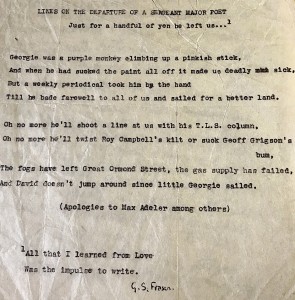

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

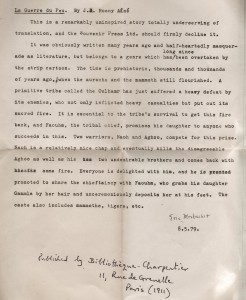

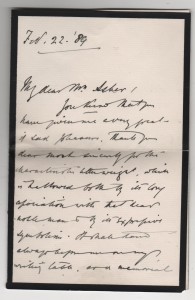

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

La Guerre du Feu, an early fantasy novel, probably written by Joseph Henri Honore Boex (1856 – 1940), one of two Belgian brothers who often wrote fiction together under the pseudonym J.H Rosny-Aine. was published in 1911 by the Bibliotheque-Charpentier in Paris. It is said to have been first translated into English by Harold Talbott in 1967. If this is true, it is odd that the acclaimed journalist and translator Eric Mosbacher in his note of 8.5.1979 ( shown) stated that this ‘ remarkably uninspired story’ was ‘ totally undeserving of translation ‘ and that the Souvenir Press should decline it. It is possible, of course, that a translation into a language other than English was proposed. Mosbacher translated from French, Italian and German.

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).

Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).