In our first Jot on the artist and cook Scotson-Clark, we referred to the time he spent working in the City just after he had left school. After reading further into his very autobiographical book we now know much more after about this period in his life. It seems that one of his jobs was as a clerk in ‘ a very old-established wine business ‘. He describes the premises with the eye of a painter:

‘ The office was spacious, with large windows. In the winter a comfortable fire burned in the large open grate in the outer office. Green silk curtains screened the lower part of the windows from the vulgar gaze of the passer-by, and corresponding green silk curtains screened the upper part of the desks from the customers or visitors who chanced to call. The ledgers were so large that it was as much as I could do to carry them from the safe to my desk. Quill pens had retired in favour of steel ones on my entry, as had the sand-box in favour of blotting paper. There was no evidence of wine about the place—that would have been vulgar—but the atmosphere was charged with a delicious blend of the sweet aromae of wine, brandy and corks, that came up from the cellar…’

Scotson-Clark then goes on to describe the process of wine-tasting performed by the chief of the business, ‘a most polished gentleman if the old school’.

‘ I have often him with six or seven glasses of wine before him—each glass with a hidden label on the foot, reject four o five on the bouquet alone and then the remaining ones would be tested and arranged in their order of merit before the labels were looked at. And then came the final test of colour. A special old Waterford glass was used for this. It was most beautifully cut, though the lip was as thin as a visiting card. The stem was a trifle dumpy because it had been broken many times and blown together again, and with each repair , so had the stem shrunk. Then there was a special glass for claret, one with an out-turned lip. He liked it because it distributed the bouquet. Now the dock glass you will remember is slightly larger at the bottom than at the top, the alleged object being to concentrate the bouquet so that it escapes just below the nostrils…The glass should be wide enough at the top to admit the nose of moderate proportions, for the bouquet of the vintage is of great importance as the taste.

Champagne should not be taken from a tumbler except as a “corpse reviver” in the forenoon, and at that hour and, for that purpose, an inferior wine is as suitable as a good one, especially if it be “Niblitized”, that is, has incorporated in it a liqueur glass of brandy and a squeeze of lime, with the rind dropped in the glass. Neither the palate nor the stomach is in a fit condition to receive champagne before 8 p.m., and then it should be taken from the thinnest of thin glasses, either of the trumpet or inverted mushroom shape….On principle I am against hollow stems, except as curiosities. Nor do I like coloured glasses, except for hock which is apt to be slightly cloudy

Continue reading

It is in The Last of Spring, one of Rupert Croft-Cooke’s many autobiographical volumes that one finds an account of the author’s experience of renting one of the Cornish bungalows built for writers by the eccentric spiritual medium and author, Mrs A.C. Dawson Scott, in the early 1930s.

It is in The Last of Spring, one of Rupert Croft-Cooke’s many autobiographical volumes that one finds an account of the author’s experience of renting one of the Cornish bungalows built for writers by the eccentric spiritual medium and author, Mrs A.C. Dawson Scott, in the early 1930s.

If Everybody’s Best Friend ( 1939) is to be believed, people were still debating the propriety of men giving up seats to women, whether or not it was necessary to doff a hat to a lady or where a man should walk on a pavement when accompanying a lady, as they had done for centuries before and perhaps still do. On the question of who should pay on a night out, to an earlier generation brought up before the advent of Women’s Liberation, there is no question that a man should pay for everything. Notice that it is tacitly assumed that once the man and woman are married, it is certainly the husband who must pay for a meal and for seats in a theatre or cinema, even though the wife may have an income from her job. But have things changed that much ?

If Everybody’s Best Friend ( 1939) is to be believed, people were still debating the propriety of men giving up seats to women, whether or not it was necessary to doff a hat to a lady or where a man should walk on a pavement when accompanying a lady, as they had done for centuries before and perhaps still do. On the question of who should pay on a night out, to an earlier generation brought up before the advent of Women’s Liberation, there is no question that a man should pay for everything. Notice that it is tacitly assumed that once the man and woman are married, it is certainly the husband who must pay for a meal and for seats in a theatre or cinema, even though the wife may have an income from her job. But have things changed that much ?

In part one we looked at the way John Thaw tried to disguise a leg injury he had sustained as a teenager. Later on in his audition for RADA he had played Richard III with a limp and as Morse he had tried to disguise his limp. But some actors can easily affect a certain gait for dramatic affect. Both Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier maintained that once they had got the walk right the rest of the role fell into place. In an adaptation of Ivy Compton Burnett’s ‘A Family and a Fortune’ Guinness had to leave a room to get out into the cold. The way he flung a scarf round his neck and trod stutteringly before leaving told you everything you needed to know about the climatic conditions and preparing to brave them.

In part one we looked at the way John Thaw tried to disguise a leg injury he had sustained as a teenager. Later on in his audition for RADA he had played Richard III with a limp and as Morse he had tried to disguise his limp. But some actors can easily affect a certain gait for dramatic affect. Both Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier maintained that once they had got the walk right the rest of the role fell into place. In an adaptation of Ivy Compton Burnett’s ‘A Family and a Fortune’ Guinness had to leave a room to get out into the cold. The way he flung a scarf round his neck and trod stutteringly before leaving told you everything you needed to know about the climatic conditions and preparing to brave them.

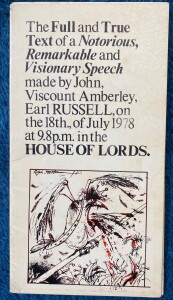

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p. It came from the estate of the Dutch radical Simon Vinkenoog whose birthday (18th July) was the same day as this revolutionary (not to say crazy) speech was given. It has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.

Open Head Press about 1980 at 50p. It came from the estate of the Dutch radical Simon Vinkenoog whose birthday (18th July) was the same day as this revolutionary (not to say crazy) speech was given. It has the full text of Earl Russell’s 1978 maiden speech to the House of Lords.