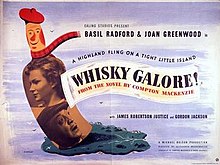

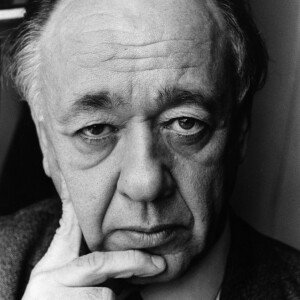

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.

Mackenzie begins his account by declaring that due to the loss of one eye, he may soon face the possibility of having to dictate his words, something he dislikes. For the moment, however, he still writes ‘every word’. He then reveals some surprises:

‘ I wake about noon…drink a cup of coffee and read my letters…I answer about 4,000 a year, which if you figure it out, means at least six weeks of eight-hour days. Too much! After the letters come the papers, but there’s not a great deal on which to waste time there. I get up about one, and if it’s fine take a stroll round the orchard with a glass of milk at the end of it. Then I dictate answers to those letters and with luck settle down by 3 p.m. to work at whatever book I’m writing. I always have to work in chairs because for over forty years I have had to fight with sciatica. A break of a quarter of an hour for tea, and then work goes on until nine, sometimes later. At 9p.m.a very light meal, and then, in a different chair from the one in which I have been writing my book, I write any article or broadcast I have rashly promised to do. Music on gramophone or wireless until midnight, and then sometimes under pressure I work on without music until one or one-thirty. As soon as I’m in bed I enjoy the longed for recreation of doing The Times crossword puzzle. If I do it in under an hour I win: if I’m longer The Times wins. If I’ve failed to finish in an hour The Times is allowed a walk-over and I put the puzzle aside. Then I read until 4 or 5 a.m., sustained by a bar of chocolate and a glass of milk.’

Mackenzie then reveals that he writes using a ‘ very thick Swan pen with a very broad nib ‘ and that he avoids writers’ cramp and developing a large corn on the middle finger by holding the pen ‘ very lightly ‘. He is very particular (one might argue, rather obsessive) about the paper he uses and how he creates the physical book. Continue reading

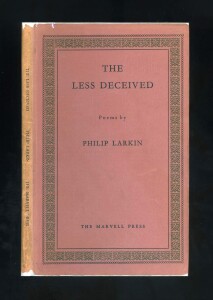

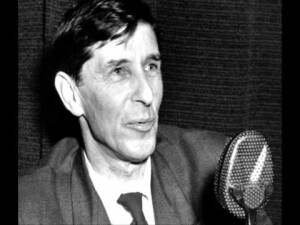

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

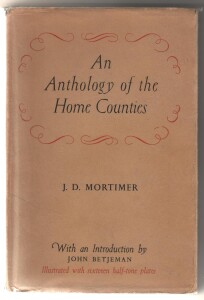

Even today, thirty six years after his death, John Betjeman can still surprise us with his wisdom and original mind. In 1947, less than two years after the end of a war that brought the prospect of a radiation death to the innocent citizens of Great Britain, destroyed some of finest Georgian terraces in London and Bath, that peppered landmark buildings, including St Paul’s Cathedral and the Dulwich Art Gallery with shrapnel, and pock-marked the pastoral landscapes of Surrey, Middlesex and Essex, the editors at Methuen asked the rising poet of the suburbs to provide an Introduction to their new anthology by someone called J. D. Mortimer ( who he?) on the Home Counties.

Even today, thirty six years after his death, John Betjeman can still surprise us with his wisdom and original mind. In 1947, less than two years after the end of a war that brought the prospect of a radiation death to the innocent citizens of Great Britain, destroyed some of finest Georgian terraces in London and Bath, that peppered landmark buildings, including St Paul’s Cathedral and the Dulwich Art Gallery with shrapnel, and pock-marked the pastoral landscapes of Surrey, Middlesex and Essex, the editors at Methuen asked the rising poet of the suburbs to provide an Introduction to their new anthology by someone called J. D. Mortimer ( who he?) on the Home Counties.

Advances

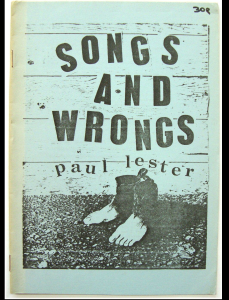

Advances If you search for ‘Paul Lester’ online most the results will concern Paul Lester, the prolific rock critic and biographer; but anyone interested in performance poetry over the past 45 years will hopefully ignore these references and refine their search by adding ‘ poet ‘ or ‘Birmingham’ to ‘ Paul Lester’. They could also add ‘Protean ‘. For ever since Lester published his first poetry pamphlet in 1975 he has been regularly issuing slim volumes ( some very slim) , usually under his own imprint, Protean Publications, from an address in Knowle, near Solihull, although he actually lives in Rubery, in the far south-west edge of Birmingham.

If you search for ‘Paul Lester’ online most the results will concern Paul Lester, the prolific rock critic and biographer; but anyone interested in performance poetry over the past 45 years will hopefully ignore these references and refine their search by adding ‘ poet ‘ or ‘Birmingham’ to ‘ Paul Lester’. They could also add ‘Protean ‘. For ever since Lester published his first poetry pamphlet in 1975 he has been regularly issuing slim volumes ( some very slim) , usually under his own imprint, Protean Publications, from an address in Knowle, near Solihull, although he actually lives in Rubery, in the far south-west edge of Birmingham.