The best-selling English novelist Barbara Taylor Bradford's early works were mainly about interior decoration and 'homemaking.' They include Decorating to Please Him (How to be the Perfect Wife Series) and Etiquette to Please Him (How to be the Perfect Wife Series). They appeared between 1968 and 1969. BTB's 'perfect wife' paperbacks seem to be aimed at the Stepford Wife archetype and they came out when The Female Eunuch and The Feminine Mystique were on the best seller lists. Nowadays they have a distinct vintage flavour and some dealers even try to get big bucks for them at Amazon. Generally BTB collectable prices for her novels are on the low side, romantic fiction being one of the least collected genres. The Marie Corelli of our age* she is said to be worth £150 million+. Sadly the story about her heating the water in the lake on her estate, so that her pet swans might paddle about in comfort during the winter months, may not be true - BTB says the previous owners of the property had installed it.

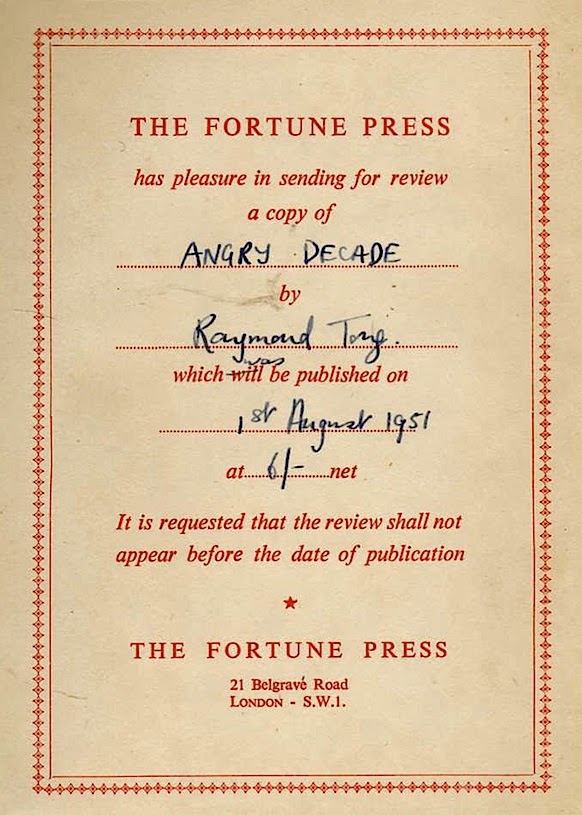

Of course many best selling writers wrote very ordinary, forgotten books before they struck gold - Neil Gaiman's rare and valuable book on the boy band Duran Duran, Arthur Bryant's Unfinished Victory (it showed Nazi sympathies in 1940 -he tried to destroy most copies, hence the book's rarity.) Dan Brown's 187 Men to Avoid: A Survival Guide for the Romantically Frustrated Woman (written with his wife in 1995) and Dean Koontz porn paperback from the 1960s Hung! Not forgetting the great thriller writer Ernest Bramah's 1894 debut English farming and why I turned it up. [Suggested by JK - for which much thanks]

* Her earliest works were of a religious bent like those of Marie Corelli - in 1968 she wrote Children's Stories of the Bible from the Old and New Testaments.